Section One

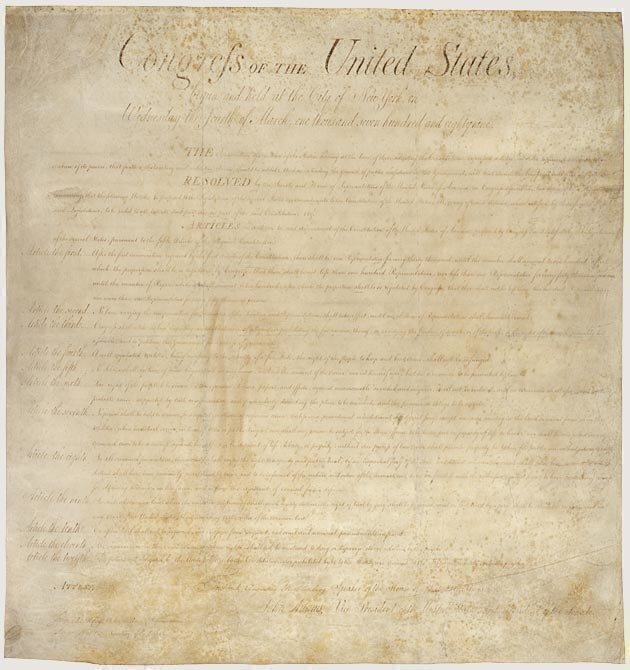

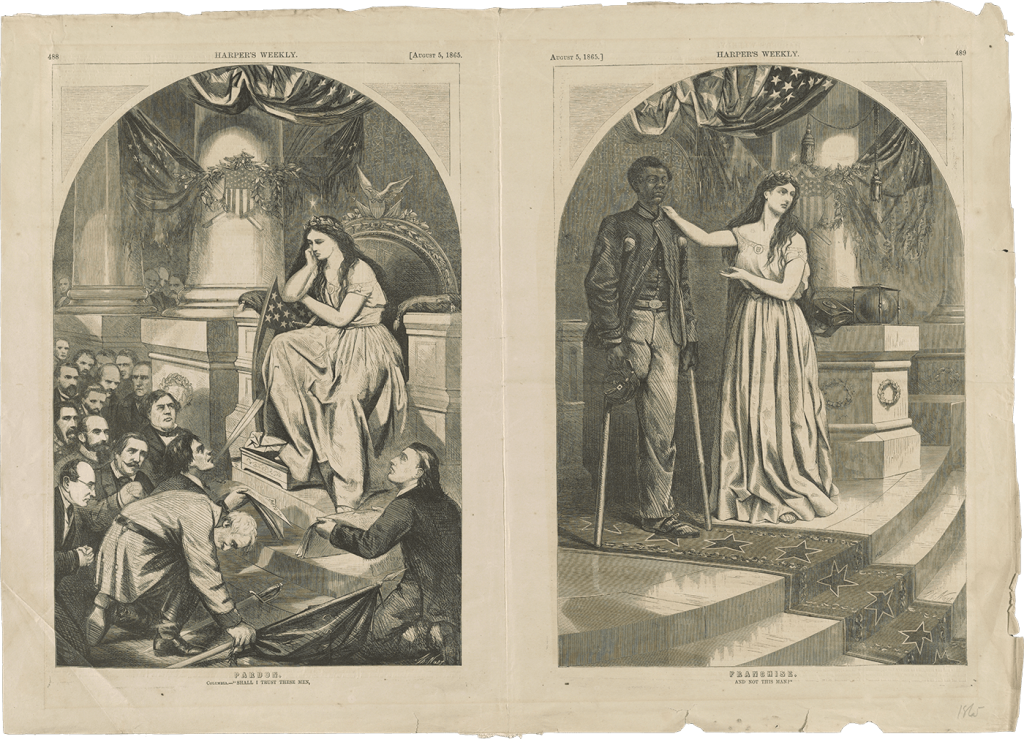

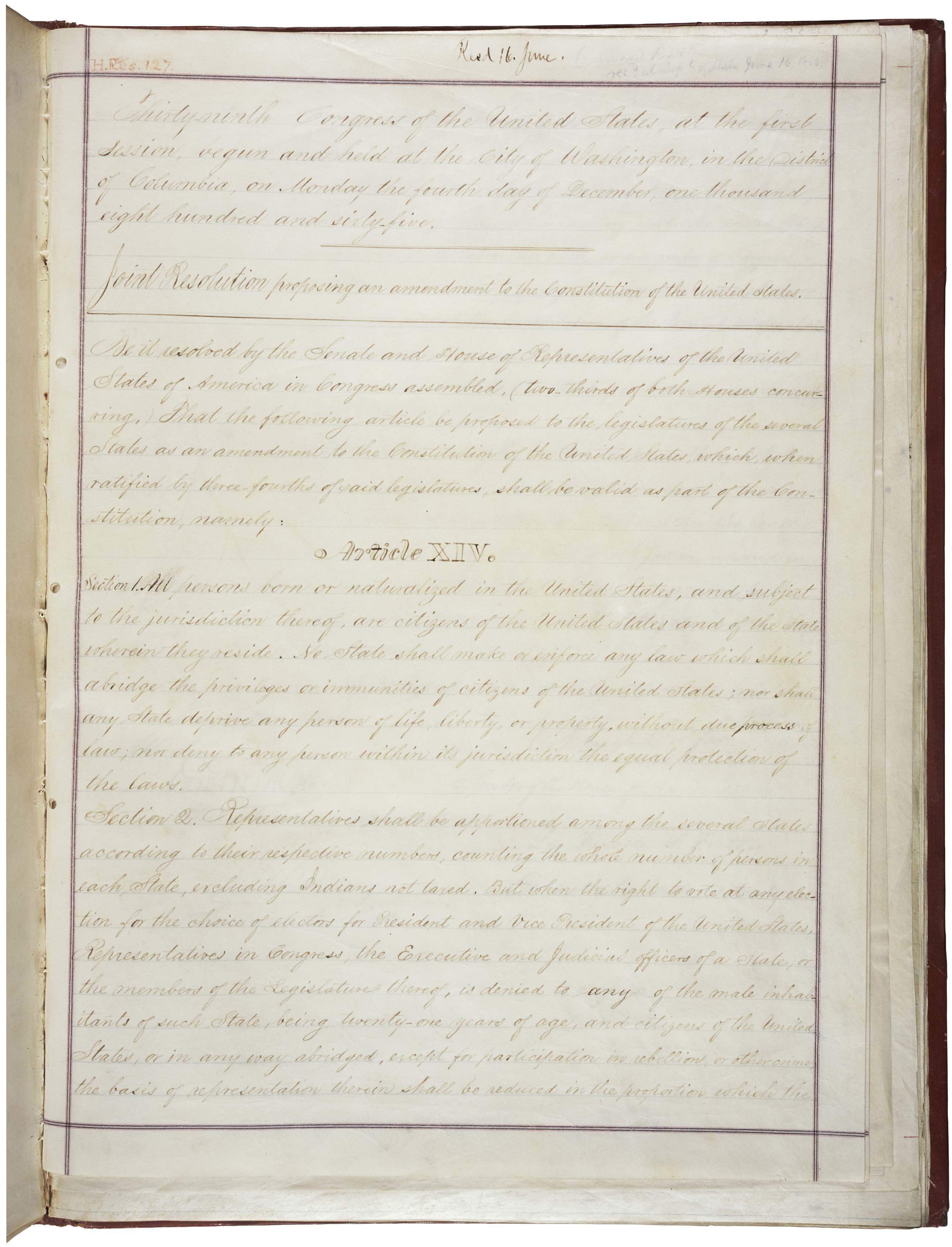

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

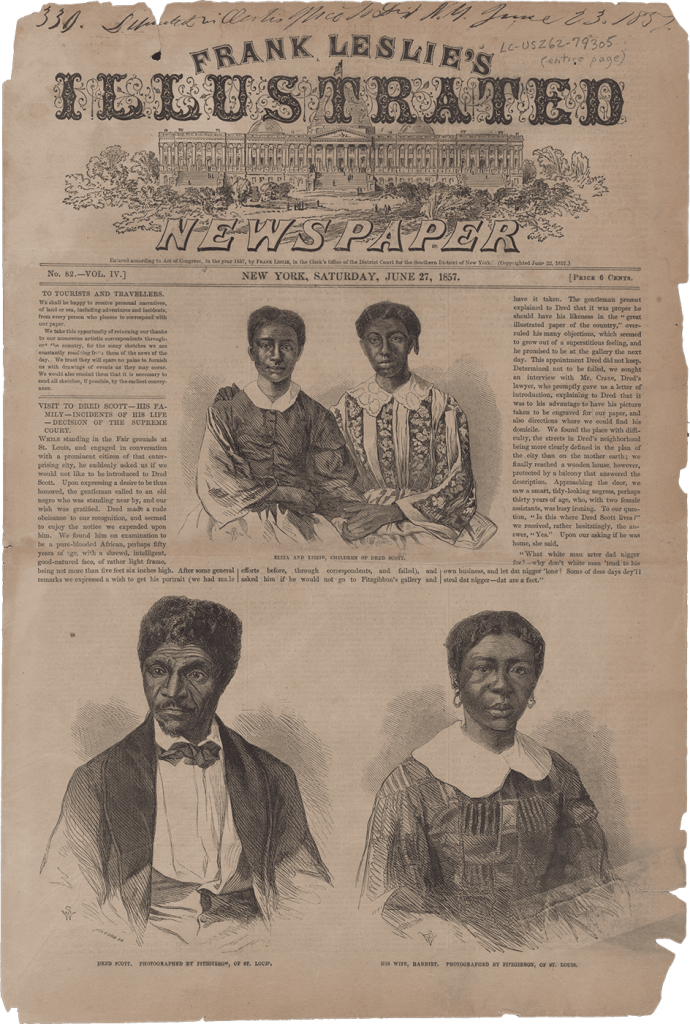

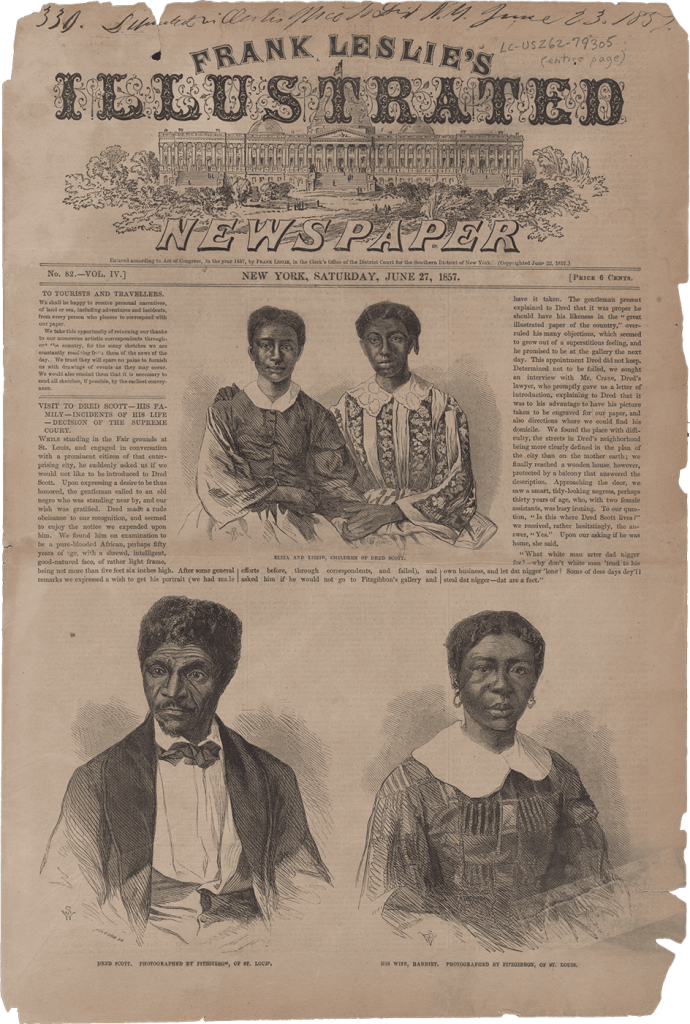

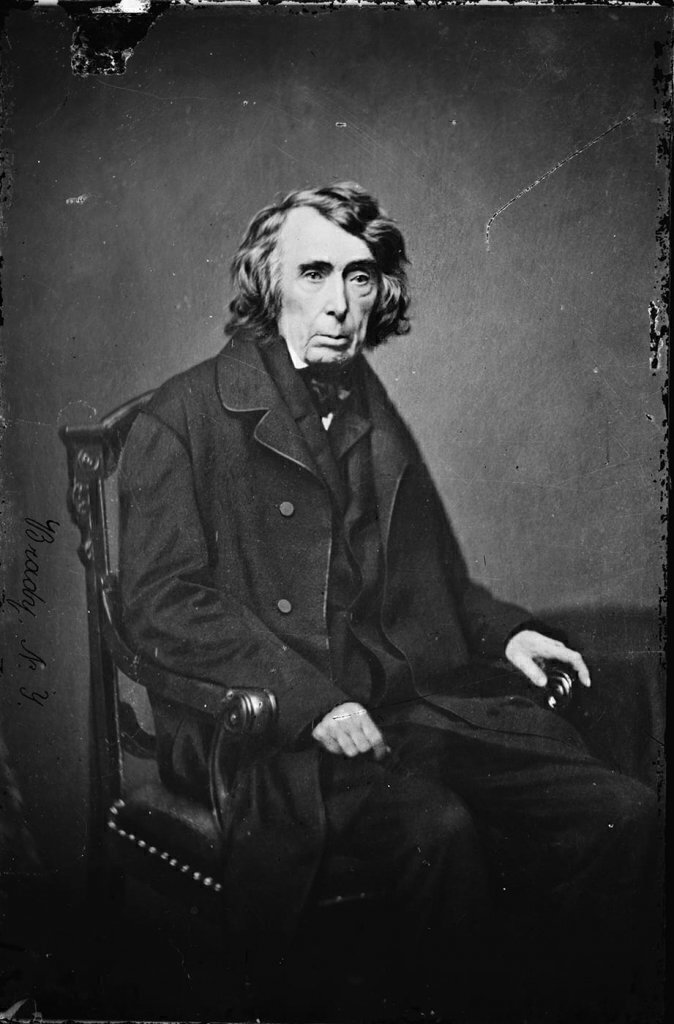

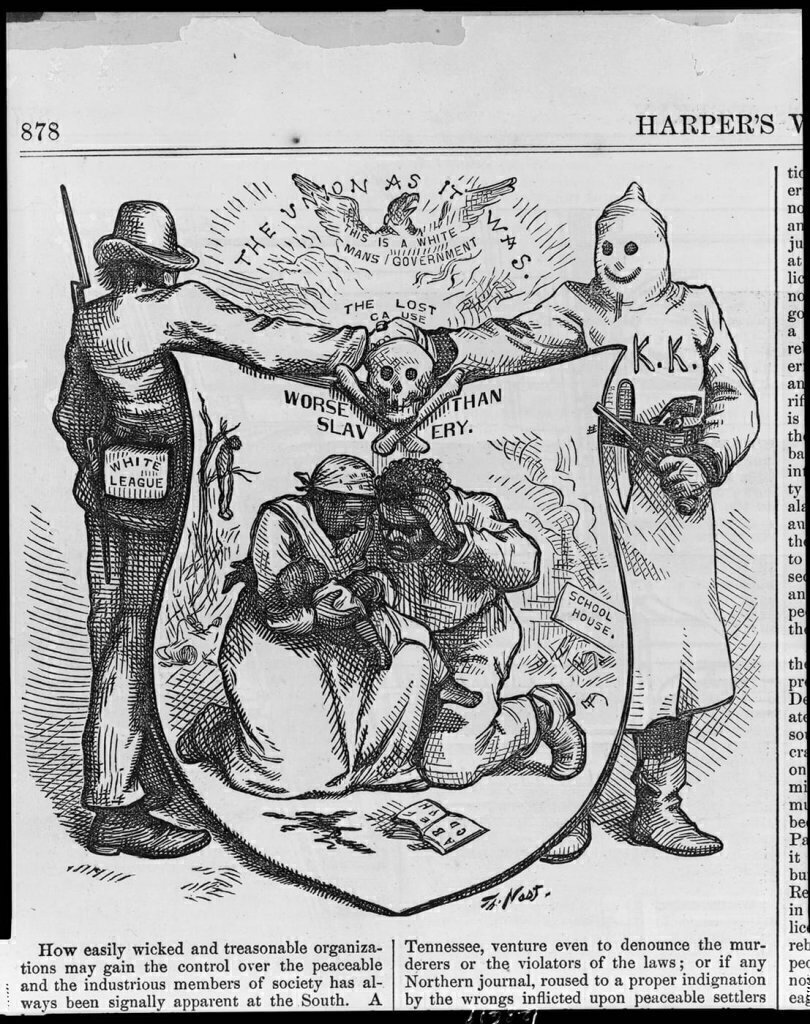

This text, known as the Citizenship Clause, declared that everyone born on American soil is a citizen of the United States. The provision overturned Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) and ended a decades-long debate about whether free black people were American citizens. Finally, natural-born African Americans could lay claim to the promise of equal citizenship.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

This clause demanded that states respect the “privileges or immunities” of U.S. citizens. Originally, the Bill of Rights bound only the national government, not the states. Therefore, states could violate key protections like free speech and religious liberty. Many Southern states did—for example, by banning abolitionist speech in the lead-up to the Civil War.

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law;

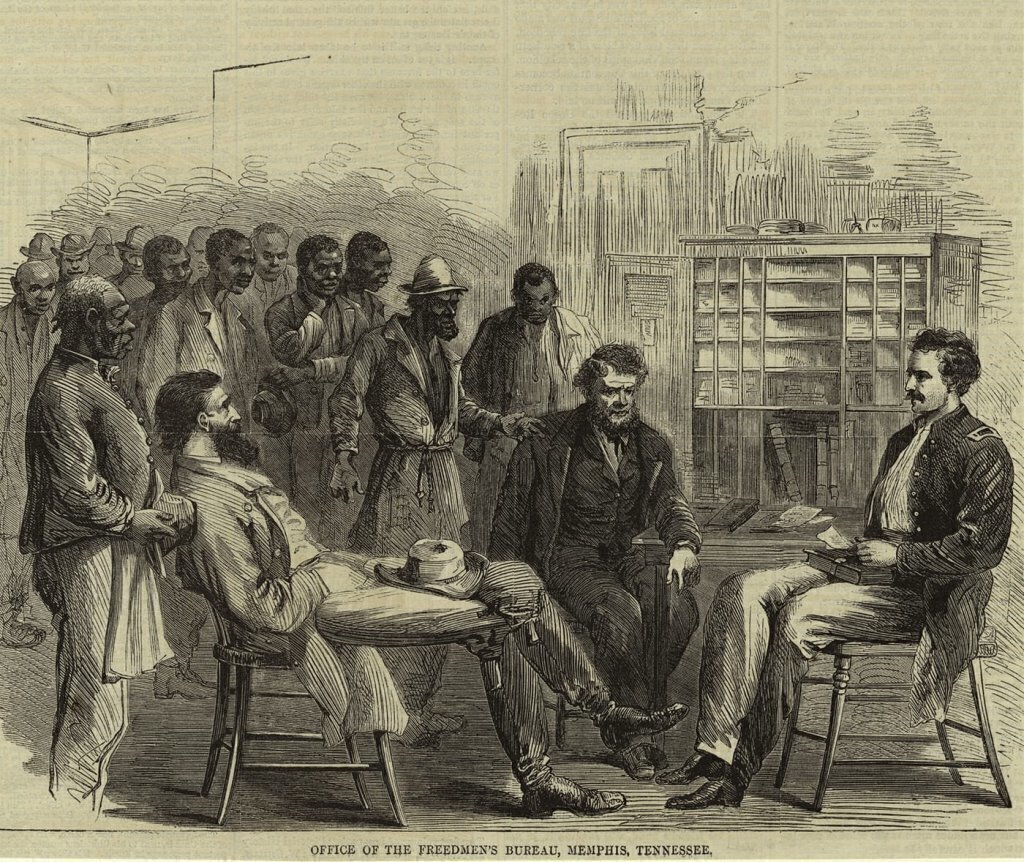

This clause banned states from denying any person due process of law. Without national guarantees in place, Reconstruction Republicans worried that African Americans might not be permitted to enjoy even basic rights. This provision ensured that all people would receive fair treatment from state authorities before any loss of life, liberty, or property.

nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

While seeking safeguards for those formerly enslaved, this part of the amendment reached more broadly, promising “equal protection of the laws” for “any person” in the United States. The original document was silent on the issue of equality, but with this amendment, Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence's promise into the Constitution.

Section Two

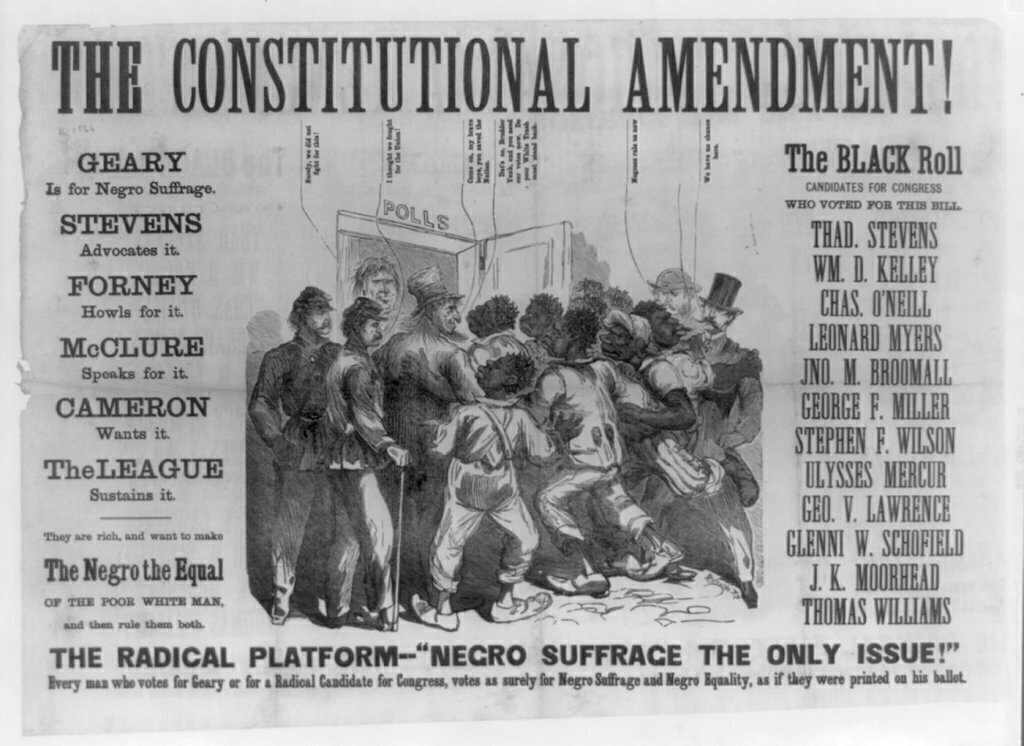

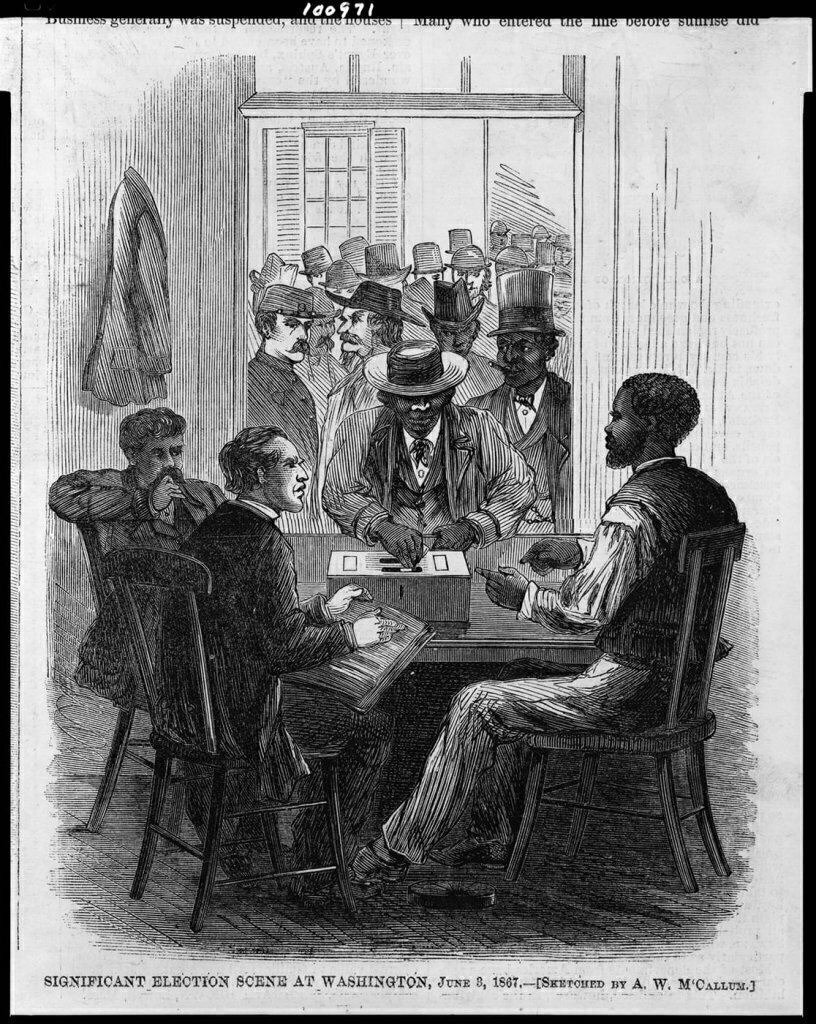

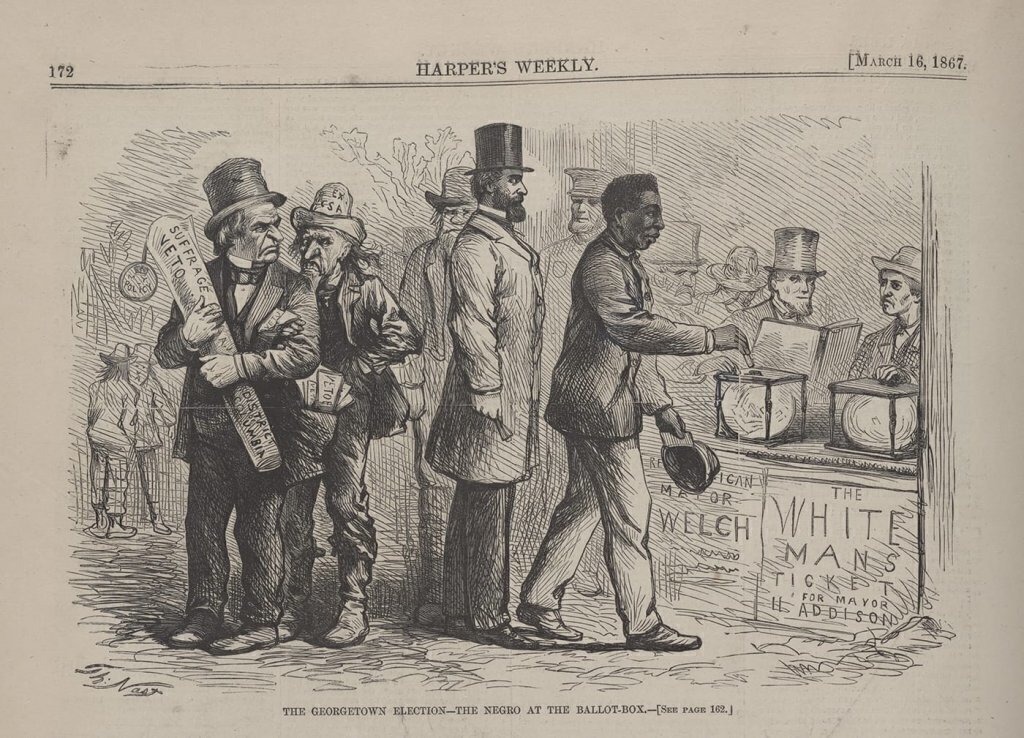

Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

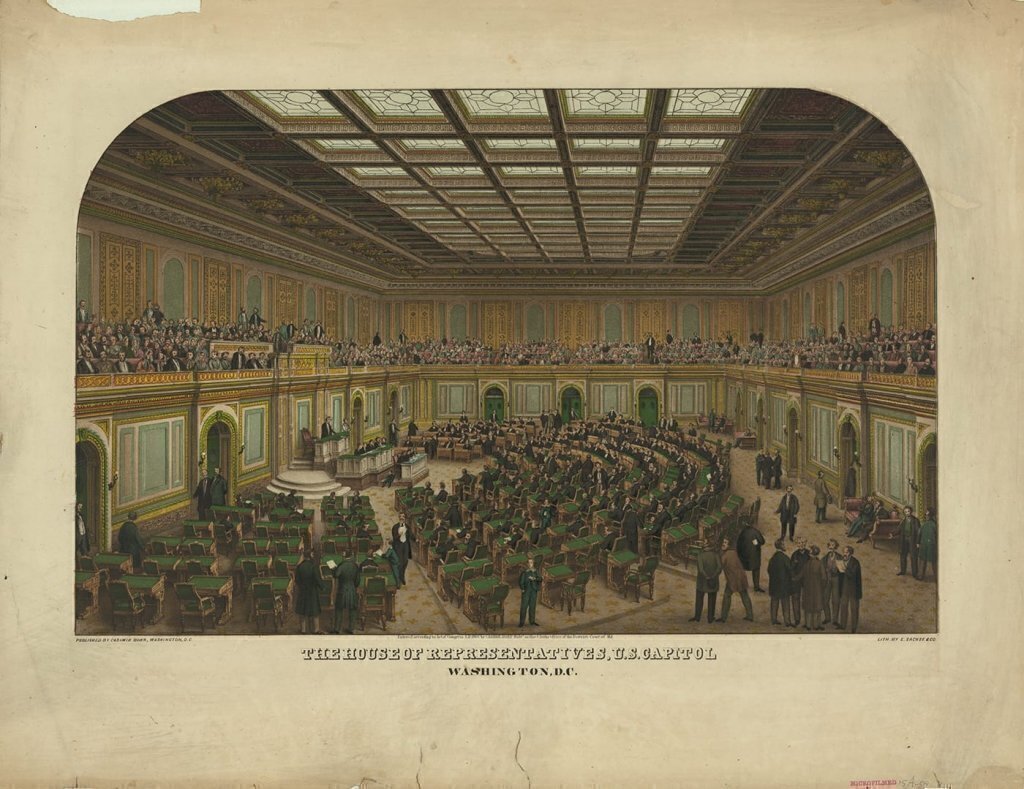

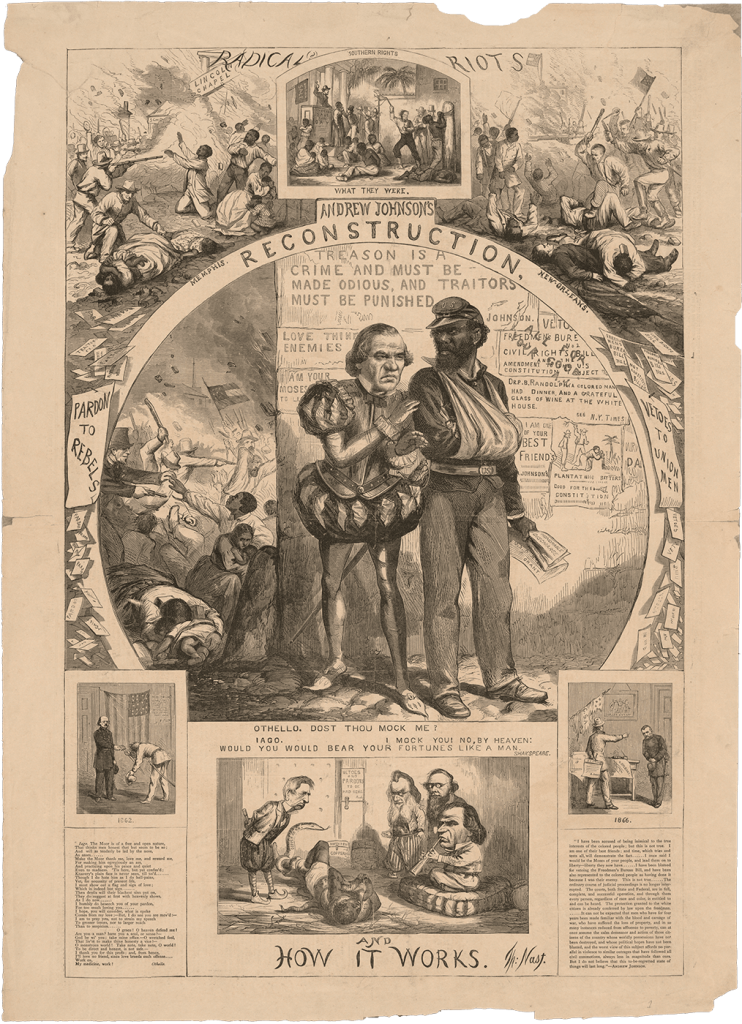

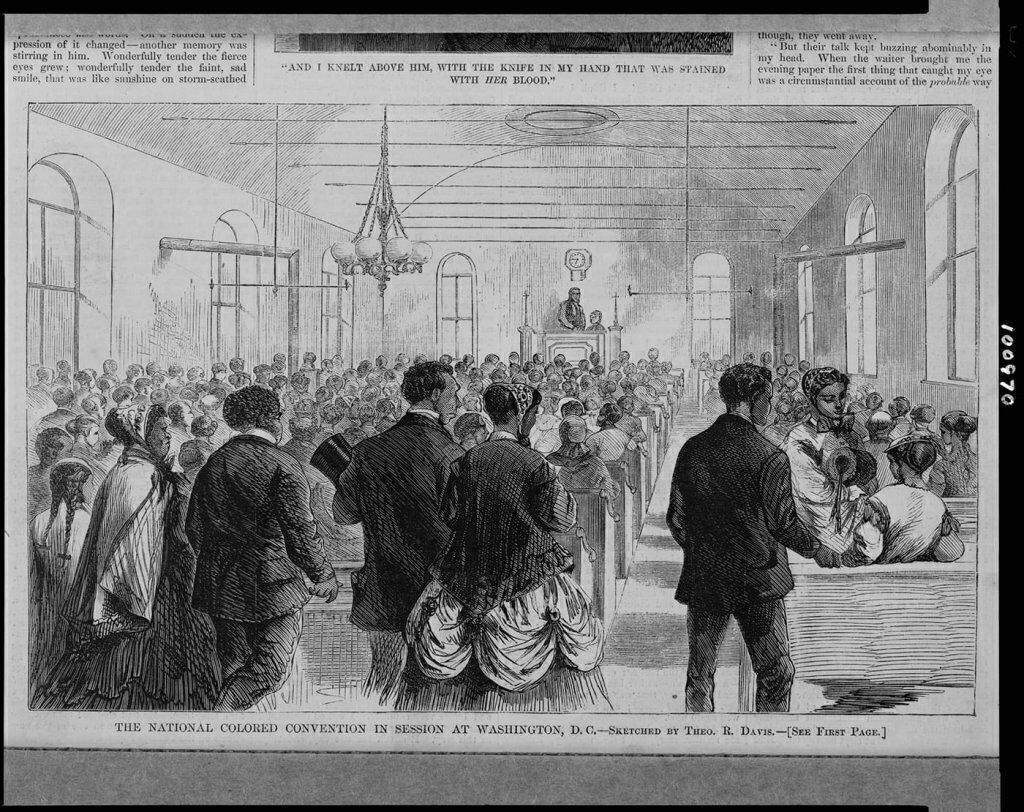

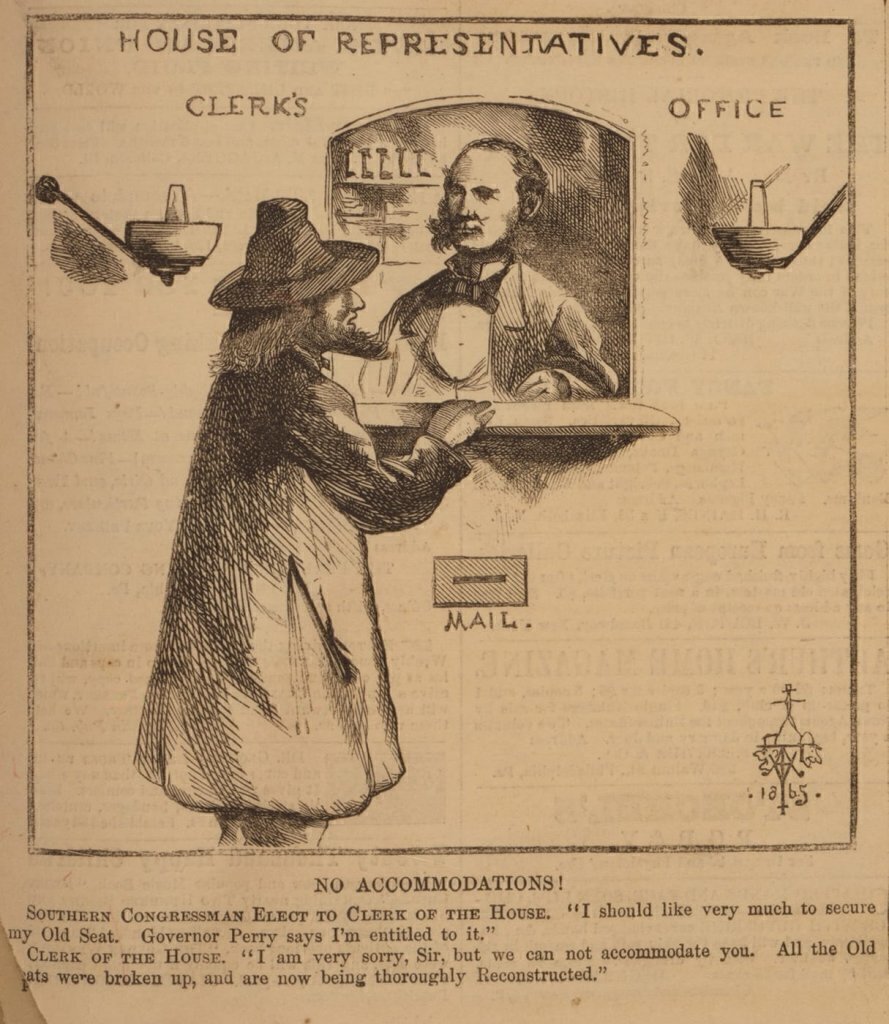

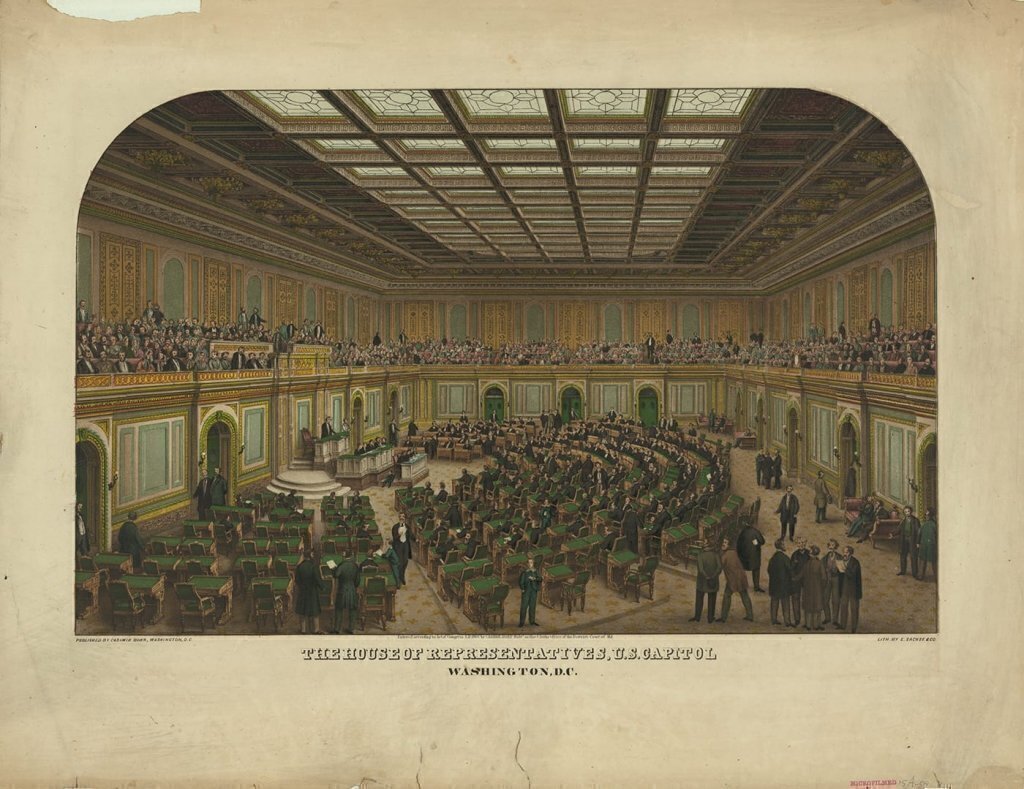

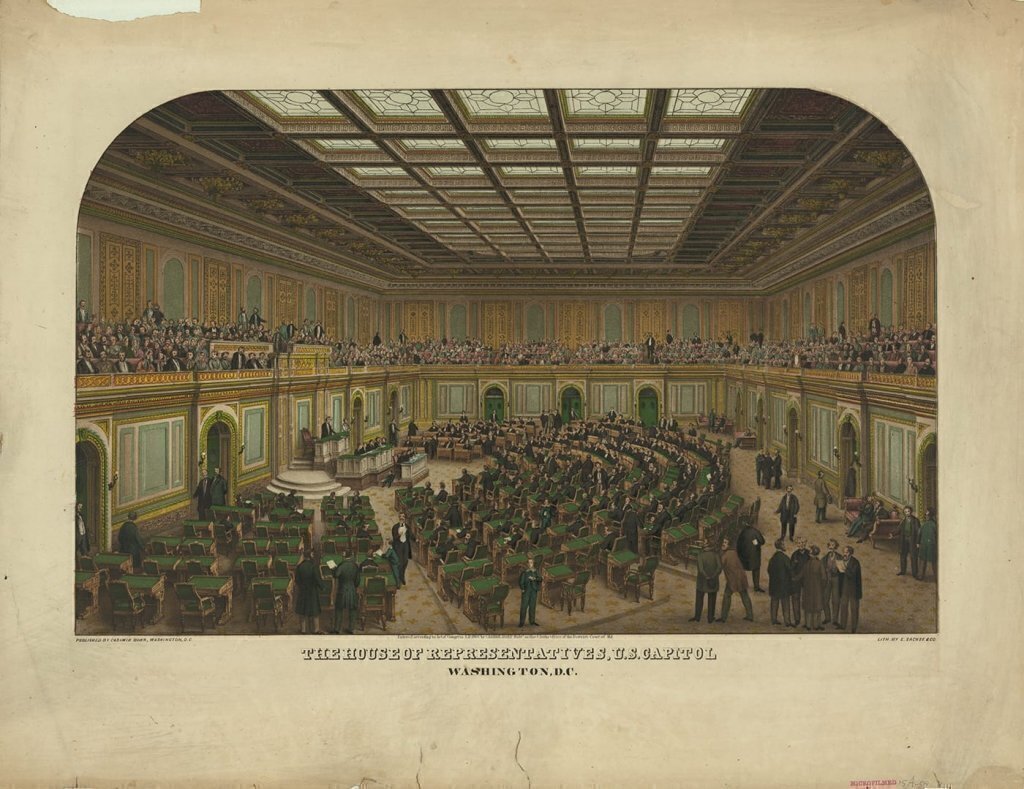

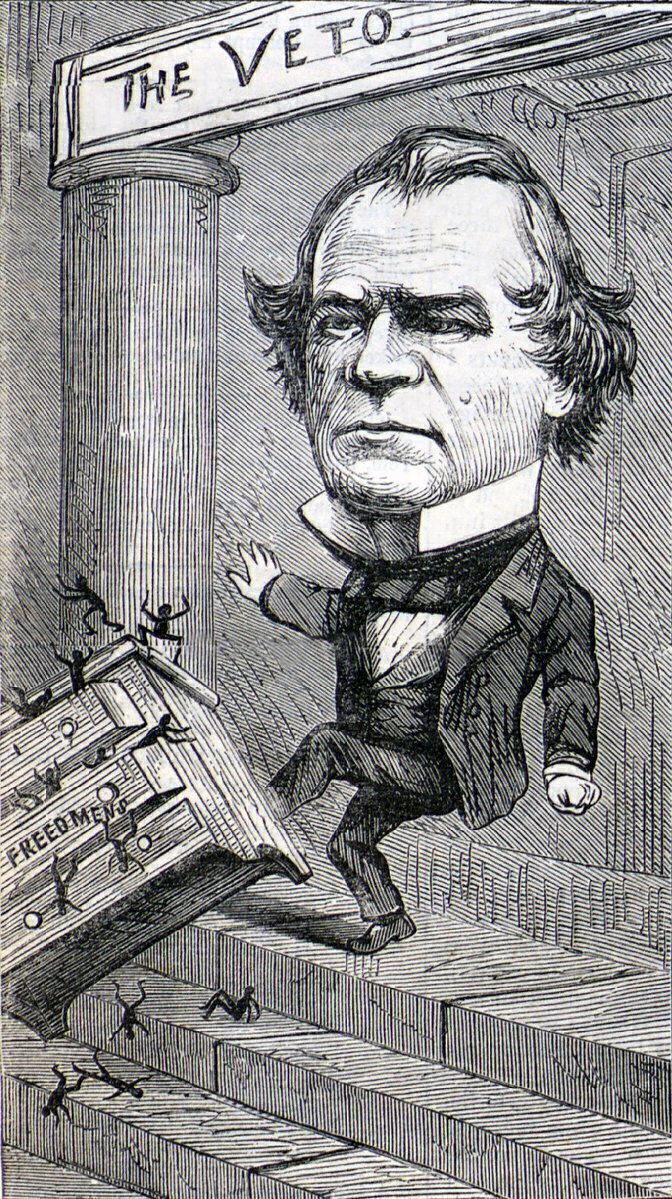

Section Two concerns representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. The original Constitution counted three-fifths of the enslaved population for congressional representation. With the end of slavery, “the whole number of persons” in the ex-Confederate states, including African Americans, would be counted. Reconstruction Republicans feared that this would empower the white South in future Congresses. Section Two addressed this concern by reducing representation in the House for any state that denied black men the right to vote.

Section Three

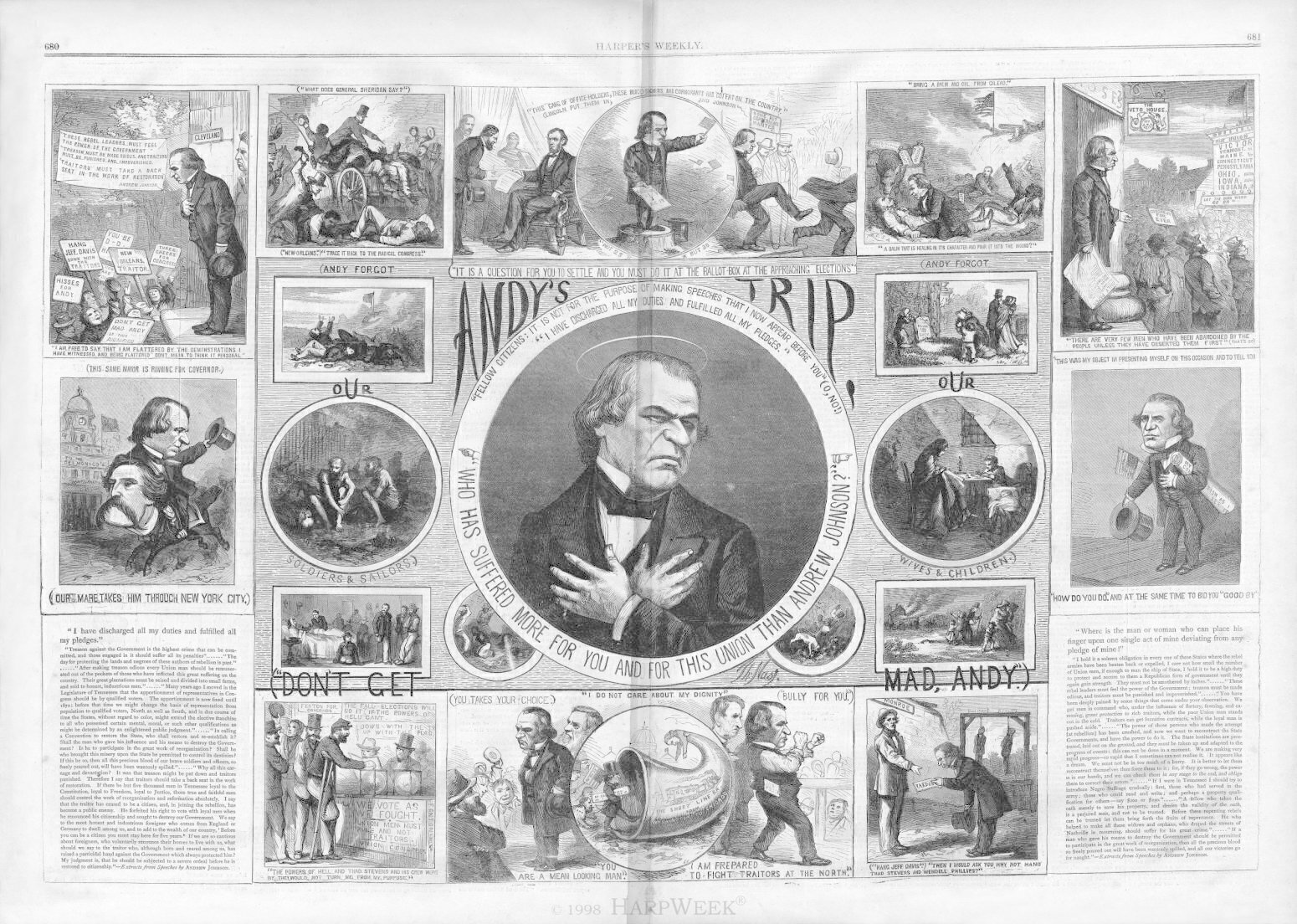

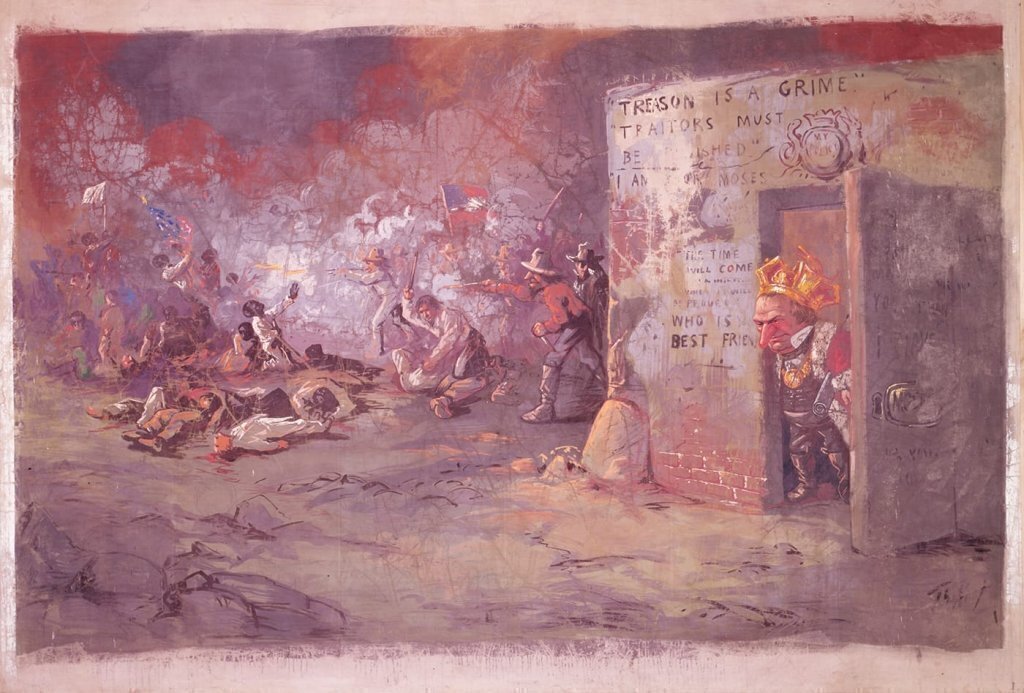

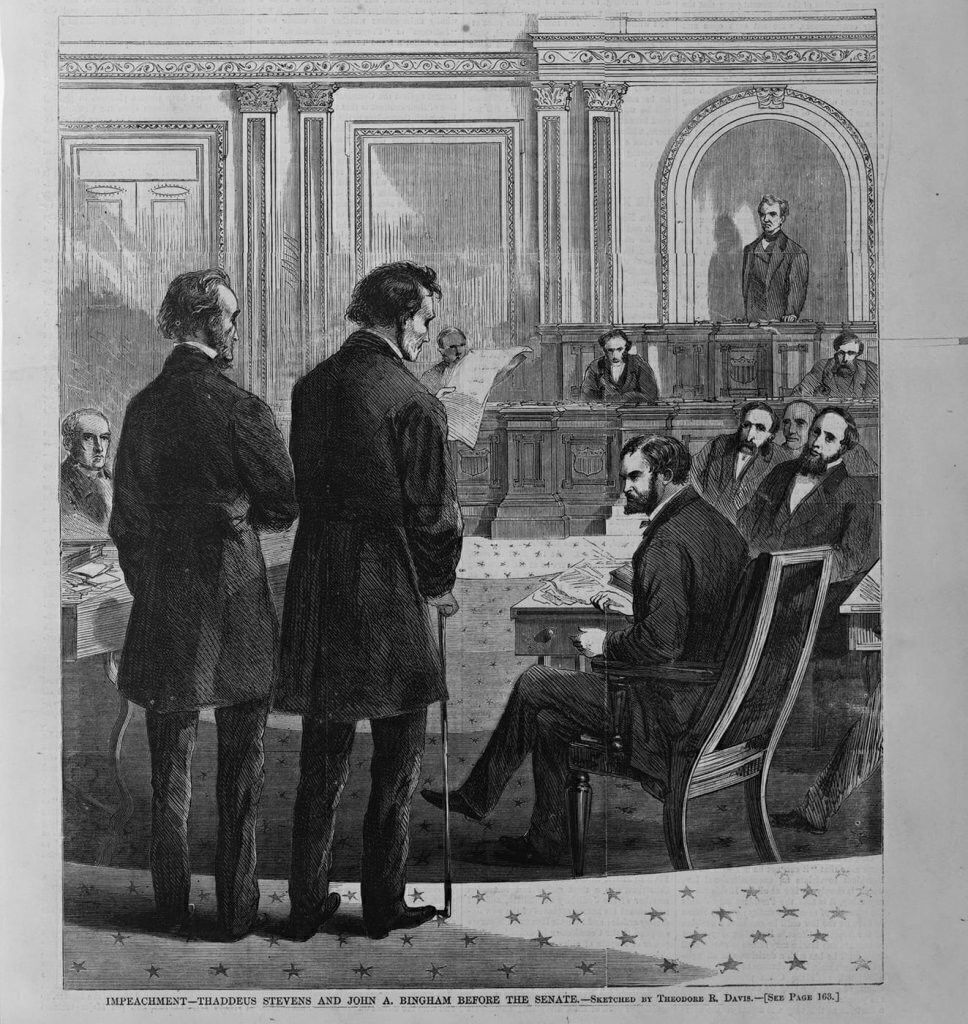

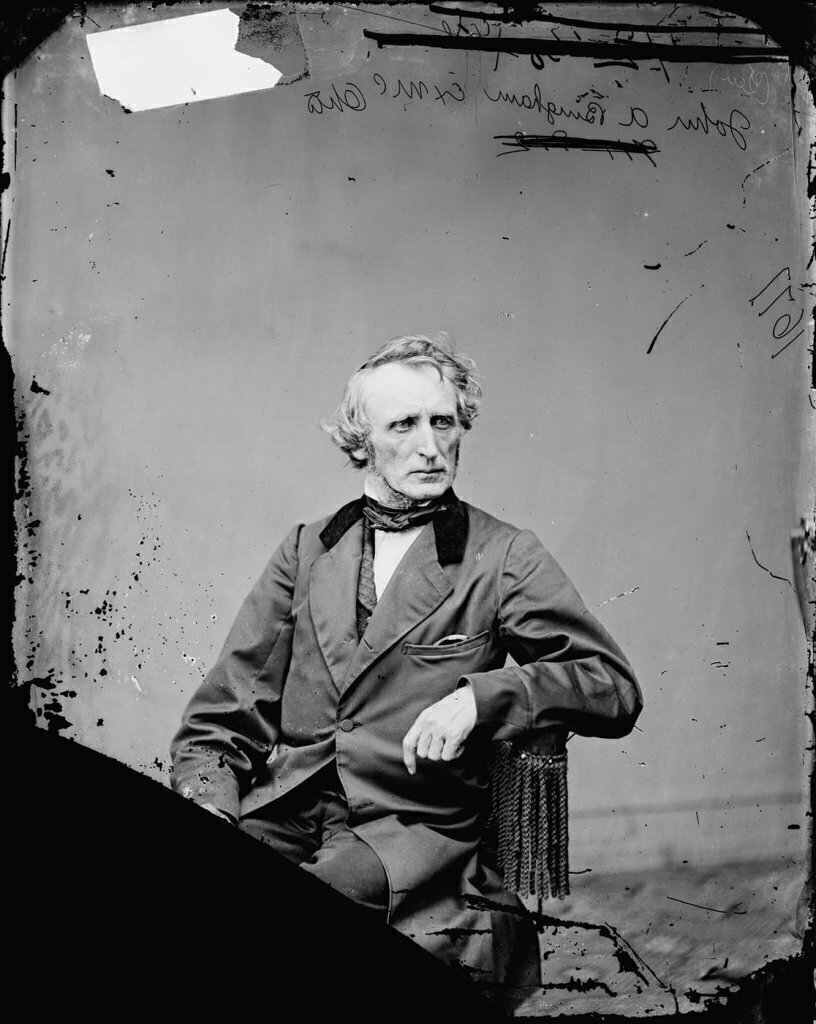

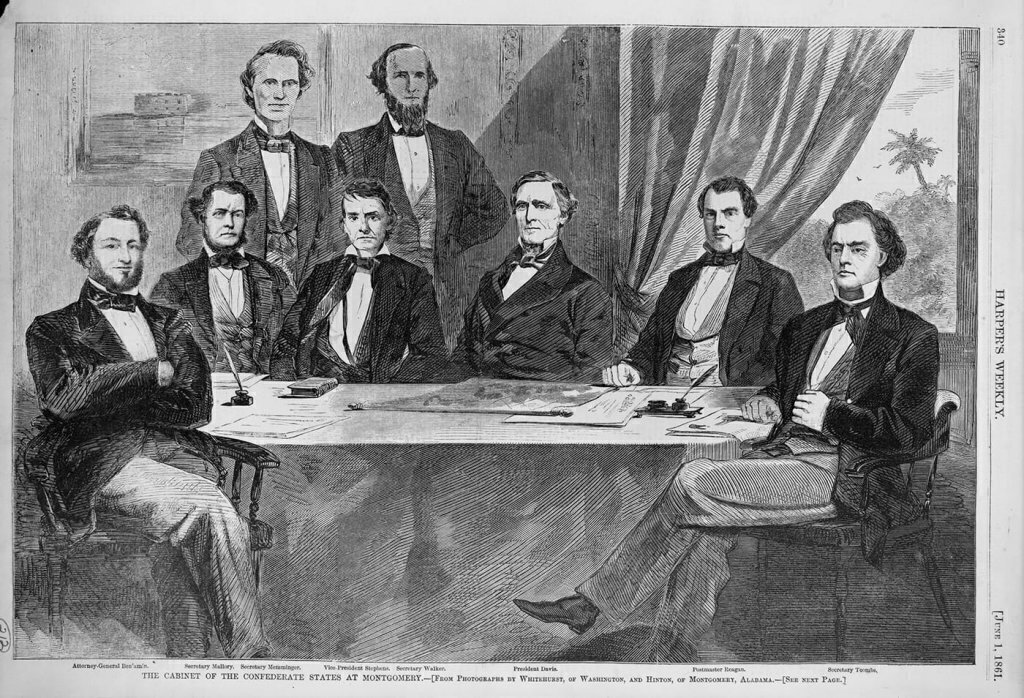

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

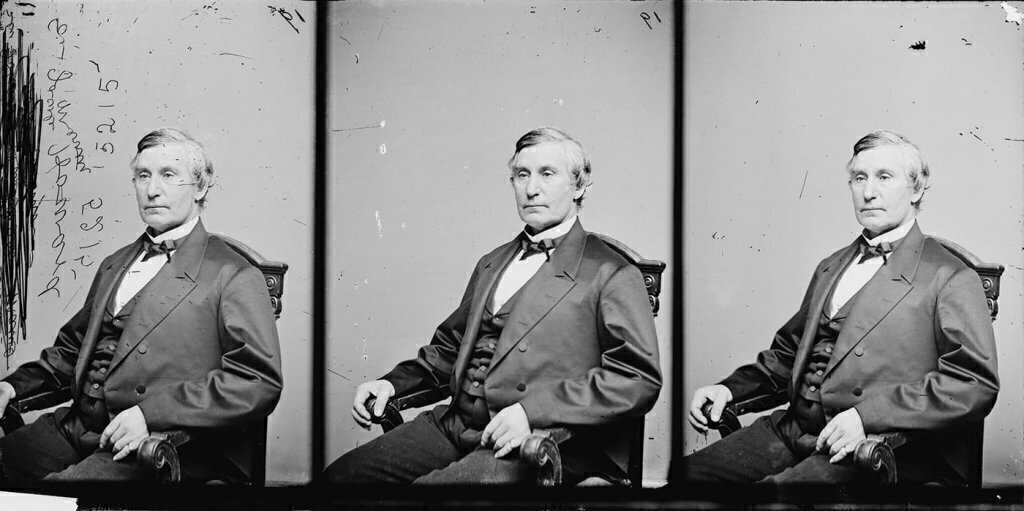

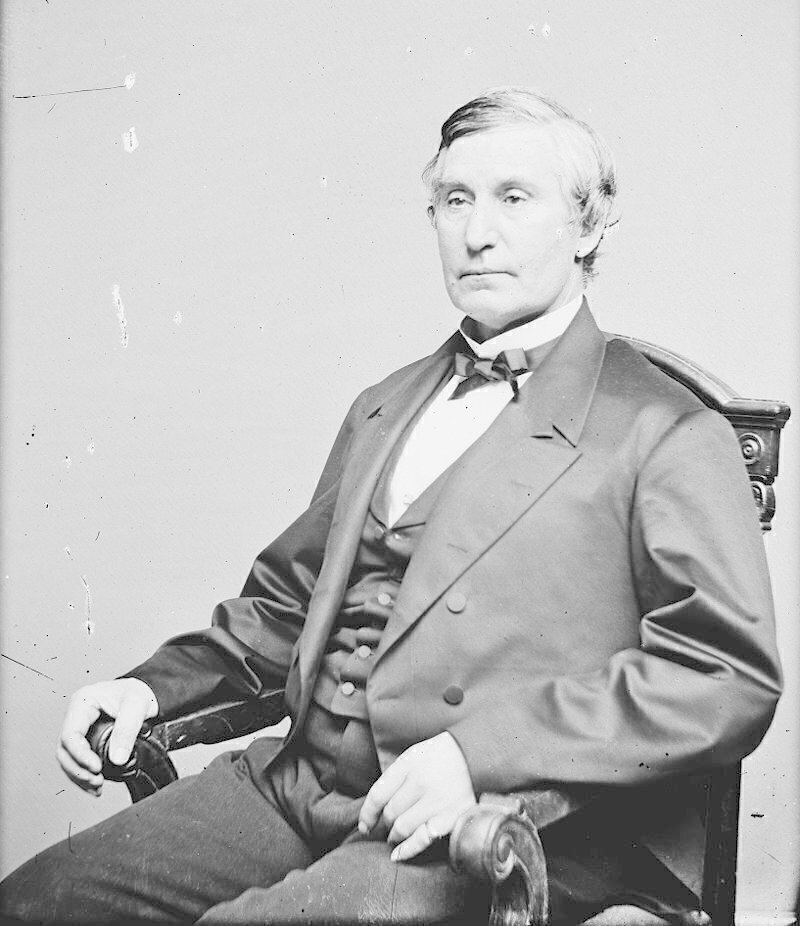

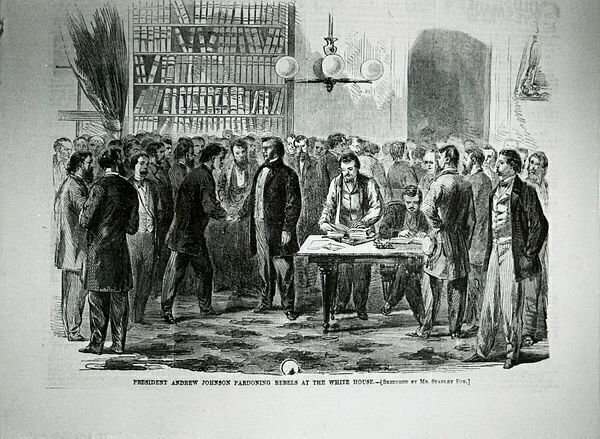

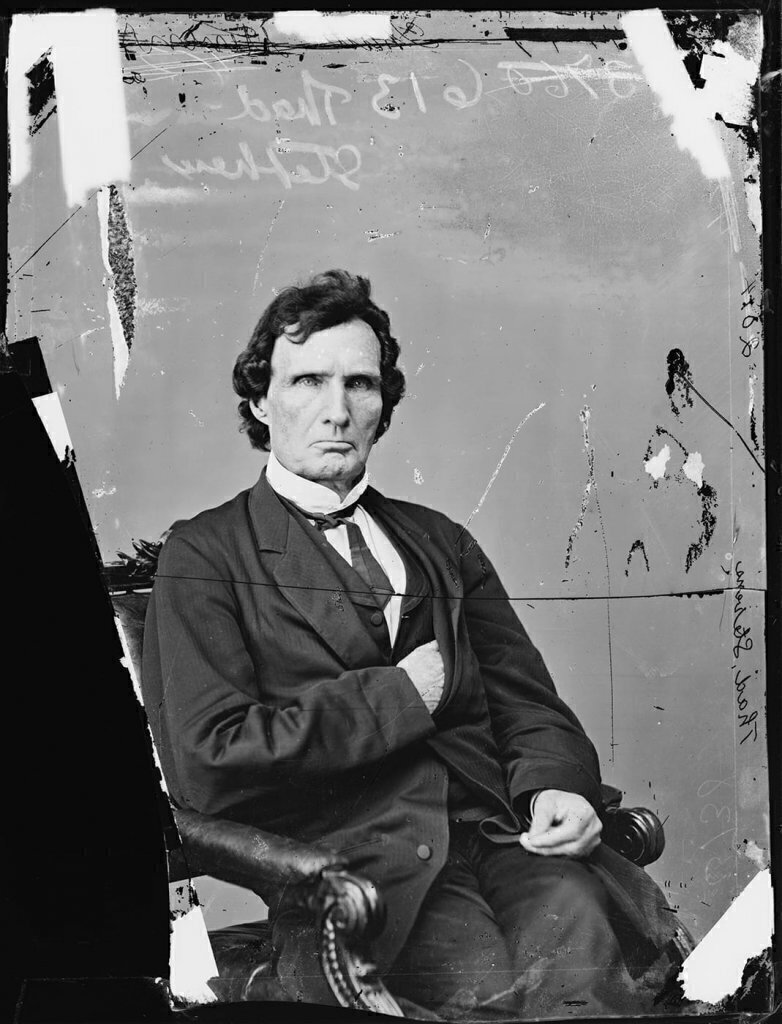

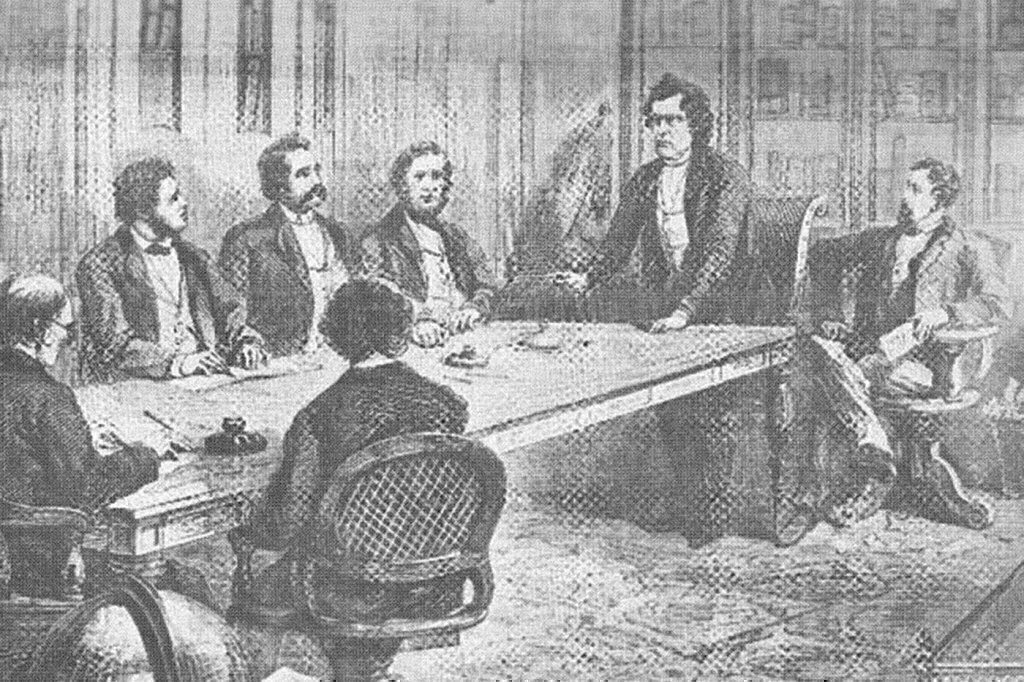

Section Three ended office-holding rights for high-ranking ex-Confederates. It also granted Congress the power to lift these restrictions. Since Republicans feared a return to power for ex-Confederate leaders, Congress had debated a range of issues, such as which former rebels to punish and how broadly any punishment should sweep. The final text had a narrow scope.

Section Four

The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section Four served two purposes. First, it protected the national debt from attempts by future Democratic Congresses to reject paying it. Second, it prohibited the United States from paying any of the debt incurred by the Confederacy—including claims made over the loss of emancipated slaves.

Section Five

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

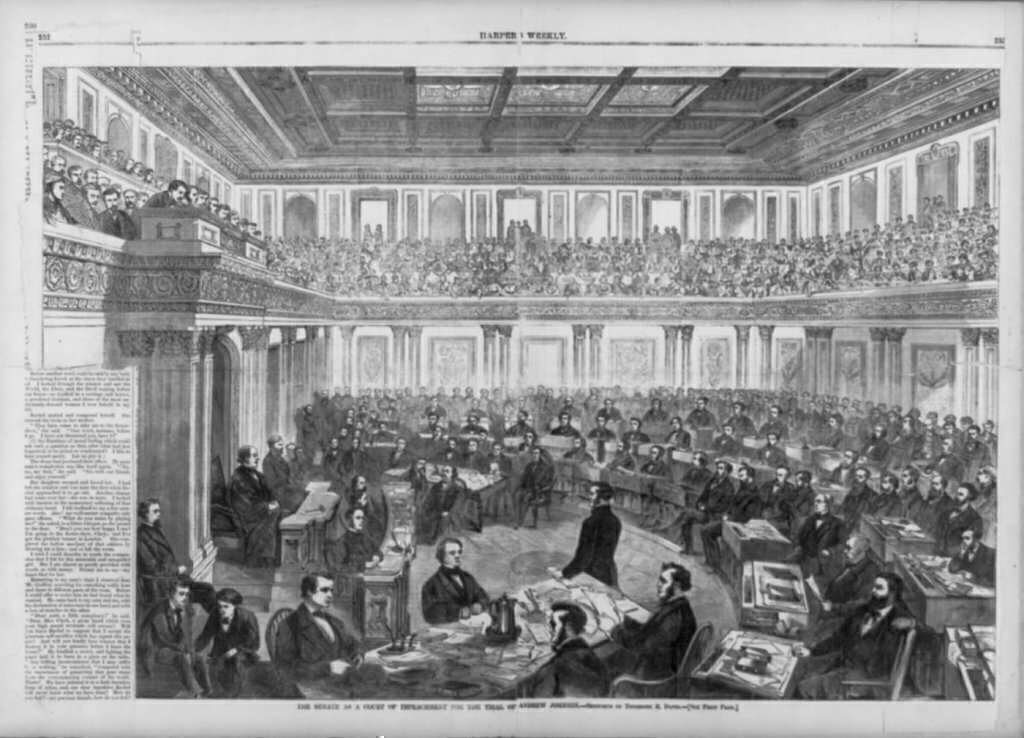

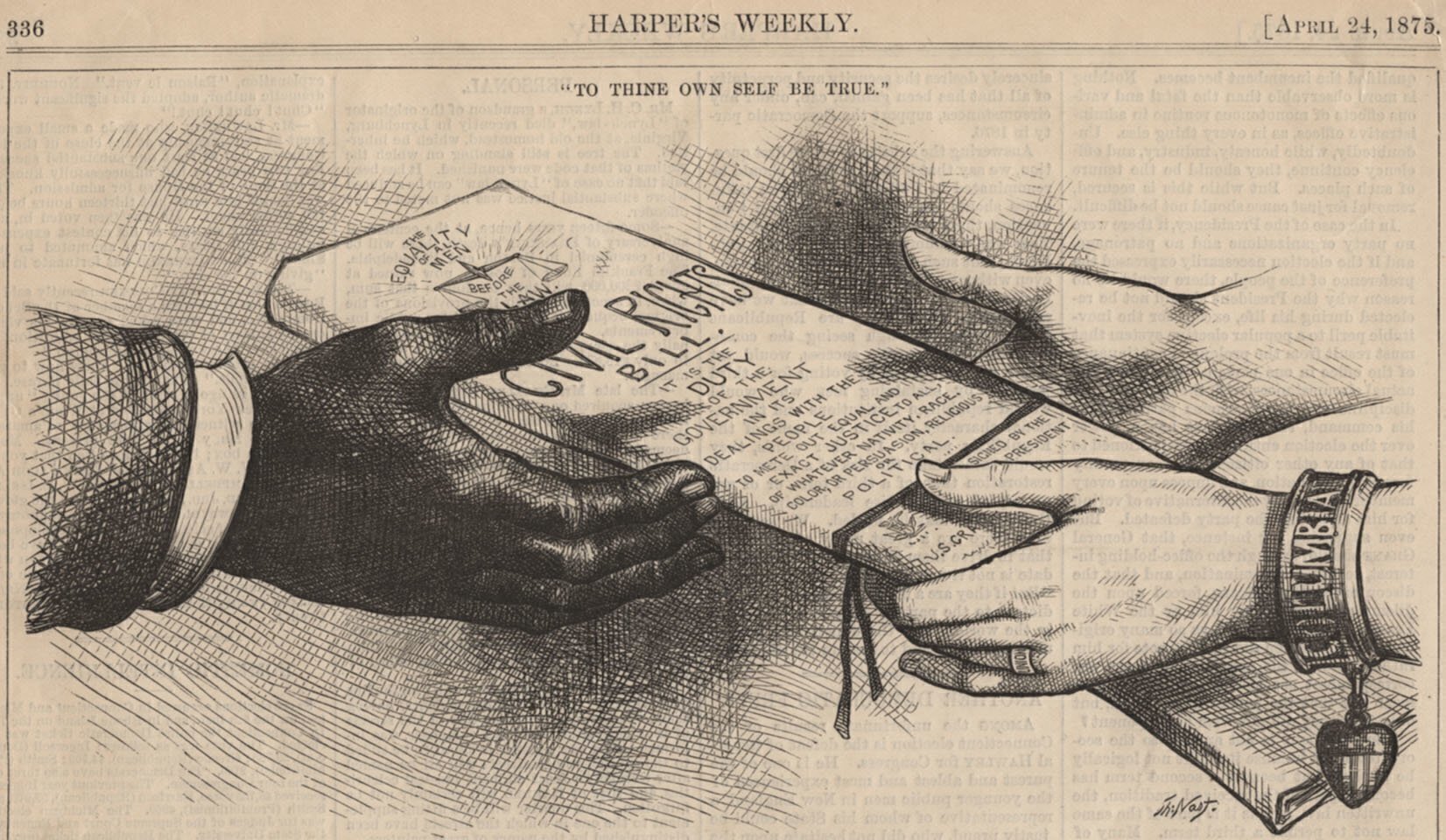

Paralleling language in the 13th Amendment, Section Five granted Congress new power to enforce its protections and pass civil rights legislation. Skeptical of the Supreme Court after the Dred Scott decision (1857), Reconstruction Republicans wanted to grant Congress these powers to protect the civil rights of all Americans, particularly African Americans in the South.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.

.jpg)