Summary

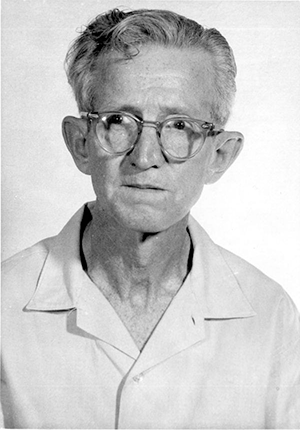

In Johnson v. Zerbst (1938), the Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment’s right to assistance of counsel required the federal government to appoint counsel to an indigent defendant who could not afford one. In Gideon, a much more famous case, the Supreme Court “incorporated” this right against the state government. There, Clarence Earl Gideon was accused of a burglary at a pool hall in Florida, but he could not afford an attorney. As a result, Gideon had to represent himself in court, and he was convicted of the burglary and sentenced to five years in prison. While in prison, Gideon became a “jailhouse” lawyer—studying the Constitution, building his case, and eventually petitioning the Supreme Court to take it up. The Court took Gideon’s case and ruled in his favor—concluding that he did have a right to an attorney. The case was part of the Warren Court’s revolution in criminal procedure, whereby the Court systematically began to interpret constitutional provisions in cases such as Miranda and Mapp more favorably for criminal defendants.