Historic Document

To the Public (1786)

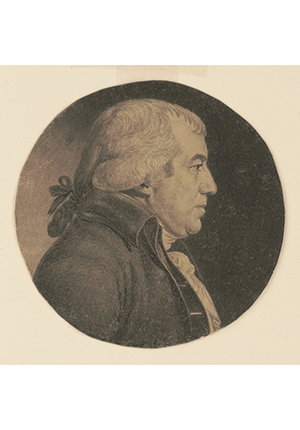

James Iredell | 1786

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Few issues have proved quite as challenging or divisive as charting the origins of judicial review in the early United States. For generations, John Marshall’s famous defense of the practice in the 1803 Supreme Court case, Marbury v. Madison, has served as the dominant touchstone. Many also emphasize Alexander Hamilton’s earlier arguments issued in defense of judicial power in Federalist 78. While these sources are more famous, each drew on arguments James Iredell made in North Carolina prior to the Constitutional Convention, in particular in his essay, “To the Public,” published in a New Bern newspaper in 1786. In it, Iredell, who would later serve as a Justice on the United States Supreme Court, defended the controversial view that judges ought to enforce constitutional limits on state legislative power. Many, if not most, at the time assumed that legislatures most closely represented the people at-large, so the thought that unelected judges might overturn the laws that these bodies made was highly controversial and seemingly antithetical to republican government. To counter this pervasive assumption, Iredell argued that the essence of judicial power was to decide cases according to law. If judges, therefore, in their ordinary judicial business, found themselves presented with a conflict of laws—an act of the assembly that violated the constitution—it was their duty to enforce the constitution, as all agreed it alone was supreme fundamental law.

Selected by

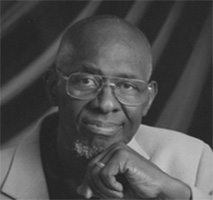

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Document Excerpt

As the Question concerning the Power of the Assembly deeply concerns every Man in the State, I shall make no apology for delivering my Sentiments upon it. They are indeed only the sentiments of an obscure Elector, but one who he trust has rights that he as much values, though with less ability to defend them, as the proudest Member of Assembly whatever.

I have not lived so short a time in the State, nor with so little interest in its concerns, as to forget the extreme anxiety with which all of us were agitated in forming the Constitution, a Constitution which we considered as the fundamental basis of our Government, unalterable but by the same high power which established it, and therefore to be deliberated on with the greatest caution because if it contained any evil principle the Government formed under it must be annihilated before the evil could be corrected. It was of course to be considered, how to impose restrictions on the Legislature that might still leave it free to all useful purposes, but at the same time guard against the abuses of unlimited power, which was not to be trusted without the most imminent danger to any Man or Body of Men on Earth. We had not only been sickened and disgusted for years with the high and almost impious language from Great Britain, of the omnipotent power of the British Parliament, but had severely smarted under its Effects….We were not ignorant of the theory, of the necessity of the Legislature being absolute in all cases, because it was the great ground of the British Pretensions. But this was a mere speculative principle, which Men at ease and leisure thought proper to assume. When we were at liberty to form a Government as we thought best, without regard to that or any theoretical principle we did not approve of, we decisively gave our sentiments against it, being willing to run all the risques of a Government to be conducted on the principles then laid as the basis of it. The instance was new in the Annals of Mankind. …

I have therefore no doubt, but that the power of the Assembly is limited and defined by the Constitution. It is a Creature of the Constitution…. The People have chosen to be governed under such and such principles. They have not chosen to be governed, or promised to submit upon any other. …

These are Consequences that seem so natural, and indeed so irresistible, that I do not observe they have been much contested. The great argument is, that though the Assembly have not a right to violate the Constitution, yet if they in fact do so the only remedy is, either by an humble Petition that the Law may be repealed, or an universal resistance of the People. But that in the meantime, their Act, whatever it is, is to be obeyed as a Law, for the judicial power is not to presume to question the power of an Act of Assembly. …

These two Remedies then being rejected, it remains to be enquired whether the Judicial Power hath any Authority to interfere in such a case. The duty of that Power, I conceive, in all cases, is to decide according to the Laws of the State. It will not be denied, I suppose, that the Constitution is a Law of the State, as well as an Act of Assembly, with this difference only, that it is the fundamental Law, and unalterable by the Legislature which derives all its power from it. One Act of Assembly may repeal another Act of Assembly. For that reason the latter Act is to be obeyed, and not the former. An Act of Assembly cannot repeal the Constitution or any part of it. For that reason an Act of Assembly inconsistent with the Constitution is void, and cannot be obeyed without disobeying the Superior Law to which we were previously and irrevocably bound. The Judges therefore must take care at their peril that every Act of Assembly they presume to enforce is warranted by the Constitution, if it is not they act without lawful authority. This is not an usurped or a discretionary Power, but one inevitably resulting from the constitution of their Office, they being judges for the benefit of the whole People, not mere Servants of the Assembly.