Summary

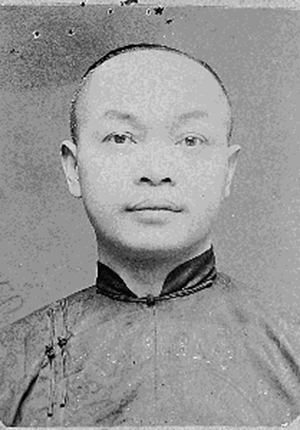

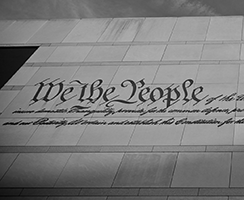

Ratified in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment opens with the Citizenship Clause. It reads, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The Supreme Court addressed the meaning of this key provision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco to parents who were both Chinese citizens. At age 21, he took a trip to China to visit his parents. When he returned to the United States, he was denied entry on the ground that he was not a U.S. citizen. In a 6-to-2 decision, the Court ruled in favor of Wong Kim Ark. Because he was born in the United States and his parents were not “employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China,” the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment automatically made him a U.S. citizen. This case highlighted a disagreement between the Justices over the precise meaning of one key phrase in the Citizenship Clause: “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”