Historic Document

De Jure Belli ac Pacis “On the Law of War and Peace” (1625)

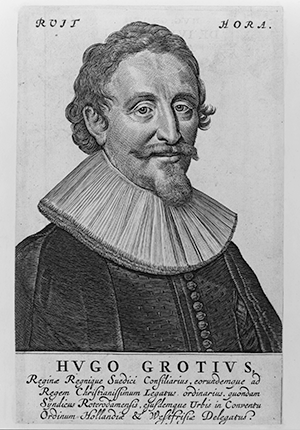

Hugo Grotius | 1625

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) was a Dutch scholar whose influential legal work, De Jure Belli ac Pacis "On the Law of War and Peace", published in 1625, was a path-breaking work in the theory of international law. In the introduction or “Prolegomena,” Grotius sets forth the philosophic arguments he will develop in the ensuing text, treating the issues of national sovereignty and distinguishing between unjust and just wars between nations. Whether Grotius agreed with or departed from the Hobbesian conception of divine authority, the law of nature, and the grounds of obligation was a topic of interest and controversy among scholars of his time and ours. Indeed, his influence on myriad European and American authors and statesmen extended beyond law of nations theory to natural rights and social contract theory as well.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

“Prolegmena”

I. The Civil Law, whether that of the Romans, or of any other People, many have undertaken, either to explain by Commentaries, or to draw up into short Abridgments: But that Law, which is common to many Nations or Rulers of Nations, whether derived from Nature, or instituted by Divine Commands, or introduced by Custom and tacit Consent, few have touched upon, and none hitherto treated of universally and methodically; tho’ it is the Interest of Mankind that it should be done.

III. . . . And indeed this Work is the more necessary, since we find some, both in this and in former Ages, so far despising this Sort of Right, as if it were nothing but an empty Name. The Saying of Euphemus in Thucydides is almost in every ones Mouth, To a King or Sovereign City, nothing is unjust that is profitable. Not unlike to which is this, That amongst the Great the stronger is the juster Side; and, That no State can be governed without Injustice. Besides, the Disputes that happen between Nations or Princes, are commonly decided at the Point of the Sword. Now, it is not only the Opinion of the Vulgar, that War is a Stranger to all Justice, but many Sayings uttered by Men of Wisdom and Learning, give Strength to such an Opinion. And indeed, nothing is more frequent than the mentioning of Right and Arms, as opposite to one another.

VI. . . . Now amongst the Things peculiar to Man, is his Desire of Society, that is, a certain Inclination to live with those of his own Kind, not in any Manner whatever, but peaceably, and in a Community regulated according to the best of his Understanding; which Disposition the Stoicks termed Ὀικείωσιν. Therefore the Saying, that every Creature is led by Nature to seek its own private Advantage, expressed thus universally, must not be granted. . . .

VIII. This Sociability, which we have now described in general, or this Care of maintaining Society in a Manner conformable to the Light of human Understanding, is the Fountain of Right, properly so called; to which belongs the Abstaining from that which is another’s, and the Restitution of what we have of another’s, or of the Profit we have made by it, the Obligation of fulfilling Promises, the Reparation of a Damage done through our own Default, and the Merit of Punishment among Men.

XII. And this now is another Original of Right, besides that of Nature, being that which proceeds from the free Will of God, to which our Understanding infallibly assures us, we ought to be subject: And even the Law of Nature itself, whether it be that which consists in the Maintenance of Society, or that which in a looser Sense is so called, though it flows from the internal Principles of Man, may notwithstanding be justly ascribed to God, because it was his Pleasure that these Principles should be in us. And in this Sense Chrysippus and the Stoicks said, that the Original of Right is to be derived from no other than Jupiter himself; from which Word Jupiter it is probable the Latins gave it the Name Jus.

XIII. There is yet this farther Reason for ascribing it to God, that God by the Laws which he has given, has made these very Principles more clear and evident, even to those who are less capable of strict Reasoning, and has forbid us to give way to those impetuous Passions, which, contrary to our own Interest, and that of others, divert us from following the Rules of Reason and Nature; for as they are exceeding unruly, it was necessary to keep a strict Hand over them, and to confine them within certain narrow Bounds.

XXIV. If there is no Community which can be preserved without some Sort of Right, as Aristotle proved by that remarkable Instance of Robbers, certainly the Society of Mankind, or of several Nations, cannot be without it; which was observed by him who said, That a base Thing ought not to be done, even for the Sake of ones Country. Aristotle inveighs severely against those, who, though they would not have any to govern amongst themselves, but he that has a Right to it, yet in regard to Foreigners are not concerned whether their Actions be just or unjust.

LXII. And now, whatever Liberty I have taken in judging of the Opinions and Writings of others, I desire and beseech all those, into whose Hands this Treatise shall come, to take the same with me. They shall no sooner admonish me of my Mistakes, than I shall follow their Admonitions. And moreover, if I have said any thing contrary either to Piety, or to good Manners, or to Holy Scripture, or to the Consent of the Christian Church, or to any Kind of Truth, let it be unsaid again.