Historic Document

The Laws (ca. 367-366 BC) and The Republic (ca. 380 BC)

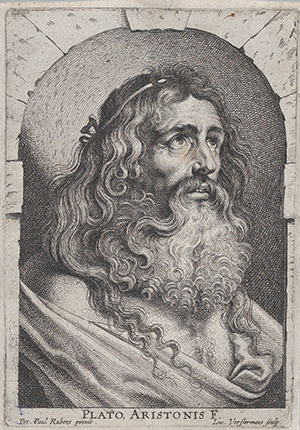

Plato | 367-366 BC and 380 BC

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Grace M. Pugh, 1985

Summary

Plato son of Ariston (ca. 428/7-ca. 348/47) was the author of The Apology of Socrates, The Republic, The Statesman, and The Laws, as well as a host of other dialogues with political themes. In the American colonies, Plato was best known for his Apology of Socrates. On the Founders, however, Plato’s greatest impact derived from (1) his contention that a republic must be small in size and population; and (2) Socrates’s discussion in The Republic of political psychology in relation to the fragility of the ancient Greek oligarchies and democracies.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

The Laws V

How then can we rightly order the distribution of the land? In the first place, the number of the citizens has to be determined, and also the number and size of the divisions into which they will have to be formed; and the land and the houses will then have to be apportioned by us as fairly as we can. The number of citizens can only be estimated satisfactorily in relation to the territory and the neighbouring states. The territory must be sufficient to maintain a certain number of inhabitants in a moderate way of life - more than this is not required; and the number of citizens should be sufficient to defend themselves against the injustice of their neighbours, and also to give them the power of rendering efficient aid to their neighbours when they are wronged. After having taken a survey of theirs and their neighbours’ territory, we will determine the limits of them in fact as well as in theory. And now, let us proceed to legislate with a view to perfecting the form and outline of our state. The number of our citizens shall be 5040 - this will be a convenient number; and these shall be owners of the land and protectors of the allotment.

The Republic 8.555b-566e

Well, I said, and how does the change from oligarchy into democracy arise? . . .

There can be no doubt that the love of wealth and the spirit of moderation cannot exist together in citizens of the same State to any considerable extent; one or the other will be disregarded. . . .

At present the governors, . . . treat their subjects badly; while they and their adherents, especially the young men of the governing class, are habituated to lead a life of luxury and idleness both of body and mind; they do nothing, and are incapable of resisting either pleasure or pain. . . .

They themselves care only for making money, and are as indifferent as the pauper to the cultivation of virtue. . . .

And, as in a body which is diseased the addition of a touch from without may bring on illness, and sometimes even when there is no external provocation a commotion may arise within - in the same way wherever there is weakness in the State there is also likely to be illness, of which the occasions may be very slight, the one party introducing from without their oligarchical, the other their democratical allies, and then the State falls sick, and is at war with herself; and may be at times distracted, even when there is no external cause. . . .

And then democracy comes into being after the poor have conquered their opponents, slaughtering some and banishing some, while to the remainder they give an equal share of freedom and power; and this is the form of government in which the magistrates are commonly elected by lot.

Yes, he said, that is the nature of democracy, whether the revolution has been effected by arms, or whether fear has caused the opposite party to withdraw.

And now what is their manner of life, and what sort of a government have they? for as the government is, such will be the man.

Clearly, he said. In the first place, are they not free; and is not the city full of freedom and frankness – a man may say and do what he likes? ‘Tis said so, he replied. And where freedom is, the individual is clearly able to order for himself his own life as he pleases?

Clearly. Then in this kind of State there will be the greatest variety of human natures?

There will. This, then, seems likely to be the fairest of States, being an embroidered robe which is spangled with every sort of flower. And just as women and children think a variety of colours to be of all things most charming, so there are many men to whom this State, which is spangled with the manners and characters of mankind, will appear to be the fairest of States. . . .

Say then, my friend, in what manner does tyranny arise? – that it has a democratic origin is evident.

Clearly. And does not tyranny spring from democracy in the same manner as democracy from oligarchy – I mean, after a sort?

How? The good which oligarchy proposed to itself and the means by which it was maintained was excess of wealth – am I not right?

Yes. And the insatiable desire of wealth and the neglect of all other things for the sake of money-getting was also the ruin of oligarchy?

True. And democracy has her own good, of which the insatiable desire brings her to dissolution?

What good? Freedom, I replied; which, as they tell you in a democracy, is the glory of the State – and that therefore in a democracy alone will the freeman of nature deign to dwell.

Yes; the saying is in everybody’s mouth. I was going to observe, that the insatiable desire of this and the neglect of other things introduces the change in democracy, which occasions a demand for tyranny.

How so? When a democracy which is thirsting for freedom has evil cupbearers presiding over the feast, and has drunk too deeply of the strong wine of freedom, then, unless her rulers are very amenable and give a plentiful draught, she calls them to account and punishes them, and says that they are cursed oligarchs. . . .

By degrees the anarchy finds a way into private houses . . . .

[T]he father grows accustomed to descend to the level of his sons and to fear them, and the son is on a level with his father, he having no respect or reverence for either of his parents; . . . the stranger is quite as good as either. . . .

And these are not the only evils, I said – there are several lesser ones: In such a state of society the master fears and flatters his scholars, and the scholars despise their masters and tutors; young and old are all alike; and the young man is on a level with the old, and is ready to compete with him in word or deed; and old men condescend to the young and are full of pleasantry and gaiety; they are loth to be thought morose and authoritative, and therefore they adopt the manners of the young. . . .

And above all, I said, and as the result of all, see how sensitive the citizens become; they chafe impatiently at the least touch of authority and at length, as you know, they cease to care even for the laws, written or unwritten; they will have no one over them.

Yes, he said, I know it too well. Such, my friend, I said, is the fair and glorious beginning out of which springs tyranny. . . .

But what is the next step? The ruin of oligarchy is the ruin of democracy; the same disease magnified and intensified by liberty overmasters democracy – the truth being that the excessive increase of anything often causes a reaction in the opposite direction; and this is the case not only in the seasons and in vegetable and animal life, but above all in forms of government.

True. The excess of liberty, whether in States or individuals, seems only to pass into excess of slavery.

Yes, the natural order. And so tyranny naturally arises out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme form of liberty? . . .

The people have always some champion whom they set over them and nurse into greatness. . . .

This and no other is the root from which a tyrant springs; when he first appears above ground he is a protector.

Yes, that is quite clear. How then does a protector begin to change into a tyrant? . . .

[T]he protector of the people is like him; having a mob entirely at his disposal, he is not restrained from shedding the blood of kinsmen; by the favourite method of false accusation he brings them into court and murders them . . . ; some he kills and others he banishes, at the same time hinting at the abolition of debts and partition of lands: and after this, what will be his destiny? Must he not either perish at the hands of his enemies, or from being a man become a wolf – that is, a tyrant? . . .

After a while he is driven out, but comes back, in spite of his enemies, a tyrant full grown.

That is clear. And if they are unable to expel him, or to get him condemned to death by a public accusation, they conspire to assassinate him.

Yes, he said, that is their usual way. Then comes the famous request for a bodyguard, which is the device of all those who have got thus far in their tyrannical career – ‘Let not the people’s friend,’ as they say, ‘be lost to them.’