Historic Document

One Man Power vs. Congress (1866)

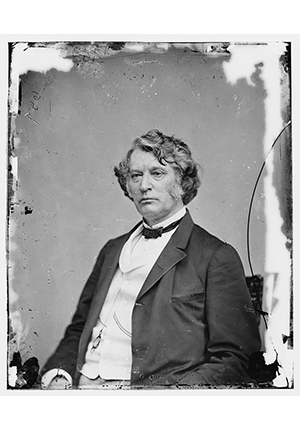

Charles Sumner | 1866

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy photograph collection

Summary

Charles Sumner was a leading radical voice in the U.S. Senate during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Massachusetts Senator often stood alone politically, representing the most ambitious stands on issues of racial equality and Southern reconstruction. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the Republican Congress divided over how best to conceive of the political status of the ex-Confederate States. Offering a bold theory, Sumner argued that when the ex-Confederate States seceded from the Union, they had committed state “suicide” and reverted to the status of mere territories of the United States. As a result, Congress had broad authority to govern the ex-Confederate States and impose various conditions on them before they could be readmitted to the Union. On the opening day of its new session in December 1865, the Republican-controlled Congress excluded Southern representatives until the ex-Confederate states met certain requirements. In this powerful speech, Sumner defended Congress’s authority to exclude the Southern representatives and attacked President Andrew Johnson for undermining congressional efforts to reconstruct the ex-Confederate states, protect the rights of African Americans, and ensure a Second Founding for post-Civil War America.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

Document Excerpt

It is now more than a year since I last had the honor of addressing my fellow citizens of man. On that occasion I dwelt on what seemed to be the proper policy towards the states recently in rebellion—insisting that it was our duty, while renouncing indemnity for the past, to obtain at least security for the future; and this security I maintained could be found only in the exclusion of ex-rebels from political power . . .

The two parties to the controversy are the President on the one side and the people of the United States in Congress assembled on the other side; the first representing the Executive; the second representing the Legislative. It is the One Man Power vs. Congress. Of course each of these performs its part in the government; but until now it has always been supposed that the Legislative gave the laws to the Executive, not that the Executive gave the law to the Legislative. Perhaps this irrational assumption becomes more astonishing when it is considered, that the actual President, besides being the creature of an accident, is inferior in ability and character, while the House of Representatives is eminent in both respects. A President, who has already sunk below any other president, even Buchanan, madly undertakes to give the law to a House of Representatives, which there is reason to believe is the best that has sat since the formation of the Constitution. Thus, in looking at the parties, we are tempted to exclaim - such a President dictating to such a Congress! . . .

The question at this time is one of the vastest ever presented for practical decision, involving the name and weal of this Republic at home and abroad. It is not a military question; it is a question of statesmanship. We are to secure by counsel what was won by the war. Failure now will make the war itself a failure, surrender now will undo all our victories. Let the President prevail, and straightway the plighted faith of the Republic will be broken; the national creditor and the national freedman will be sacrificed; the Rebellion itself will flaunt its insulting power; the whole country in its length of wealth will be disturbed; and the rebel region will be handed over to misrule and anarchy. Let Congress prevail and all this will be reversed; the plighted faith of the Republic will be preserved; the national creditor and the national freedman will be protected; the Rebellion itself will be trampled out forever; the whole country in its length and breadth will be at peace; the rebel region, no longer harassed by controversy and injustice, will enjoy richest the fruits of security and reconciliation. To labor for this cause may well tempt the young and rejoice the old.

And, now to-day, I protest again against any admission of ex-rebels and the great partnership of this Republic, and I renew the claim of irreversible guarantees especially applicable to the national creditor and the national freedman; insisting now, as I did a year ago, that it is our duty, while renouncing indemnity for the past, to obtain at least security for the future. Here I stand. At the close of a terrible war—which has wasted our treasure—which has murdered our fellow citizens—which has filled the land with funerals—which has maimed and wounded many whom it has spared from death—and which has broken up the very foundations of peace—our first duty is to provide safeguards for the future. This can be only by provisions, sure, fundamental irrepealable, which shall fix forever the results of the war—the obligations of government—and the equal rights of all. Such is the suggestion of Common prudence and of self-defence, as well as of common honesty. To this end we must make haste slowly, states which precipitated themselves out of Congress must not be allowed to precipitate themselves back. They must not be allowed to enter those halls which they treasonably deserted, until we have every reasonable assurance of future good conduct. We must not admit them and then repent our folly. . . .

From all quarters we learn that after the surrendering of Lee, the rebels were ready for any terms, if they could escape with their lives. They were vanquished and they knew it. The rebellion was crushed and they knew it. They hardly expected to save a small fraction of their property. They did not expect to save their political power. They were too sensible not to see that participants in rebellion could not pass at once into the partnership of government. They made up their minds to exclusion. They were submissive. There was nothing they would not do, even to the extent of enfranchising their freedmen and providing for them homesteads. Had the national Government merely taken advantage of this plastic condition, it might have stamped Equal Rights upon the whole people, as upon molten wax, while it fixed the immutable conditions of permanent peace. The question of reconstruction would have been settled before it arose. It is sad to think that this was not done. Perhaps, in all history there is no instance of such an opportunity lost. . . .

Glance, if you please, at that Presidential Policy—so constantly called “my policy”— which is now so vehemently pressed upon the country and you will find that it pivots on at least two alarming blunders—as can be easily seen; first, in setting up the One Man Power, as the source of jurisdiction over this great question; and secondly, in using the One Man Power for the restoration of rebels to place and influence, so that good Unionists, whether white or black, are rejected, and the rebellion itself is revived in the new government. Each of these assumptions is an enormous blunder. . . .

Pray, Sir, where in the Constitution do you find any sanction of the One Man Power as the source of this extraordinary jurisdiction? I had always supposed that the President was the Executive bound to see the laws faithfully executed; but not powered to make Laws. . . . [Y]et the President has assumed legislative power, even to the extent of making laws and constitutions for States. You all know that at the close of the war, when the rebel states were without lawful governments, he assumed to supply them. In this business of reconstruction, he assumed to determine who should vote, and also to affix conditions for adoption by the Conventions. Look, if you please, at the character of this assumption. The President, from the Executive Mansion at Washington, reaches his long Executive arm into certain states and dictates their Contributions. Surely there is nothing executive in this assumption. It is not even military. It is legislative, pure and simple, and nothing else. It is an attempt by the One Man Power to do what can be done only by the legislative branch of the government. And yet so perverse is the President in absorbing to himself all power over the reconstruction of the rebel states, that he insists that Congress must accept his work without addition or subtraction. He can impose conditions; Congress cannot. He can determine who shall vote; Congress cannot. His jurisdiction is not only complete but exclusive. If all this be so, then has our President a most extraordinary power never before dreamed of. He may exclaim with Louis XIV: “The State, it is I,” while, like this magnificent king, he sacrifices the innocent . . . His whole “policy” is a “revocation” of all that has been promised and all that we have a right to expect. . . .

There is another provision of the Constitution, by which, according to a judgment of the Supreme Court of the United States, this question is referred to Congress and not to the President. I refer to the provision that “The United States shall guarantee to every state in this Union a Republican government.” On these words Chief Justice Taney, speaking for the Supreme Court, has adjudged, “that it rests with Congress to decide what government is the established one in a State; as the United States guarantee to each state a republican government, Congress must necessarily decide what government is established in a state before it can determine whether it is republican or not; and that undoubtedly a military government established as the permanent government of a state would not be a Republican government and it would be the duty of Congress to overthrow it.” . . .

And now the whole country is summoned by the President to recognize State governments created by Constitutions, thus illegitimate in origin and character. Without considering if they contain the proper elements of security for the future, or if they are republican in form and without any inquiry into the validity of their adoption; nay, in the very face of testimony, showing that they contain no elements of security for the future; that they are not republican in form; and that they have never been adopted by the loyal people, we are commanded to accept them; and when we hesitate, the President himself, leading the outcry, assails us with angry vituperation, flustered, it must be conferred, by a vulgarity without bounds. It is well that such a cause has such an advocate. . . .

The other blunder is of a different character. It is giving power to ex-rebels, at the expense of constant Unionists, white or black, and employing them in the work of reconstruction, so that the new governments continue to represent the rebellion. . . . The blunder is strange and unaccountable. ...

Partizans of the Presidential “policy” are in the habit of declaring that it is a continuation of the policy of the martyred Lincoln. This is a mistake. Would that he could rise from his bloody shroud to repell the calumny! . . .

I am not against pardon, clemency or magnanimity, except where they are at the expense of good men. I trust that they will always be practiced; but I insist that recent rebels shall not be admitted without proper precautions to the business of the firm. . . .

I was in Washington during the first month of the new Administration, destined to fill such an unhappy place in history. During this period I saw the President frequently, sometimes at the private house he then occupied and sometimes at his office in the Treasury. On these occasions the constant topic was “reconstruction,” which was considered in every variety and aspect. More than Once, I ventured to press upon him the duty and the renown of carrying out the principles of the Declaration of Independence and of founding the new governments in the rebel states on the consent of the governed, without any distinction of color. To this earnest appeal he replied on one occasion, as I sat with him alone in words which I can never forget; “On this question, Mr. Sumner, there is no difference between us. You and I are alike.” . . .

Only a short time afterwards there was a change which seemed like a summerset; and then ensued a strange sight. Instead of faithful Unionists recent rebels thronged the Presidential antichambers, rejoicing in a new-found favor. They made speeches at the President and he made speeches at them. A mutual sympathy was manifest. . . . Every where ex-rebels came out of their hiding-places. They walked the streets defiantly and asserted their old domination! Under the auspices of the President a new campaign was planned against the Republic, and they who failed in open war sought to enter the very citadel of political power. Victory, punctuated by so much loyal blood and treasure, was little better than a cypher. Slavery itself re-appeared in the spirit of Caste. Unionists, who had been trampled down by the Rebellion were trampled down still more by these Presidential governments. There was no liberty of the press or liberty of speech, and the lawlessness of Slavery began to rage anew.

Every day brought tidings that the rebellion was re-appearing in its essential essence. Amidst all professions of submission there was an immitigable hate to the national Government, and a prevailing injustice to the freedman. . . .

Meanwhile the Presidential madness has become more than ever manifest. It has shown itself in frantic efforts to defeat the Constitutional Amendment [the Fourteenth Amendment] proposed by Congress for adoption by the people. By this amendment certain safeguards are established. Citizenship is defined, and protection is assured at least in what are called civil rights. The basis of representation is fixed on the number of voters, so that if colored citizens are not allowed to vote they will not by their numbers contribute to representative power, and one voter in South Carolina will not be able to neutralize two voters in Massachusetts or Illinois. Ex-rebels who had taken an oath to support the Constitution of the United States are excluded from office, national or state. The national debt is guaranteed, while the rebel debt and all claim for slaves are annulled. But all these essential safeguards are rudely rejected by the President. . . .

And now that I may give practical direction to these remarks, let me tell you plainly what must be done. In the first place, Congress must be sustained in its conflict with the One Man Power, and in the second place, ex-rebels must not be restored to power. Bearing these two things in mind the way will be easy. Of course, the constitutional amendment must be adopted. As far as it goes, it is well; but it does not go far enough. More must be done. Impartial suffrage must be established. A homestead must be secured to every freedman, if in no other way, through the pardoning power. If to these is added Education, there will be a new order of things, with liberty of the press, liberty of speech and liberty of travel, so that Wendell Phillips may speak freely in Charleston or Mobile. . . . Our present desires may be symbolized by four “E’s,” standing for Emancipation, Enfranchisement, Equality and Education. Let these be secured and all else will follow. . . .