Summary

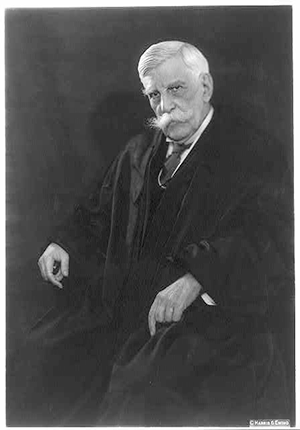

During World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, which made it a crime to convey information intended to interfere with the war effort. The Act made it a crime to convey information intended to interfere with the war effort. In Schenck v. United States, Charles Schenck was charged under the Espionage Act for mailing printed circulars critical of the military draft. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes upheld Schenck’s conviction and ruled that the Espionage Act did not conflict with the First Amendment. In his opinion for the Court, Holmes established the famous “clear and present danger test”—a key reminder that free speech rights are not absolute. However, later that year, Holmes would embrace a bold vision of robust free speech protections in a different case, Abrams v. United States, as would the Supreme Court itself in future decades. Justice Holmes and his colleague, Justice Louis Brandeis, would lead the way with a series of famous free speech opinions over the next decade.