Historic Document

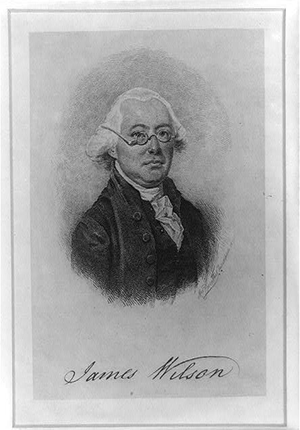

Madison and Wilson, Constitutional Convention Speeches (1787)

James Madison and James Wilson | 1787

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

On June 18, 1787, Alexander Hamilton held the floor for the entire day’s debate, delivering a general description of republican government that related it closely to the model that had evolved in the United Kingdom. The speech occurred at a pitched moment in the debate over the “Connecticut Compromise” and the struggle over “proportional representation” of the population or “equal representation” of the states. The following day, June 19, James Madison and James Wilson spoke at length on the question of representation. This period of debate reflects in many respects the climax of the Convention: the decision on the “Connecticut Compromise.” Here, Madison and Wilson justify their strong convictions in opposition to the compromise, and, in particular, what they regarded as the fig-leaf of a reservation of the power to originate money bills in the House of Representatives. The Connecticut Compromise was only consummated when they relented in their opposition (following George Washington’s guidance).

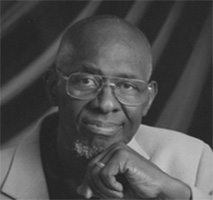

Selected by

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

Mr. M(adison). Much stress had been laid by some gentlemen on the want of power in the Convention to propose any other than a federal plan. To what had been answered by others, he would only add, that neither of the characteristics attached to a federal plan would support this objection: One __characteristic, was that in a federal Government, the power was exercised not on the people individually; but on the people collectively, on the States. Yet in some instances as in piracies, captures &c. the existing Confederacy, and in many instances, the amendments to it (proposed by Mr. Patterson) must operate immediately on individuals. The other characteristic was, that a federal Govt. derived its appointments not immediately from the people, but from the States which they respectively composed. Here too were facts on the other side. In two of the States, Connect. and Rh. Island, the delegates to Congs. were chosen, not by the Legislatures, but by the people at large; and the plan of Mr. P. intended no change in this particular.

It had been alledged (by Mr. Patterson) that the Confederation having been formed by unanimous consent, could be dissolved by unanimous Consent only. Does this doctrine result from the nature of compacts? does it arise from any particular stipulation in the articles of Confederation? If we consider the federal union as analogous to the fundamental compact by which individuals compose one Society, and which must in its theoretic origin at least, have been the unanimous act of the component members, it cannot be said that no dissolution of the compact can be effected without unanimous consent. a breach of the fundamental principles of the compact by a part of the Society would certainly absolve the other part from their obligations to it. If the breach of any article by any of the parties, does not set the others at liberty, it is because, the contrary is implied in the compact itself, and particularly by that law of it, which gives an indefinite authority to the majority to bind the whole in all cases. This latter circumstance shews that we are not to consider the federal Union as analogous to the social compact of individuals: for if it were so, a Majority would have a right to bind the rest, and even to form a new Constitution for the whole, which the Gentn: from N. Jersey would be among the last to admit. If we consider the federal union as analogous not to the (social} compacts among individual men: but to the conventions among individual States. What is the doctrine resulting from these conventions? Clearly, according to the Expositors of the law of Nations, that a breach of any one article, by any one party, leaves all the other parties at liberty, to consider the whole convention as dissolved, unless they choose rather to compel the delinquent party to repair the breach. In some treaties indeed it is expressly stipulated that a violation of particular articles shall not have this consequence, and even that particular articles shall remain in force during war, which in general is understood to dissolve all subsisting Treaties. …

The great difficulty lies in the affair of Representation; and if this could be adjusted, all others would be surmountable. It was admitted by both the gentlemen from N. Jersey, (Mr. Brearly and Mr. Patterson) that it would not be just to allow Virga. which was 16 times as large as Delaware an equal vote only. Their language was that it would not be safe for Delaware to allow Virga. 16 times as many votes. The expedient proposed by them was that all the States should be thrown into one mass and a new partition be made into 13 equal parts. Would such a scheme be practicable? The dissimilarities existing in the rules of property, as well as in the manners, habits and prejudices of the different States, amounted to a prohibition of the attempt. It had been found impossible for the power of one of the most absolute princes in Europe (K. of France) directed by the wisdom of one of the most enlightened and patriotic Ministers (Mr. Neckar) that any age has produced, to equalize in some points only the different usages & regulations of the different provinces. But admitting a general amalgamation and repartition of the States, to be practicable, and the danger apprehended by the smaller States from a proportional representation to be real; would not a particular and voluntary coalition of these with their neighbours, be less inconvenient to the whole community, and equally effectual for their own safety. If N. Jersey or Delaware conceive that an advantage would accrue to them from an equalization of the States, in which case they would necessarily form a junction with their neighbors, why might not this end be attained by leaving them at liberty by the Constitution to form such a junction whenever they pleased? and why should they wish to obtrude a like arrangement in all the States, when it was, to say the least, extremely difficult, would be obnoxious to many of the States, and when neither the inconveniency, nor the benefit of the expedient to themselves, would be lessened, by confining it to themselves.

Mr. Wilson could not admit the doctrine that when the Colonies became independent of G. Britain, they became independent also of each other. He read the Declaration of Independence, observing thereon that the United Colonies were declared to be free & independent States; and inferring that they were independent, not Individually but Unitedly and that they were confederated as they were independent, States. Col. Hamilton assented to the doctrine of Mr. Wilson. He denied the doctrine that the States were thrown into a State of nature. He was not yet prepared to admit the doctrine that the Confederacy could be dissolved by partial infractions of it. He admitted that the States met now on an equal footing but could see no inference from that against concerting a change of the system in this particular. He took this occasion of observing for the (purpose of) appeasing the fears of the (small) States, that two circumstances would render them secure under a national Govt. in which they might lose the equality of rank they now hold: one was the local situation of the 3 largest States Virga. Masts. & Pa. They were separated from each other by distance of place, and equally so by all the peculiarities which distinguish the interests of State from those of another. No combination therefore could be dreaded. In the second place, as there was a gradation in the States from Va. the largest down to Delaware the smallest, it would always happen that ambitious combinations among a few States might & wd. be counteracted by defensive combinations of greater extent among the rest. No combination has been seen among large Counties merely as such, agst. lesser Counties. The more close the Union of the States, and the more compleat the authority of the whole; the less opportunity will be allowed the stronger States to injure the weaker.