Historic Document

Boston and Busing (1999)

Michael Patrick McDonald | 1999

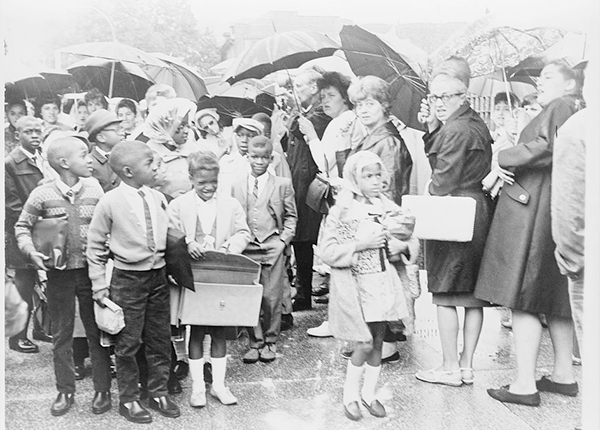

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection

Summary

All Souls is the Irish-American, anti-violence activist Michael Patrick McDonald’s memoir of growing up amidst family trauma and dislocation in the turbulent and changing neighborhood of South Boston. This passage narrates the author’s youthful experiences after federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered the schools of Boston’s disproportionately Black Roxbury neighborhood integrated with those of traditionally Irish South Boston in 1974. The case, Morgan v. Hennigan, was brought by Black parents and children with the assistance of the NAACP under the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, which guarantees “equal protection of the laws.”

In 1954, the Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, holding that school segregation was inconsistent with the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of equality. Following the Court’s second ruling in Brown, requiring that desegregation proceed “with all deliberate speed,” school desegregation advocates faced the practical challenge of ending school segregation on the ground. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, black parents began to challenge segregation in states that did not have segregation laws on the books, alleging that state and local authorities manipulated pupil assignments, attendance zones, district lines and other factors to segregate schoolchildren by race. That gave rise to heated debates – political and constitutional – over school busing as a means of advancing racial integration.

Selected by

Christopher Brooks

Professor of History, East Stroudsburg University

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Document Excerpt

Ma’s tunes on the accordion started to be all about the busing. She played them at rallies, sit-ins, and fundraisers for the struggle, all over Southie. The songs sounded like a lot of the Irish rebel songs we grew up with . . . . The Black and Tans, the murderous regiments who’d wreaked havoc on Ireland on behalf of the English Crown, became the Tactical Police Force (TPF), the special police force that was turning our town into a police state . . . . That’s why we hated Ted Kennedy; he’d sided with the busing took and was seen as the biggest traitor of all, being from the most important Irish family in America. . . .

The English themselves weren’t completely absent from our struggle. They ran the Boston Globe and were behind the whole thing. My friends and I started stealing stacks of the Globe left outside supermarkets in the early mornings. . . . That’s when I found out the Globe was the enemy. We tried to sell it in Southie, but too many people said they wouldn’t read that liberal piece of trash if it was free. . . . He showed me the names of the Globe’s owners and editors: ‘Winship, Taylor. All WASPS,” he said . . . .’

That September, Ma let us skip the first week of school. The whole neighborhood was boycotting school. City Councilor Louise Day Hicks and her bodyguard with the bullhorn, Jimmy Kelly, were telling people to keep their kids home. . . . It was still warm outside and we wanted to join the crowds that were just then lining the streets to watch the busloads of black kids come into Southie. The excitement built as police helicopters hovered just above our third floor windows, police in riot gear stood guard on the rooftops of Old Colony . . . . Ma said okay, and we ran up to Darius Court, along the busing route, where in simpler times we’d watched the neighborhood St. Paddy’s Day parade.

We saw a line of yellow buses like there was no end to them. I couldn’t see any black faces though, and I was looking for them. Some people around me started to cry when they finally got a glimpse of the buses through the crowd. One woman made the sign of the cross and a few others copied her. ‘I never thought I’d see the day come,’ said an old woman next to me. . . .

Every day I felt the pride of rebellion. The helicopters above my bedroom window woke me each morning for school, and my friends and I would plan to pass by the TPF on the corners so we could walk around them and give them hateful looks. Ma and the nuns at St. Augustine’s told me it was wrong to hate the blacks for any of this. But I had to hate someone, and the police were always fracturing some poor neighbor’s skull or taking teenagers over to the beach at night to beat them senseless. . . .

The signs at the marches were starting to change. Instead of Restore Our Alienated Rights and Welcome to Moscow America, more and more now I saw Bus the N's Back to Africa, and one even said KKK. . . . I had always heard stories from Grandpa about a time when the Ku Klux Klan burned Irish Catholics out of their homes in America. . . .

Someone popped up his stereo speakers in a project window, blasting a favorite at the time: “Fight the Power” by the Isley Brothers. . . . Everyone sang along to “Fight the Power.” The teenagers in Southie still listened only to black music. . . . I never heard anyone listening to rock and roll in Old Colony. . . Rock and roll was for rich suburban people with long hair and dirty clothes. Mary had a . . . tongue painted on her bedroom wall, but that was for Rufus and Chaka Khan; it was okay to like them. Of course no one called it black music . . . but I knew the Isley Brothers were black because I’d seen them on “Soul Train.” But that didn’t bother anyone in the crowd; what mattered was that the Isley Brothers were singing about everything we were watching in our streets right now, the battle between us and the law. . . .