Historic Document

Letter to Bernard Moore (ca. 1773)

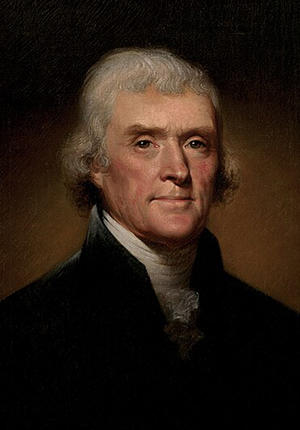

Thomas Jefferson | 1773

Summary

Writing to Henry Lee in 1825, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) said that the Declaration of Independence “was intended to be an expression of the American mind,” resting “on the harmonising sentiments of the day, whether expressed, in conversations, in letters, printed essays or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney Etc.” The reading list excerpted below—drafted roughly three years before Jefferson wrote the Declaration—suggests the Ancient and Enlightenment philosophers that influenced Jefferson the most. Jefferson sent this reading list to Bernard Moore, the son of a friend who was about to study law. Jefferson continued to revise it over the years to guide the education of other young friends who were preparing for college and law school, including his nephew Peter Carr, James Madison, and James Monroe.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Bernard Moore:

‘Th: Jefferson to Bernard Moore.

Before you enter on the study of the law a sufficient ground-work must be laid. for this purpose an acquaintance with the Latin and French languages is absolutely necessary. the former you have; the latter must now be acquired. Mathematics and Natural philosophy are so useful in the most familiar occurrences of life, and are so peculiarly engaging & delightful as would induce every person to wish an acquaintance with them. besides this, the faculties of the mind, like the members of the body, are strengthened & improved by exercise. Mathematical reasonings & deductions are therefore a fine preparation for investigating the abstruse speculations of the law. in these and the analogous branches of science the following elementary books are recommended.

- Mathematics. Bezout, Cours de Mathematiques. the best for a student ever published. Montucla or Bossu’s histoire des Mathematiques.

- Astronomy. Ferguson, and Le Monnier, or de la Lande.

- [Geography. Pinkerton.]

- Nat. Philosophy. Joyce’s Scientific dialogues. Martin’s Philosophia Britannica. Mussenbroek’s Cours de Physique.

This foundation being laid, you may enter regularly on the study of the Law, taking with it such of it’s kindred sciences as will contribute to eminence in it’s attainment. the principal of these are Physics, Ethics, Religion, Natural law, Belles lettres, Criticism, Rhetoric and Oratory. the carrying on several studies at a time is attended with advantage. variety relieves the mind, as well as the eye, palled with too long attention to a single object. but, with both, transitions from one object to another may be so frequent and transitory as to leave no impression. the mean is therefore to be steered, and a competent space of time allotted to each branch of study. again, a great inequality is observable in the vigor of the mind at different periods of the day. it’s powers at these periods should therefore be attended to in marshalling the business of the day. for these reasons I should recommend the following distribution of your time.

Till VIII. aclock in the morning employ yourself in Physical studies, Ethics, Religion, natural and sectarian, and Natural law, reading the following books.

- Agriculture. Dickson’s husbandry of the antients. Tull’s horse-hoeing husbandry. Ld Kaim’s Gentleman farmer. Young’s Rural economy. Hale’s body of husbandry. De-Serres Theatre d’Agriculture.

- Chemistry. Lavoisier. Conversations in Chemistry.

- Anatomy. John and James Bell’s Anatomy.

- Zoology. Abregé du Systeme de Linnée par Gilibert. Manuel d’histoire Naturel par Blumenbach. Buffon, including Montbeillard & La Cepede. Wilson’s American Ornithology.

- Botany. Barton’s elements of Botany. Turton’s Linnaeus. Persoon Synopsis plantarum.

- Ethics. & Natl Religion. Locke’s Essay. Locke’s Conduct of the mind in the search after truth. Stewart’s Philosophy of the human mind. Enfield’s history of Philosophy. Condorcet, Progrès de l’esprit humain. Cicero de officiis. Tusculana. de senectute. somnium Scipionis. Senecae Philosophica. Hutchinson’s Introduction to moral Philosophy. Ld Kaim’s Natural religion. Traité elementaire de Morale et Bonheur. La Sagesse de Charron.

- Religion, sectarian. Bible. New Testament. Commentaries on them by Middleton in his works, and by Priestley in his Corruptions of Christianity, & Early opinions of Christ. Volney’s Ruins. the Sermons of Sterne, Massillon & Bourdaloue.

- Natural law. Vattel Droit des Gens. Reyneval, Institutions du droit de la Nature et des Gens.

From VIII. to XII. read Law. the general course of this reading may be formed on the following grounds. Ld Coke has given us the first view of the whole body of law worthy now of being studied: for so much of the admirable work of Bracton is now obsolete that the student should turn to it occasionally only, when tracing the history of particular portions of the law. Coke’s Institutes are a perfect Digest of the law as it stood in his day. after this, new laws were added by the legislature, and new developements of the old laws by the Judges, until they had become so voluminous as to require a new Digest. this was ably executed by Matthew Bacon, altho’ unfortunately under an Alphabetical, instead of Analytical arrangement of matter. the same process of new laws & new decisions on the old laws going on, called at length for the same operation again, and produced the inimitable Commentaries of Blackstone. In the department of the Chancery, a similar progress has taken place. Ld Kaims has given us the first digest of the principles of that branch of our jurisprudence, more valuable for the arrangement of matter, than for it’s exact conformity with the English decisions. the Reporters from the early times of that branch to that of the same Matthew Bacon are well digested, but alphabetically also in the Abridgment of the Cases in Equity, the 2d volume of which is said to have been done by him. this was followed by a number of able reporters, of which Fonblanque has given us a summary digest by commentaries on the text of the earlier work ascribed to Ballow, entitled ‘a Treatise of equity.’ the course of reading recommended then in these two branches of Law is the following.

|

In reading the Reporters, enter in a Common-place book every case of value, condensed into the narrowest compass possible which will admit of presenting distinctly the principles of the case. this operation is doubly useful, inasmuch as it obliges the student to seek out the pith of the case, and habituates him to a condensation of thought, and to an acquisition of the most valuable of all talents, that of never using two words where one will do. it fixes the case too more indelibly in the mind.

From XII. to I. read Politics.

- Politics general. Locke on government. Sidney on Government.

- Priestley’s First principles of Government. Review of Montesquieu’s Spirit of laws. Anon. De Lolme sur la constitution d’Angleterre. DeBurgh’s Political disquisitions.Hatsell’s Precedents of the H. of Commons. select Parliamy debates of England & Ireland.Chipman’s Sketches of the principles of government. The Federalist.

- Political Economy. Say’s Economie Politique. Malthus on the principles of population.Tracy’s work on Political Economy. now about to be printed. (1814.)

In the Afternoon. read History.

History. Antient. the Greek and Latin originals. select histories from the Universal history. Gibbon’s decline of the Rom. empire. Histoire Ancienne de Millot.

- Modern. Histoire moderne de Millot. Russel’s History of Modern Europe. Robertson’s Charles V.

- English. the original historians. to wit. the Hist. of E. II. by E. F.—Habington’s E. IV. More’s R. III. Ld Bacon’s H. VII. LdHerbert’s H. VIII. Goodwin’s H. VIII. E. VI. Mary. Cambden’s Eliz. & James. Ludlow. McCaulay. Fox. Belsham. Baxter’s History of England. (Hume republicanised & abridged.) Robertson’s Hist. of Scotland.

- American. Robertson’s History of America. Gordon’s History of the independance of the US. Ramsay’s Hist. of the Amer. revolution.

- Burke’s Hist. of Virginia. Continuation of do by Jones & Girardin. nearly ready for the pres

|

From Dark to Bed-time. Belles letters. Criticism. Rhetoric. Oratory. to wit

|

Note, under each of the preceding heads, the books are to be read in the order in which they are named. these by no means constitute the whole of what might be usefully read in each of these branches of science. the mass of excellent works going more into detail is great indeed. but those here noted will enable the student to select for himself such others of detail as may suit his particular views and dispositions. they will give him a respectable, an useful, & satisfactory degree of knolege in these branches, and will themselves form a valuable and sufficient library for a lawyer, who is at the same time a lover of science.’

So far the paper; which I send you, not for it’s merit, for it betrays sufficiently it’s juvenile date; but because you have asked it. your own experience in the more modern practice of the law will enable you to give it more conformity with the present course; and I know you will recieve it kindly with all it’s imperfections, as an evidence of my great respect for your wishes, and of the sentiments of esteem and friendship of which I tender you sincere assurances.

Th: Jefferson

***************************************