President Donald Trump’s executive order seeking to redefine birthright citizenship has cast a new light on a landmark Supreme Court decision, United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).

The executive order issued on Jan. 20, 2025, does not specifically mention the Wong Kim Ark case, but it disputes the key holding of the majority’s decision holding that, with few exceptions, a person born on the soil of the United States is automatically a citizen.

The executive order issued on Jan. 20, 2025, does not specifically mention the Wong Kim Ark case, but it disputes the key holding of the majority’s decision holding that, with few exceptions, a person born on the soil of the United States is automatically a citizen.

The executive order, however, argues two exclusions not considered under Wong Kim Ark. One exclusion is that a person is not a citizen at birth if their mother “was unlawfully present” in the United States and their father was not “a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident” at the time of their birth.

The other exclusion is that a person is not a citizen at birth even if their mother is lawfully present in the United States on a temporary basis, “such as, but not limited to, visiting the United States under the auspices of the Visa Waiver Program or visiting on a student, work, or tourist visa,” and their father “was not a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of said person’s birth.”

The Wong Kim Ark decision determined that a person born in the United States whose parents were Chinese citizens but lawful permanent U.S. residents became a citizen at birth under the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. The exceptions to birthright citizenship listed under Wong Kim Ark included children of foreign ministers, enemy combatants on American soil, members of Indian tribes, and people on foreign public ships.

The 14th Amendment and Citizenship

The Citizenship Clause is the first sentence of the 14th Amendment, and it reads, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” This part of the amendment directly repudiated the Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which said that African Americans born in the United States were not citizens.

Much of the precedent about this clause is based on the Wong Kim Ark decision.

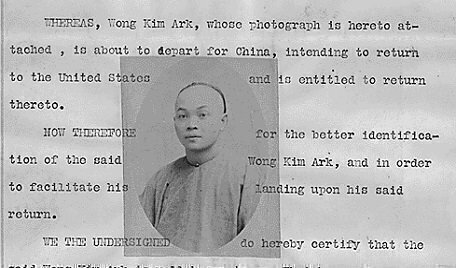

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco, Calif., in 1873 to parents who were both Chinese citizens who resided in the United States at the time and had done so for 20 years. At age 21, he returned to China after a trip and was denied entrance at the port of San Francisco because the customs collector said Wong was not a citizen under the Chinese Exclusion Acts. The District Court of the United States for the Northern District of California ruled in Wong’s favor, and the United States government appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Court, in a 6-2 decision (Justice McKenna took no part in the case), agreed that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen under the 14th Amendment. Justice Horace Gray’s majority opinion stated that Wong Kim Ark, having “a permanent domicil[e] and residence in the United States,” became “at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States,” even though his parents were not United States citizens.

Gray wrote that the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause conformed with British and American common law when it came to people born in the United States as having claims to citizenship, with limited exceptions. These exclusions were limited to “children born of alien enemies in hostile occupation and children of diplomatic representatives of a foreign State,” Gray wrote. These exceptions “by the law of England and by our own law from the time of the first settlement of the English colonies in America, had been recognized exceptions to the fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the country,” he noted. “The principles upon which each of those exceptions rests were long ago distinctly stated by this court.” The other exception, “children of members of the Indian tribes,” was particular to America, “standing in a peculiar relation to the National Government, unknown to the common law.”

Gray also determined that the Chinese Exclusion Acts did not affect Wong’s citizenship status. “The fact, therefore, that acts of Congress or treaties have not permitted Chinese persons born out of this country to become citizens by naturalization, cannot exclude Chinese persons born in this country from the operation of the broad and clear words of the Constitution, ‘All persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.’”

In his dissent, Chief Justice Melville Fuller, joined by Justice John Marshall Harlan, believed the government had the power “notwithstanding the [14th] Amendment, to prescribe that all persons of a particular race, or their children, cannot become citizens.” Fuller stated that the 14th Amendment permitted birthright citizenship if parents “permanently located therein, and who might themselves become citizens; nor, on the other hand, does it arbitrarily make citizens of children born in the United States of parents who, according to the will of their native government and of this Government, are and must remain aliens.”

In recent years, the Court revisited Wong Kim Ark in Plyler v. Doe (1982). In a 5-4 decision, the Court overturned a Texas law allowing the state to withhold funds from local school districts used for educating children of illegal aliens. In his majority opinion, Justice William Brennan cited Wong Kim Ark and a 1912 legal treatise that held there was no difference “between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful.”

Today, arguments contesting a broad interpretation of Wong Kim Ark and birthright citizenship point to several factors. In a filing with the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, the Justice Department states that “the Fourteenth Amendment affords so-called ‘birthright citizenship’ only to those persons born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction—and thus excludes children of noncitizens here illegally as well as children of temporary visaholders.”

The department also cites language in the 1866 Civil Rights Act as supporting the argument that some persons are not under the “jurisdiction of the United States” because of their allegiance to another country. “Ample historical evidence shows that the children of non-resident aliens are subject to foreign powers—and, thus, are not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States and are not constitutionally entitled to birthright citizenship,” the brief argues.

The Justice Department contends the plaintiffs misread the intent of the Wong Kim Ark decision. “Despite some broadly worded dicta, the Court’s opinion thus leaves no serious doubt that its actual holding concerned only children of permanent residents. The [executive order] is fully consistent with that holding.”

On Thursday, a federal judge temporarily blocked the executive order from going into effect, pending a hearing on Feb. 6, 2025.

But in the canon of Supreme Court cases, United States v. Wong Kim Ark remains as a landmark decision that has rarely been contested.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.