Historic Document

Notes on the State of Virginia (1782)

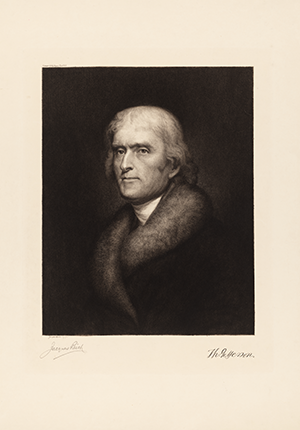

Thomas Jefferson | 1782

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Oswald D. Reich

Summary

Thomas Jefferson, known for drafting the Declaration of Independence, was not present at the Constitutional Convention, or even in the country at the time of its gathering. However, through a searching criticism of Virginia’s own constitution, which had been drafted in the summer of 1776, he did provide his overview of constitutional principles in this text, frequently resorted to by participants in the debates over the Constitution. Jefferson prepared this monograph at the request of the Secretary of the French Legation at Philadelphia. At the center of Jefferson’s view was (what we might call) the half-life of democratic authority, which means that one legislature (or convention) cannot bind a subsequent legislature (or convention).

Selected by

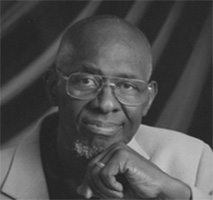

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

QUERY XIII

…

This constitution was formed when we were new and unexperienced in the science of government. It was the first too which was formed in the whole United States….No wonder then that time and trial have discovered very capital defects in it:

1. The majority of the men in the State, who pay and fight for its support, are unrepresented in the Legislature, the roll of freeholders entitled to vote, not including generally the half of those on the roll of the militia, or of the tax gatherers.

2. Among those who share the representation, the shares are very unequal. …

3. The Senate is, by its constitution, too homogeneous with the House of Delegates. Being chosen by the same electors, at the same time, and out of the same subjects, the choice falls of course on men of the same description. The purpose of establishing different houses of legislation is to introduce the influence of different interests or different principles. …

4. All the powers of Government, legislative, executive and judiciary, result to the legislative body. The concentrating these in the same hands is precisely the definition of despotic government… An elective despotism was not the government we fought for, but one which should not only be founded on free principles, but in which the powers of government — should be so divided and balanced among several bodies of magistracy, as that no one could transcend their legal limits without being effectually checked and restrained by the others. For this reason that convention, which passed the ordinance of government, laid its foundation on this basis, that the legislative, executive and judiciary departments should be separate and distinct, so that no person should exercise the powers of more than one of them at the same time. But no barrier was provided between these several powers. …

It is well known, that in July, 1775, a separation from Great Britain, and establishment of Republican Government, had never yet entered into any person’s mind. A convention therefore chosen under that ordinance, cannot be said to have been chosen for purposes which certainly did not exist in the minds of those who passed it. Under this ordinance, at the annual election in April, 1776, a convention for the year was chosen.

Independence, and the establishment of a new form of government, were not even yet the objects of the people at large. One extract from the pamphlet, called Common Sense, had appeared in the Virginia papers in February, and copies of the pamphlet itself had got into a few hands. But the idea had not been opened to the mass of the people in April, much less can it be said that they had made up their minds in its favor. So that the electors of April, 1776, no more than the legislators of July, 1775, not thinking of independence and a permanent Republic, could not mean to vest in these delegates powers of establishing them, or any authorities other than those of the ordinary Legislature.… They could not therefore pass an act transcendent to the powers of other Legislatures. If the present assembly pass any act and declare it shall be irrevocable by subsequent assemblies, the declaration is merely void, and the act repealable, as other acts are... It pretends to no higher authority than the other ordinances of the same session; it does not say that it shall be perpetual; that it shall be unalterable by other Legislatures; that it shall be transcendent above the powers of those who they knew would have equal power with themselves…

Though this opinion seems founded on the first elements of common sense, yet is the contrary maintained by some persons: 1. Because, say they, the conventions were vested with every power necessary to make effectual opposition to Great Britain. But to complete this. Argument, they must go on, and say further, that effectual opposition could not be made to Great Britain without establishing a form of government perpetual and unalterable by the Legislature, which is not true. An opposition which, at some time or other, was to come to an end, could not need a perpetual institution to carry it on; and a government, amendable as its defects should be discovered, was as likely to make effectual resistance, as one which should be unalterably wrong.

2. They urge that if the convention had meant that this instrument should be alterable, as their other ordinances were, they would have called it an ordinance; but they have called it a constitution, which, ex vi termini, means “an act above the power of the ordinary Legislature.”… “Constitutions and ordinances” are used as synonymous. The term constitution has many other significations in physics and in politics; but in jurisprudence, whenever it is applied to any act of the Legislature, it invariably means a statute, law, or ordinance, which is the present case. No inference then of a different meaning can be drawn from the adoption of this title: on the contrary, we might conclude that, by their affixing to it a term synonymous with ordinance, or statute, they meant it to be an ordinance or statute. But of what consequence is their meaning, where their power is denied? If they meant to do more than they had power to do, did this give them power? It is not the name, but the authority, which renders an act obligatory. … To get rid of the magic supposed to be in the word constitution, let us translate it into its definition, as given by those who think it above the power of the law; and let us suppose the convention instead of saying, “We, the ordinary Legislature, establish a constitution,” had said, “We, the ordinary Legislature, establish an act above the power of the ordinary Legislature.’” Does not this expose the absurdity of the attempt?

3. But, say they, the people have acquiesced, and this has given it an authority superior to the laws. It is true, that the people did not rebel against it; and was that a time for the people to rise in rebellion? Should a prudent acquiescence, at a critical time, be construed into a confirmation of every illegal thing done during that period? ... Had an unalterable form of government been meditated, perhaps we should have chosen a different set of people.

There was no cause then for the people to rise in rebellion. But to what dangerous lengths will this argument lead? Did the acquiescence of the colonies, under the various acts of power exercised by Great Britain in our infant state, confirm these acts, and so far invest them with the authority of the people as to render them unalterable, and our present resistance wrong? On every unauthoritative exercise of power by the Legislature, must the people rise in rebellion, or their silence be construed into a surrender of that power to them? If so, how many rebellions should we have had already? ...

The other States in the Union have been of opinion, that to render a form of government unalterable by ordinary acts of assembly, the people must delegate persons with special powers. They have accordingly chosen special conventions to form and fix their governments. The individuals then who maintain the contrary opinion in this country [Virginia] should have the modesty to suppose it possible that they may be wrong, and the rest of America right. But if there be only a possibility of their being wrong, if only a plausible doubt remains of the validity of the ordinance of government, is it not better to remove that doubt, by placing it on a bottom which none will dispute? If they be right, we shall only have the unnecessary trouble of meeting once in convention. If they be wrong, they expose us to the hazard of having no fundamental rights at all. True it is, this is no time for deliberating on forms of government. While an enemy is within our bowels, the first object is to expel him. But when this shall be done, when peace shall be established, and leisure given us for intrenching within good forms, the rights for which we have bled, let no man be found indolent enough to decline a little more trouble for placing them beyond the reach of question... …

In enumerating the defects of the constitution, it would be wrong to count among them what is only the error of particular persons. In December, 1776, our circumstances being much distressed, it was proposed in the House of Delegates to create a dictator, invested with every power legislative, executive, and judiciary, civil and military, of life and of death, over our persons and over our properties; and in June, 1781, again under calamity, the same proposition was repeated, and wanted a few votes only of being passed. One who entered into this contest, from a pure love of liberty, and a sense of injured rights, who determined to make every sacrifice, and to meet every danger, for! the re-establishment of those rights on a firm basis, who did not mean to expend his blood and substance for the wretched purpose of changing this master for that, but to place the powers of governing him in a plurality of hands of his own choice, so that the corrupt will of one man might in future oppress him, must stand confounded and dismayed when he is told that a considerable portion of that plurality had meditated the surrender of them into a single hand, and, in lieu of a limited monarch, to deliver him over to a despotic one! …

Our situation is, indeed, perilous, and I hope my countrymen will be sensible of it, and will apply at a proper season the proper remedy; which is a convention to fix the constitution, to amend its defects, to bind up the several branches of government by certain laws, which, when they transgress, their acts shall become nullities; to render unnecessary an appeal to the people, or, in other words, a rebellion, on every infraction of their rights, on the peril that their acquiescence shall be construed into an intention to surrender those rights.