Summary

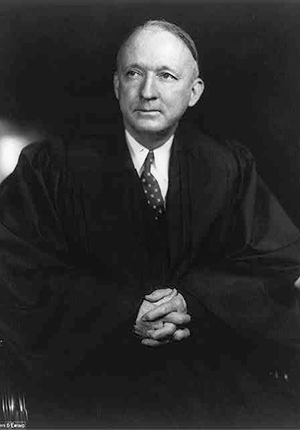

Engel v. Vitale was an important Supreme Court decision policing the boundaries of church and state. There, the New York State Board of Regents authorized public schools to recite a short, voluntary prayer at the beginning of each school day. The prayer read, “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.” A group of parents challenged this government-sponsored prayer, arguing that it violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. The Supreme Court—in a six-to-one decision—agreed with these parents and struck down the New York prayer. In his majority opinion for the Court, Justice Hugo Black concluded that state officials may not compose official state prayers and require that they be recited in public schools, even if the prayer was “denominationally neutral” and students could opt out of reciting it. The Engel decision resulted in a massive public backlash against the Supreme Court, but the Court held its ground and further expanded the reasoning of the school prayer decision in later cases. However, the Court has also upheld public prayers in contexts involving adults, such as legislative sessions and at town council meetings.