In an elegant act of “judicial jujitsu,” the Supreme Court issued its decision in Marbury v. Madison on February 24, 1803, establishing the high court’s power of judicial review.

The dramatic tale begins with the presidential election of 1800, in which President John Adams, a Federalist, lost reelection to Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Congress also changed hands, with the Democratic-Republicans achieving majorities in both chambers.

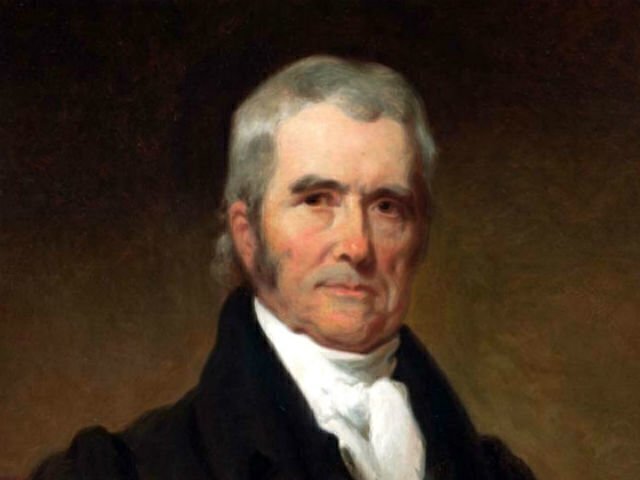

Adams could see the writing on the wall: his party had been relegated to the judicial branch. In a bid to strengthen Federalist power, he appointed Secretary of State John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the United States. Adams also worked with the outgoing Congress to create a slew of new judicial offices, which he promptly filled with Federalist jurists using the Judiciary Act of 1801.

On March 1, 1801, three days before Jefferson’s inauguration, Adams stayed up late into the night signing commissions for the new judges. The “midnight appointments,” as they came to be known, were also notarized by Marshall, still performing his secretarial duties.

But the rush of presidential transition led to the administration’s failure to deliver several of those commissions, including that owed to William Marbury, who had been named a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia.

On March 4, having assumed the presidency, Jefferson ordered Secretary of State James Madison not to deliver the commissions. Marbury sued, demanding that the Supreme Court force Madison to comply.

In Marbury v. Madison, the Court was asked to answer three questions. Did Marbury have a right to his commission? If he had such a right, and the right was violated, did the law provide a remedy? And if the law provided a remedy, was the proper remedy a direct order from the Supreme Court?

Writing for the Court, Marshall answered the first two questions resoundingly in the affirmative. Marbury’s commission had been signed by the President and sealed by the Secretary of State, he noted, establishing an appointment that could not be revoked by a new executive. Failure to deliver the commission thus violated Marbury’s legal right to the office.

Marshall also ruled that Marbury was indeed entitled to a legal remedy for his injury. Citing the great William Blackstone’s Commentaries, the Chief Justice declared “a general and indisputable rule” that, where a legal right is established, a legal remedy exists for a violation of that right.

It was in the third part of the opinion that Marshall performed the “judicial jujitsu” observed by National Constitution Center president and CEO Jeffrey Rosen in The Supreme Court: The Personalities and Rivalries That Defined America.

On the one hand, Marshall was strongly disliked by Jefferson, Madison, and the newly empowered Democratic-Republican Party. If he ordered delivery of the commissions, he risked simply being ignored by his rivals, thereby weakening the young Court. But on the other hand, siding with Madison could be seen as caving to political pressure—an equally damaging outcome.

The ultimate resolution was a deft balancing of these interests: Marshall ruled that the Supreme Court could not order delivery of the commissions because the law establishing such a power was unconstitutional.

That law, the Judiciary Act of 1789, said the Court had “original jurisdiction” in a case like Marbury—in other words, Marbury was able to bring his lawsuit directly to the Supreme Court instead of first going through lower courts.

Citing Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, Marshall pointed out that the Supreme Court was given original jurisdiction only in cases “affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls” or in cases “in which a State shall be Party.” Had the Founders intended to empower Congress to assign original jurisdiction, Marshall reasoned, they would not have enumerated those types of cases. Congress, then, was exerting power it did not have.

For his concluding masterstroke, Marshall turned to Article VI, noting that the Constitution is “the supreme Law of the Land” and that all “judicial Officers” of the United States are bound by it. Thus, a law found to be in disagreement with the Constitution—for example, the Judiciary Act—cannot stand.

To be sure, Marshall did not invent judicial review—several state courts had already exercised judicial review, and delegates to the Constitutional Convention and ratifying debates spoke explicitly about such power being given to the federal courts.

Still, the legendary Chief Justice applied it firmly and artfully to the nation’s highest court. “It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department,” he wrote, “to say what the law is.”

In the short run, Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans got what they wanted: Marbury and the other “midnight appointments” were denied commissions.

But in the long run, Marshall got what he wanted: a Supreme Court with teeth.

Nicandro Iannacci is a former web strategist at the National Constitution Center.