Historic Document

The Constitution: Is it Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery? (1860)

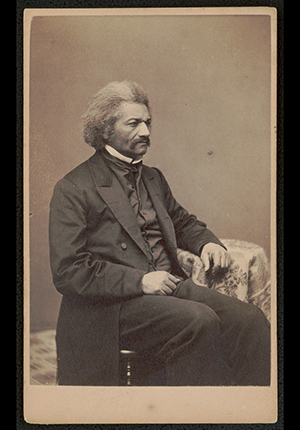

Frederick Douglass | 1860

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Summary

Frederick Douglass was one of the most important and influential statesmen of the nineteenth century. After escaping from slavery in 1838, Douglass originally joined the radical abolitionist effects of William Lloyd Garrison. By the 1850s, however, Douglass had developed his own understanding of the American Constitution. In this speech, delivered before the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, Scotland, Douglass rejects the pro-slavery interpretations of both his former mentor Garrison and Chief Justice Taney in the Dred Scott case. Douglass points out that the words “slave” and “slavery” appear nowhere in the document and he insists that the text is best understood as tilted towards freedom. The Fifth Amendment, for example, declares that no person could be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Black Americans, even if not yet considered citizens, were certainly persons who deserved the protection of the national Bill of Rights. Douglass’s theories not only influenced abolitionist members of Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, his efforts on behalf of black suffrage helped fuel the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

Kurt Lash

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

Document Excerpt

1st, Does the United States Constitution guarantee to any class or description of people in that country the right to enslave, or hold as property, any other class or description of people in that country? 2nd, Is the dissolution of the union between the slave and free States required by fidelity to the slaves, or by the just demands of conscience? Or, in other words, is the refusal to exercise the elective franchise, and to hold office in America, the surest, wisest, and best way to abolish slavery in America?

To these questions the Garrisonians say Yes. They hold the Constitution to be a slaveholding instrument, and will not cast a vote or hold office, and denounce all who vote or hold office, no matter how faithfully such persons labour to promote the abolition of slavery. I, on the other hand, deny that the Constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man, and believe that the way to abolish slavery in America is to vote such men into power as will use their powers for the abolition of slavery. . . .

It so happens that no such words as “African slave trade,” no such words as “slave insurrections,” are anywhere used in that instrument. These are the words of that orator, and not the words of the Constitution of the United States. . . .

In all matters where laws are taught to be made the means of oppression, cruelty, and wickedness, I am for strict construction. I will concede nothing. It must be shown that it is so nominated in the bond. The pound of flesh, but not one drop of blood. . . . The Supreme Court of the United States lays down this rule, and it meets the case exactly—“Where rights are infringed—where the fundamental principles of the law are overthrown— where the general system of the law is departed from, the legislative intention must be expressed with irresistible clearness.” The same court says that the language of the law must be construed strictly in favour of justice and liberty. . ..

[T]he Constitution declares that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; it secures to every man the right of trial by jury, the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus—the great writ that put an end to slavery and slave-hunting in England—and it secures to every State a republican form of government. Anyone of these provisions in the hands of abolition statesmen, and backed up by a right moral sentiment, would put an end to slavery in America.