Summary

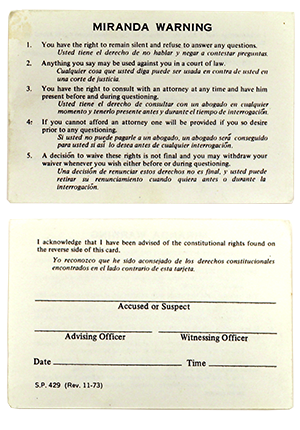

Ernesto Miranda was accused of a serious crime. The police brought Miranda into custody, but they did not inform him of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney. They found a witness and arranged for a lineup of possible suspects. They asked the witness whether she could identify the person who committed the crime. She thought that it might be Miranda, but she was not sure. The police then told Miranda that she had identified him. Miranda confessed to the crime and was ultimately convicted. The Warren Court threw out Miranda’s conviction. Miranda was part of the Warren Court’s revolution in criminal procedure, along with other cases presented here, such as Gideon and Mapp. Miranda required, famously, that those arrested be informed of their rights to remain silent and obtain an attorney under the Fifth Amendment.