Historic Document

The Politics (ca. 350 BC)

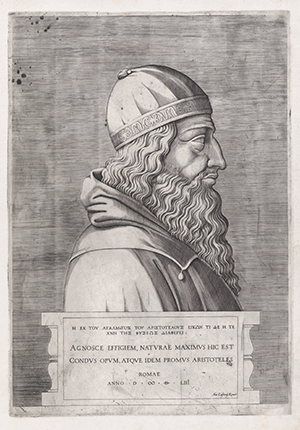

Aristotle | 350 BC

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1941

Summary

Aristotle son of Nicomachus (384-22 BC) was the author of The Politics and a great many other philosophical works. He agreed with Plato that a republic could only be preserved in a small territory with a small population. Those in the Founding generation who consulted Aristotle studied his analysis of territorial size, population, and stasis, with particular emphasis on the threat to republican institutions posed by faction. This was the context for James Madison’s creative solution to confronting the problem of faction in Federalist 10.

Selected by

Paul Rahe

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Document Excerpt

The Politics, Book II

[W]e come to consider . . . the different number of governments which there are, and what they are; and first, what are their excellencies: for when we have determined this, their defects will be evident enough.

It is evident that every form of government . . . must contain a supreme power over the whole state, and this supreme power must necessarily be in the hands of one person, or a few, or many; and when either of these apply their power for the common good, such states are well-governed; but when the interest of the one, the few, or the many who enjoy this power is alone consulted, then ill . . . . We usually call a state which is governed by one person for the common good, a kingdom; one that is governed by more than one, but by only a few, an aristocracy; either because the government is in the hands of the most worthy citizens, or because it is the best form for the city and its inhabitants. When the citizens at large govern for the public good, it is called a state [or a polity] . . . .

Now the corruptions attending each of these governments are these; a kingdom may degenerate into a tyranny, an aristocracy into an oligarchy, and a state [or polity] into a democracy. Now a tyranny is a monarch where the good of one man is the object of government, an oligarchy only the rich, and a democracy only the poor; but neither of them have a common good in view.

The Politics, Book V.2

Since we are inquiring into the causes of seditions and revolutions in governments, we must begin entirely with the first principles from whence they arise. Now these, so to speak, are nearly three in number; which we must first distinguish in general from each other, and endeavour to show in what situation people are who begin a sedition; and for what causes; and thirdly, what are the beginnings of political troubles and mutual quarrels with each other. Now that cause which of all others most universally inclines men to desire to bring about a change in government is that which I have already mentioned; for those who aim at equality will be ever ready for sedition, if they see those whom they esteem their equals possess more than they do, as well as those also who are not content with equality but aim at superiority, if they think that while they deserve more than, they have only equal with, or less than, their inferiors. Now, what they aim at may be either just or unjust; just, when those who are inferior are seditious, that they may be equal; unjust, when those who are equal are so, that they may be superior. These, then, are the situations in which men will be seditious: the causes for which they will be so are profit and honour; and their contrary: for, to avoid dishonour or loss of fortune by mulcts, either on their own account or their friends, they will raise a commotion in the state. The original causes which dispose men to the things which I have mentioned are, taken in one manner, seven in number, in another they are more; two of which are the same with those that have been already mentioned: but influencing in a different manner; for profit and honour sharpen men against each other; not to get the possession of them for themselves (which was what I just now supposed), but when they see others, some justly, others unjustly, engrossing them. The other causes are haughtiness, fear, eminence, contempt, disproportionate increase in some part of the state. There are also other things which in a different manner will occasion revolutions in governments; as election intrigues, neglect, want of numbers, a too great dissimilarity of circumstances.

The Politics Book V.12

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates is introduced treating upon the changes which different governments are liable to: but his discourse is faulty; for he does not particularly mention what changes the best and first governments are liable to; for he only assigns the general cause, of nothing being immutable, but that in time everything will alter ... he conceives that nature will then produce bad men, who will not submit to education, and in this, probably, he is not wrong; for it is certain that there are some persons whom it is impossible by any education to make good men; but why should this change be more peculiar to what he calls the best-formed government, than to all other forms, and indeed to all other things that exist? and in respect to his assigned time, as the cause of the alteration of all things, we find that those which did not begin to exist at the same time cease to be at the same time; so that, if anything came into beginning the day before the solstice, it must alter at the same time. Besides, why should such a form of government be changed into the Lacedaemonian? for, in general, when governments alter, they alter into the contrary species to what they before were, and not into one like their former. And this reasoning holds true of other changes; for he says, that from the Lacedaemonian form it changes into an oligarchy, and from thence into a democracy, and from a democracy into a tyranny: and sometimes a contrary change takes place, as from a democracy into an oligarchy, rather than into a monarchy. With respect to a tyranny he neither says whether there will be any change in it; or if not, to what cause it will be owing; or if there is, into what other state it will alter: but the reason of this is, that a tyranny is an indeterminate government; and, according to him, every state ought to alter into the first, and most perfect, thus the continuity and circle would be preserved. But one tyranny often changed into another; as at Syria, from Myron’s to Clisthenes’; or into an oligarchy, as was Antileo’s at Chalcas; or into a democracy, as was Gelo’s at Syracuse; or into an aristocracy, as was Charilaus’s at Lacedaemon, and at Carthage. An oligarchy is also changed into a tyranny; such was the rise of most of the ancient tyrannies in Sicily; at Leontini, into the tyranny of Panaetius; at Gela, into that of Cleander; at Rhegium into that of Anaxilaus; and the like in many other cities. It is absurd also to suppose, that a state is changed into an oligarchy because those who are in power are avaricious and greedy of money, and not because those who are by far richer than their fellow citizens think it unfair that those who have nothing should have an equal share in the rule of the state with themselves, who possess so much - for in many oligarchies it is not allowable to be employed in money-getting, and there are many laws to prevent it. But in Carthage, which is a democracy, money-getting is creditable, and yet their form of government remains unaltered. It is also absurd to say, that in an oligarchy there are two cities, one of the poor and another of the rich; for why should this happen to them more than to the Lacedaemonians, or any other state where all possess not equal property, or where all are not equally good? for though no one member of the community should be poorer than he was before, yet a democracy might nevertheless change into an oligarchy; if the rich should be more powerful than the poor, and the one too negligent, and the other attentive: and though these changes are owing to many causes, yet he mentions but one only, that the citizens become poor by luxury, and paying interest-money; as if at first they were all rich, or the greater part of them: but this is not so, but when some of those who have the principal management of public affairs lose their fortunes, they will endeavour to bring about a revolution; but when others do, nothing of consequence will follow, nor when such states do alter is there any more reason for their altering into a democracy than any other. Besides, though some of the members of the community may not have spent their fortunes, yet if they share not in the honours of the state, or if they are ill-used and insulted, they will endeavour to raise seditions, and bring about a revolution, that they may be allowed to do as they like; which, Plato says, arises from too much liberty. Although there are many oligarchies and democracies, yet Socrates, when he is treating of the changes they may undergo, speaks of them as if there was but one of each sort.

The Politics, Book VIII.1

No one can doubt that the magistrate ought greatly to interest himself in the care of youth; for where it is neglected it is hurtful to the city, for every state ought to be governed according to its particular nature; for the form and manners of each government are peculiar to itself; and these, as they originally established it, so they usually still preserve it. For instance, democratic forms and manners a democracy; oligarchic, an oligarchy: but, universally, the best manners produce the best government. Besides, as in every business and art there are some things which men are to learn first and be made accustomed to, which are necessary to perform their several works; so it is evident that the same thing is necessary in the practice of virtue. As there is one end in view in every city, it is evident that education ought to be one and the same in each; and that this should be a common care, and not the individual’s, as it now is, when every one takes care of his own children separately; and their instructions are particular also, each person teaching them as they please; but what ought to be engaged in ought to be common to all. Besides, no one ought to think that any citizen belongs to him in particular, but to the state in general; for each one is a part of the state, and it is the natural duty of each part to regard the good of the whole: and for this the Lacedaemonians may be praised; for they give the greatest attention to education, and make it public. It is evident, then, that there should be laws concerning education, and that it should be public.