Historic Document

One Country, One Constitution, One People (1866)

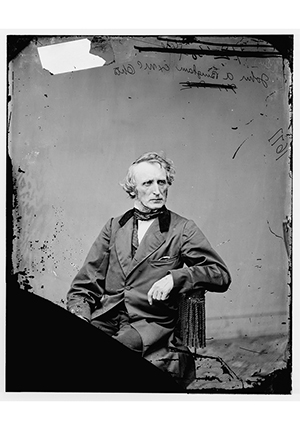

John Bingham | 1866

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy photograph collection

Summary

John Bingham of Ohio was a leading Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives during Reconstruction and the primary author of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because of Bingham’s crucial role in framing this constitutional text, Justice Hugo Black would later describe him as the Fourteenth Amendment’s James Madison. Bingham delivered this speech in defense of an early draft of the Fourteenth Amendment, advancing a bold vision of nationally protected rights. Today, the Bill of Rights represents a charter of national freedom applying to all levels of government: national, state, and local. However, when it was added to the U.S. Constitution in 1791, the Bill of Rights applied only to the national government—not to the states. Eventually, the Supreme Court embraced Bingham’s vision of nationally protected rights through a process known as “incorporation”—applying many core Bill of Rights protections like free speech and religious liberty to abuses against state governments.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

Document Excerpt

I think, sir, that the honorable gentleman from Vermont [Mr. Woodbridge] has uttered words that ought to be considered and accepted by gentlemen of the House, when he says that the action of this Congress in its effect upon the future prosperity of the country will be felt by generations of men after we shall all have paid the debt of nature. I believe, Mr. Speaker, as I have had occasion to say more than once, that the people of the United States have intrusted to the present Congress in some sense the care of the Republic, not only for the present, but for all the hereafter. Your committee, sir, would not have sent to this House for its consideration this proposition but for the conviction that its adoption by Congress and its ratification by the people of the United States is essential to the safety of all the people of every State. I repel the suggestion made here in the heat of debate, that the [Joint Committee on Reconstruction] or any of its members who favor this proposition seek in any form to mar the Constitution of the country, or take away from any State any right that belongs to it, or from any citizen of any State any right that belongs to him under that Constitution. The proposition pending before the House is simply a proposition to arm the Congress of the United States, by the consent of the people of the United States, with the power to enforce the bill of rights as it stands in the Constitution today. It “hath that extent—no more.”

Gentlemen who seem to be very desirous (although it has very recently come to them) to stand well with the President of the United States [Andrew Johnson], if they will look narrowly into the message which he addressed to this Congress at the opening of the session will find that the proposition pending is approved in that message. The president in the message tells this House and the country that “the American system rests on the assertion of the equal right of every man to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

But, sir, that statement rests upon higher authority than that of the President of the United States. It rests upon the authority of the whole people of the United States, speaking through their Constitution as it has come to us from the hands of the men who framed it. The words of that great instrument are:

“The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States.” (Article VI, Sect. II)

“No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” (Amendment V) . . .

Gentlemen admit the force of the provisions in the bill of rights, that the citizens of the United States shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States in the several states, and that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; but they say, “We are opposed to its enforcement by act of Congress under an amended Constitution, as proposed.” That is the sum and substance of all the argument we have heard on this subject. Why are gentlemen opposed to the enforcement of the bill of rights, as proposed? Because they aver it would interfere with the reserved rights of the States! Who ever before heard that any State had reserved to itself the right, under the Constitution of the United States, to withhold from any citizen of the United States within its limits, under any pretext whatever, any of the privileges of a citizen of the United States, or to impose upon him, no matter from what State he may have come, any burden contrary to that provision of the Constitution which declares that the citizen shall be entitled in the several States to all the immunities of a citizen of the United States?

What does the word immunity in your Constitution mean? Exemption from unequal burdens. Ah! Say gentlemen who oppose this amendment, we are not opposed to equal rights; we are not opposed to the bill of rights that all shall be protected alike in life, liberty, and property we are only opposed to enforcing it by national authority, even by consent of the loyal people of all the States. . . .

The question is, simply, whether you will give by this amendment to the people of the United States, the power, by legislative enactment, to punish officials of States for violation of the oaths enjoined upon them by their Constitution? That is the question, and the whole question. The adoption of the proposed amendment will take from the States no rights that belong to the States. They elect their Legislatures; they enact their laws for the punishment of crimes against life, liberty, or property but in the event of the adoption of this amendment, if they conspire together to enact laws refusing equal protection to life, liberty, or property, the Congress is thereby vested with the power to hold them to answer before the bar of the national courts for the violation of their oaths and of the rights of their fellow men. Why should it not be so? Is the bill of rights to stand in our Constitution hereafter, as in the past five years within eleven states, a mere dead letter?

Mr. Speaker, it appears to me that this very provision of the bill of rights brought in question this day, upon this trial before the House, more than any other provision of the Constitution, makes that unity of government which constitutes us one people, by which and through which American nationality came to be, and only by the enforcement of which can American nationality continue to be. . . .

Why, sir, what an anomaly is presented today to the world! We have the power to vindicate the personal liberty and all the personal rights of the citizen on the remotest sea, under the frowning batteries of the remotest tyranny on this earth, while we have not the power in time of peace to enforce the citizens’ rights to life, liberty, and property within the limits of South Carolina after her State government shall be recognized and her constitutional relations restored. . . .

As a further security for the enforcement of the Constitution, and especially this sacred bill of rights, to all the citizens and all the people of the United States, it is further provided that members of the several State Legislatures and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by oath or affirmation to support this Constitution. The oath, the most solemn compact which man can make with his Maker, was to bind the State legislatures, executive officers, and judges to sacredly respect the Constitution and all the rights secured by it. . . . [I]t is surprising that the framers of the Constitution omitted to insert an express grant of power in Congress to enforce by penal enactment these great canons of the supreme law, securing to all the citizens in every State all the privileges and immunities. . .

What more could have been added to that instrument to secure the enforcement of these provisions of the bill of rights in every State. . . . Nothing at all. And I am perfectly confident that that grant of power would have been there but for the fact that its insertion in the Constitution would have been utterly incompatible with the existence of slavery in any State; for although slaves might have not have been admitted to be citizens they must have been admitted to be persons. That is the only reason why it was not there. There was a fetter upon the conscience of the nation. Thank God, that fetter has been broken; it has turned to dust before the breath of the people, speaking as the voice of God and solemnly ordaining that slavery is forever prohibited everywhere within the Republic except as punishment for crime on due conviction. . . .

It seems to me equally clear if you intend to have these thirty-six States one under our Constitution, if you intend that every citizen of every State shall in the hereafter have the immunities and privileges of citizens in the several States, you must amend the Constitution. It cannot be otherwise. Restore those states with a majority of rebels to political power and they will cast their ballots to exclude from the protection of the laws every man who bore arms in the defense of the Government. The loyal minority of white citizens and the disfranchised colored citizens will be utterly powerless. There is no efficient remedy for it without an amendment to your Constitution.