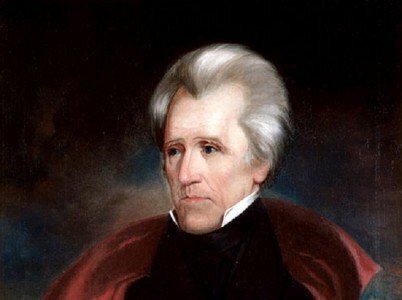

The late President Andrew Jackson is back in the news this week after the current President referenced Jackson’s viewpoints about the North-South conflict that became the Civil War.

In an interview with the Washington Examiner, Donald Trump extolled Jackson’s virtues when it came to conflict resolution.

“I mean, had Andrew Jackson been a little later, you wouldn't have had the Civil War. He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart. And he was really angry that -- he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War. He said, ‘There's no reason for this.’ People don't realize, you know, the Civil War — if you think about it, why? People don't ask that question, but why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?” Trump asked.

“I mean, had Andrew Jackson been a little later, you wouldn't have had the Civil War. He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart. And he was really angry that -- he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War. He said, ‘There's no reason for this.’ People don't realize, you know, the Civil War — if you think about it, why? People don't ask that question, but why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?” Trump asked.

President Trump’s critics were quick to point out that Jackson had died more than 15 years before the Civil War began. But others believe Trump was referencing the various North-South conflicts that were front-burner issues during Jackson’s two terms in the White House.

On Monday night, Trump clarified his remarks via his Twitter account. “President Andrew Jackson, who died 16 years before the Civil War started, saw it coming and was angry. Would never have let it happen!” Trump said.

Among historians and other academics, the Jackson presidency has been studied in detail for a long time. And there are two important events in that era, between 1829 and 1837, that showed Jackson conflicting views on states’ rights, slavery, and North-South relations.

The event most prominently mentioned in coverage about Trump’s remarks is the Nullification Crisis. In 1832, the state of South Carolina, enraged by tariffs placed on trade by the federal government, convened a convention and decided to ignore the congressional acts about the tariffs. The convention proclaimed that the acts were “unauthorized by the Constitution of the United States, and violate the true meaning and intent thereof and are null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this State."

John Calhoun, Jackson’s vice president, was one of the nullification movement’s supporters. In December 1832, President Jackson issued a proclamation that stated the nullification movement was wrong on constitutional grounds.

“I consider, then, the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which It was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed,” Jackson said.

In March 1833, Congress authorized President Jackson to use military force, if needed, to enforce the tariff laws in South Carolina. At the time, Jackson told Lewis Cass that he saw the crisis, in no uncertain terms, as a secession crisis. "If I can judge from the signs of the times Nullification, and secession, or in the language of truth, disunion, is gaining strength, we must be prepared to act with promptness, and crush the monster in its cradle before it matures to manhood,” Jackson wrote.

Henry Clay and others brokered a compromise in Congress that averted a physical showdown between federal troops and the state of South Carolina. After the deal was struck, Jackson wrote to the Rev. A.J. Crawford in May 1833 that the tariff issue was a “pretext” and that the goals of the nullifiers were “disunion and southern confederacy” and “the next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question."

But two years later, President Jackson interceded on the side of the slave-holding states in another controversy about the abolitionist movement. Jackson had also owned slaves for much of his adult life. Northern opponents of slavery had started one of the first-ever direct-mail campaigns in 1835 by sending abolitionist literature through the federal mail system to clergy and public officials.

Jackson and his postmaster general allowed local southern officials to intercept and destroy the literature. The President also asked Congress to pass a “law as will prohibit, under severe penalties, the circulation in the southern States, through the mail, of incendiary publications intended to instigate the slaves to insurrection.” The bill never passed.

In his farewell address, Jackson addressed both of these situations. The outgoing President spoke about sectionalism in blunt terms. “We behold systematic efforts publicly made to sow the seeds of discord between different parts of the United States and to place party divisions directly upon geographical distinctions; to excite the South against the North and the North against the South, and to force into the controversy the most delicate and exciting topics--topics upon which it is impossible that a large portion of the Union can ever speak without strong emotion,” Jackson wrote.

But he also repeated the need to keep the Union solvent at the same time, under one constitutional system of laws. “In order to maintain the Union unimpaired it is absolutely necessary that the laws passed by the constituted authorities should be faithfully executed in every part of the country, and that every good citizen should at all times stand ready to put down, with the combined force of the nation, every attempt at unlawful resistance, under whatever pretext it may be made or whatever shape it may assume,” Jackson pleaded.

However, Jackson also reinforced the concept of state sovereignty and the ability of people within states to control their own destiny. “All efforts on the part of people of other States to cast odium upon their institutions, and all measures calculated to disturb their rights of property or to put in jeopardy their peace and internal tranquility, are in direct opposition to the spirit in which the Union was formed, and must endanger its safety,” Jackson argued.

In 1861, the newly minted President Abraham Lincoln dealt with the secession crisis in South Carolina that President Jackson averted in 1833. According to historian Sean Wilentz, Lincoln looked back at Jackson’s writings about the nullification crisis as a reference point.

“Jackson’s proclamation on nullification was one of the few sources he consulted,” Wilentz said. “And thereafter, Jackson’s precedent was very much on his mind.” But Lincoln also agreed with other concepts supported by Jackson’s opponents.

“The significance of Lincoln’s convergence with certain anti-slavery elements of Jacksonian Democracy, and then with certain of Jackson’s political precedents, should not be exaggerated. Yet neither should the convergence be ignored,” Wilentz concluded, also noting that “some of the Jacksonian spirit resided inside the Lincoln White House.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.