Note: Landmark Cases, C-SPAN’s new series on historic Supreme Court decisions—produced in cooperation with the National Constitution Center—continues on Monday, Nov 23 at 9 p.m. ET. This week’s show features the Brown desegregation decision.

The decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka on May 17, 1954 is perhaps the most famous of all Supreme Court cases. It overturned the equally far-reaching decision of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

In the Plessy case, the court decided by a 7-1 margin that “separate but equal” public facilities could be provided to different racial groups.

In his majority opinion, Justice Henry Billings Brown pointed to schools as an example of the legality of segregation.

“The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children, which has been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by courts of States where the political rights of the colored race have been longest and most earnestly enforced,” he said.

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, wrote, “In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case (referencing the controversial 1857 decision about slavery).”

“Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens,” he added.

The Plessy decision institutionalized Jim Crow laws that allowed racial segregation to continue for decades.

By 1951, the issue was heading back to the court for review, and the outlook didn’t look promising for the forces that had united to overturn the Plessy decision. The NAACP and their attorney, Thurgood Marshall, had been in court for years and had won some isolated victories.

The Brown case was actually a combination of five cases involving segregation at public schools in Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia.

The justices who first heard the case in 1953 were divided. Chief Justice Fred Vinson, from Kentucky, wasn’t convinced that Plessy should be overturned on constitutional grounds. Several other justices were undecided and possibly leaning toward upholding Plessy. Four justices seemed to be committed to overturning Plessy, but five votes were needed, and there were concerns about a divided court.

Another concern was about how the Brown decision, if it overturned segregation, could be enforced in 19 states and the District of Columbia without widespread violence.

The court decided in June 1953 to hear more arguments in the case later in the year. But in September 1953, Chief Justice Vinson died suddenly from a heart attack. President Dwight Eisenhower had promised the next Supreme Court opening to the politically powerful Earl Warren from California.

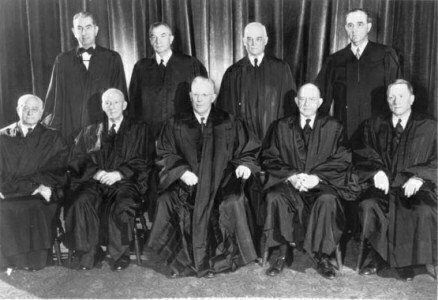

Warren was appointed chief justice and the court met in a private session in December to discuss the Brown case. Two justices took notes of the meeting, which indicate that Warren made a powerful opening statement that made it clear the court was heading toward the end of segregation.

Warren talked about the abilities of Marshall and the legal team from the NAACP.

“If oral argument proved anything, the arguments of Negro counsel proved that they are not inferior. I don't see how we can continue in this day and age to set one group apart from the rest and say that they are not entitled to exactly the same treatment as all others,” Warren said.

“At present, my instincts and tentative feelings would lead me to say that in these cases we should abolish, in a tolerant way, the practice of segregation in public schools,” he said.

Warren also made it clear he would work with the justices to find “unanimity and uniformity, even if we have some differences.”

Two justices—Robert Jackson and Stanley Reed—had concerns about the Supreme Court making a decision that would be better left to Congress. There were also questions about Marshall’s arguments, which referred much to the sociological evidence about the damage caused by segregation (and not as much to prior case law).

On May 17, 1954, Warren read the final decision: The Supreme Court was unanimous in its decision that segregation must end. In its next session, it would tackle the issue of how that would happen.

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” Warren said.

The announcement made international headlines and more than a few newspapers saw the decision as vindication for Justice Harlan’s dissent in the 1896 Plessy case.

Not long after the Brown decision, in October 1954, Justice Robert Jackson died and President Eisenhower picked his replacement from the Second Circuit Court: Judge John Marshall Harlan, the grandson and namesake of the famous dissenter.