Historic Document

The Constitution’s Bicentennial: Commemorating the Wrong Document? (1987)

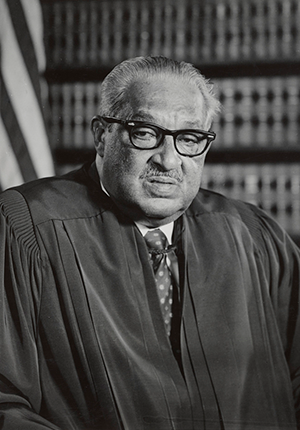

Thurgood Marshall | 1987

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993) was the NAACP’s chief lawyer in many of its landmark cases challenging segregation and the denial of basic rights to Black Americans, including Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall later served as Solicitor General of the United States, and, in 1967, he became the first African American Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Twenty years later, he delivered the following address as Americans prepared to commemorate the bicentennial of the framing of the United States Constitution. In this famous speech, Marshall argued that the Constitution was a “living document.” In turn, he strongly criticized its original flaws and celebrated the efforts of successive generations of Americans to push towards greater freedom and equality over time, from the Civil War and the ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments to the achievements of the civil rights movement and beyond.

.

Selected by

Christopher Brooks

Professor of History, East Stroudsburg University

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Document Excerpt

. . . I do not believe that the meaning of the Constitution was forever ‘fixed’ at the Philadelphia Convention. Nor do I find the wisdom, foresight, and sense of justice exhibited by the Framers particularly profound. To the contrary, the government they devised was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a civil war, and momentous social transformation to attain the system of constitutional government, and its respect for the individual freedoms and human rights, we hold as fundamental today. When contemporary Americans cite ‘The Constitution,’ they invoke a concept that is vastly different from what the Framers barely began to construct two centuries ago.

. . . ‘We the People.’ When the Founding Fathers used this phrase in 1787, they did not have in mind the majority of America’s citizens. . . . On a matter so basic as the right to vote, for example, Negro slaves were excluded, although they were counted for representational purposes – at three-fifths each. Women did not gain the right to vote for over a hundred and thirty years.

These omissions were intentional. The record of the Framers’ debates on the slave question is especially clear: The Southern States acceded to the demands of the New England States for giving Congress broad power to regulate commerce, in exchange for the right to continue the slave trade. . . .

Despite this clear understanding of the role slavery would play in the new republic, use of the words “slaves” and “slavery” was carefully avoided in the original document. Political representation in the lower House of Congress was to be based on the population of “free Persons” in each State, plus three-fifths of all “other Persons.” Moral principles against slavery, for those who had them, were compromised, with no explanation of the conflicting principles for which the American Revolutionary War had ostensibly been fought: the self-evident truths ‘that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ . . .

It took a bloody civil war before the thirteenth amendment could be adopted to abolish slavery, though not the consequences slavery would have for future Americans.

While the Union survived the Civil War, the Constitution did not. In its place arose a new, more promising basis for justice and equality, the fourteenth amendment, ensuring protection of the life, liberty, and property of all persons against deprivations without due process, and guaranteeing equal protection of the laws. And yet almost another century would pass before any significant recognition was obtained of the rights of black Americans to share equally even in such basic opportunities as education, housing, and employment, and to have their votes counted, and counted equally. . . .

What is striking is the role legal principles have played throughout America’s history in determining the condition of Negroes. They were enslaved by law, emancipated by law, disenfranchised and segregated by law; and, finally, they have begun to win equality by law. Along the way, new constitutional principles have emerged to meet the challenges of a changing society. The progress has been dramatic, and it will continue.

The men who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 could not have envisioned these changes. They could not have imagined, nor would they have accepted, that the document they were drafting would one day be construed by a Supreme Court to which had been appointed a woman and the descendent of an African slave. ‘We the People’ no longer enslave, but the credit does not belong to the Framers. It belongs to those who refused to acquiesce in outdated notions of ‘liberty,’ ‘justice,’ and ‘equality,’ and who strived to better them. . . .

Some may more quietly commemorate the suffering, struggle, and sacrifice that has triumphed over much of what was wrong with the original document, and observe the anniversary with hopes not realized and promises not fulfilled. I plan to celebrate the Bicentennial of the Constitution as a living document, including the Bill of Rights and the other amendments protecting individual freedoms and human rights.