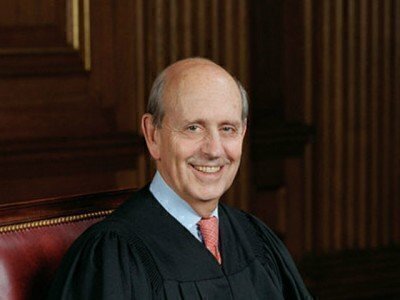

Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent in a recent death penalty case, which argued for an end to capital punishment.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“[Justice Anthony] Kennedy’s road map for considering the evolution of contemporary social norms coupled with [Justice Stephen] Breyer’s invitation to challenge the death penalty in its entirety, plausibly heralds the twilight of the death penalty in America.”

– Excerpt from a commentary by Robert J. Smith, a law professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, on July 1 on the website Slate.com.

“For the reasons I have set forth in this opinion, I believe it highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment.”

– Concluding sentence of a 41-page opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, on June 29 as the Supreme Court upheld by a 5-4 vote the lethal drug protocol used by Oklahoma in carrying out death sentences. The case was Glossip v. Gross.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

It is a truism that, throughout the existence of the United States, the death penalty has always been controversial, as a moral question and as a constitutional issue. But, excerpt for a four-year period in the 1970s, the Supreme Court has not forbidden the use of that ultimate sentence. When a moratorium that the court had imposed was lifted in 1976, capital punishment resumed, and the controversy was renewed.

From time to time since then, one or more members of the Supreme Court has argued that the penalty should be outlawed, as a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” But there never has been a majority willing to do that.

The Justices, though, have had a central role in making the death penalty a rarity in America. They have issued decisions that totally barred its use for any crime other than murder (and, perhaps, treason), and they have steadily lengthened a list of individuals who cannot be executed: persons who are insane, persons who are intellectually disabled, and youths under age 18.

Moreover, based on the premise that “death is different,” because of its finality, the court has surrounded its imposition by juries and judges with a complex, interwoven tapestry of procedural restrictions that have contributed to long delays between a death penalty verdict and an actual execution.

Justice after Justice, with various points of view, has expressed frustration with what the late Justice Harry Blackmun disparagingly called “the machinery of death.” The common complaint is that the system just doesn’t seem to work, in practice, in anything like a predictable or rational manner. It has become, largely, a hit-or-miss process, and no one is really confident that they know when a sentence is likely to be imposed, and be valid. The system, in the words of the late Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., has been “freakish.”

Still, it is always a startling development when another member of the Court, coming to the point of frustration, declares an unwillingness to go on tinkering with the system. The latest was Justice Stephen Breyer, who last month announced that he would no longer “try to patch up the death penalty’s legal wounds one at a time,” and proceeded to produce a lengthy, point-by-point argument for casting it aside under the Eighth Amendment.

But it is also noteworthy that his effort drew the specific support of only one other Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. And it would take the votes of at least two more Justices – that is, a minimum of four – to even grant review of the constitutionality of death sentencing.

It is not even a certainty, of course, that the other members of the court’s more liberal bloc – Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor – are prepared to join in forcing the issue. But, assuming that they were, would four Justices commit the court to reviewing the Eighth Amendment question without some assurance that a fifth vote would be available to make a full majority in the end?

Of the other members of the court, of course, one could immediately rule out Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, who each wrote a strongly worded opinion seeking to answer Justice Breyer’s critique. It seems unlikely that Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., and Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., would differ much from Scalia and Thomas on the point.

That would leave, as high-level controversy is often left within this court, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy. It is true that Kennedy has taken the lead in decisions that withdrew death penalty eligibility for younger teenagers and mentally disturbed persons.

But Kennedy has seldom dissented when the court has allowed executions to proceed, when eleventh-hour appeals are made by death-row inmates. He has not been willing, for example, to help make a majority to give death-row inmates a right even to test the workability of execution protocols. And, of course, he provided a crucial fifth vote when the court last month upheld one of the more controversial of those protocols, for lethal-drug executions.

It has been suggested (as, for example, in the comment quoted above by a North Carolina law professor) that Justice Kennedy could become a fifth vote to strike down death sentences, because of his strong belief in the idea that constitutional norms do change as the times change, and that each generation is charged with deciding for itself how to define basic constitutional freedoms in a new era.

That is a bold idea, but Justice Kennedy is also known to have a distinctly cautious streak about how far he is willing to go to have the court create new constitutional rights, unless he senses that a new right is absolutely essential to his concept of liberty and human dignity.

He, perhaps more than any other single Justice, would be sorely challenged to decide the question of whether the death sentence must now be forbidden. He has given no sign, over the years, that he is prepared to give up on the idea that, little by little, the system can be made fairer and constitutionally respectable.

In short, if the ultimate Eighth Amendment issue were now to be raised directly before the court, Kennedy’s vote to end capital punishment, once and for all, would be very doubtful, and certainly not predictable.