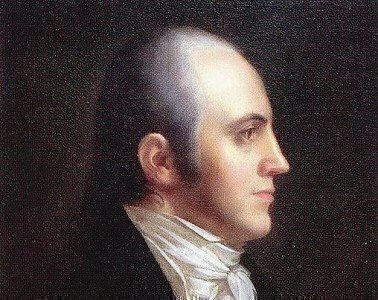

On July 12, 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr faced the prospect of murder charges after shooting Alexander Hamilton the previous day. Why didn’t those charges come to pass and what would happen today in a similar situation?

The issue of presidential immunity from criminal charges while in office received a lot of attention during the Watergate-era investigations into President Richard Nixon during his second term. But Nixon’s first Vice President, Spiro Agnew, also faced potential criminal charges in a separate bribery incident in Maryland in 1973 and also faced the possibility of being charged with a crime while holding office.

The issue of presidential immunity from criminal charges while in office received a lot of attention during the Watergate-era investigations into President Richard Nixon during his second term. But Nixon’s first Vice President, Spiro Agnew, also faced potential criminal charges in a separate bribery incident in Maryland in 1973 and also faced the possibility of being charged with a crime while holding office.

In two separate opinions from that era, the Attorney General’s office spelled out the argument that the President wouldn’t face criminal charges while in office, but he could face charges after leaving office. The President would need to be removed by Congress through the impeachment process or resign to lose that short-term immunity.

However, the Vice President wouldn’t have the same short-term immunity and could face criminal charges while performing his or her constitutional duties. In 2000, Randolph Moss from the Office of Legal Counsel in the Justice Department re-examined those two opinions and still found them to be valid based on “judicial precedents” and the interpretation of Founding-era documents.

Ironically, these documents and other academic writings from the Nixon and Clinton eras refer back to Hamilton and Burr, the two men involved in America’s most famous duel. As you’ll recall, Hamilton, the former Treasury Secretary, and Burr, the sitting Vice President, settled their dispute in a fight that left Hamilton mortally wounded and Burr facing murder charges in New Jersey (where the duel was conducted) and New York (where Hamilton died).

On July 13, 1804, a coroner’s jury started a three-week investigation in New York City to consider murder felony and misdemeanor dueling charges against Vice President Burr. The coroner found enough evidence to indict Burr on both counts. In New Jersey, a grand jury indicted Burr on a murder charge in November 1804. By that time, Burr had left the region to visit his daughter in the South.

Then a constitutional problem came up that required Burr to return to Washington, D.C., right after the New Jersey indictment: He was needed to perform his duties as the presiding officer of the Senate in the impeachment trial of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. Burr served in this important role through the trial and completed his full term as Vice President while under indictment in two states. Eventually, New Jersey dropped its murder charges and Burr was convicted on a dueling misdemeanor charge in New York, under a law championed by Hamilton before his death. Neither state could extradite Burr, and there were conflicting opinions about convictions under anti-dueling statutes.

In 1973, the possibility loomed that President Nixon and Vice President Agnew could face criminal charges at the same time while holding office. In the first opinion of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, Assistant Attorney General Robert Dixon explained how the President’s unique role provided immunity until he left office.

Dixon said a sitting President should be barred by the doctrine of separation of powers from a criminal indictment and trial that would “unduly interfere in a direct or formal sense with the conduct of the Presidency.”

“An impeachment proceeding is the only appropriate way to deal with a President while in office,” Dixon concluded, noting the potential effect on the overall Executive Branch.

The Constitution's Article II, Section 4, spells out that, "The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors."

Two weeks after Dixon’s memo, a second one followed from Solicitor General Robert Bork about the Vice President Agnew’s immunity request from criminal charges while in office. Bork offered a textual explanation about why only the President would enjoy such short-term immunity.

“The President’s immunity rests not only upon the matters just discussed but also upon his unique constitutional position and powers,” Bork wrote. “There are substantial reasons, embedded not only in the constitutional framework but in the exigencies of government, for distinguishing in this regard between the President and all lesser officers including the Vice President.”

Bork then explained the precedent that Vice President Aaron Burr “was subject to simultaneous indictment in two states while in office, yet he continued to exercise his constitutional responsibilities until the expiration of his term.”

In 2000, Moss concluded that while no court has ruled on these immunity issues, “the judicial precedents that bear on the continuing validity of our constitutional analysis are consistent with both the analytic approach taken and the conclusions reached. Our view remains that a sitting President is constitutionally immune from indictment and criminal prosecution.”

He also cited an opinion from Joseph Story in his Commentaries on the Constitution that the President has incidental powers that need to be performed without obstruction and “the President cannot, therefore, be liable to arrest, imprisonment, or detention, while he is in the discharge of the duties of his office.”

In 1998, Yale scholar Akhil Reed Amar also referenced Story’s remarks in Senate testimony that later appeared in a law-review article. Amar said based on his structural interpretation of the Constitution that “other impeachable officers-Vice Presidents, Cabinet officers, judges, and justices - may be indicted while in office. But the Presidency is constitutionally unique - in the President the entirety of the power of a branch of government is vested.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.