Constitution Daily contributor Lyle Denniston, who has written about the Supreme Court since 1958, looks at the current contentious nomination process in the context of the Court's long-term institutional strength.

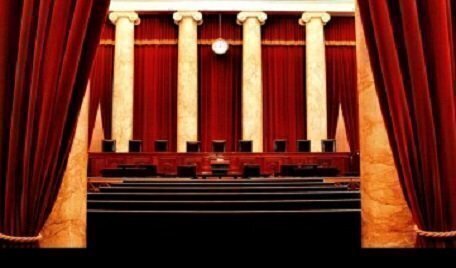

The United States Supreme Court is a hardy institution. It has been at work for 228 years, and only last week it was issuing new orders, following an old routine of picking out new cases to decide. People visiting the building or working there probably noticed no difference in the norm.

The United States Supreme Court is a hardy institution. It has been at work for 228 years, and only last week it was issuing new orders, following an old routine of picking out new cases to decide. People visiting the building or working there probably noticed no difference in the norm.

The eight Justices at work almost certainly were aware, however, of what was happening just a short distance away on Capitol Hill. There, in a Senate office building, the scene was one of tumult, blistering anger, and parliamentary chaos. The now-predictable political mess of reviewing a new nominee to the Court was getting even messier.

As the nominee, Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh, grew increasingly agitated and the senators increasingly insulted each other, some observers around the nation began to ask themselves some hard questions: Can the Judge, if approved, ever outlive this and become an impartial Justice? Will the Supreme Court be permanently damaged by this? Is a just America a thing of the past?

News articles began appearing, quoting the sage observations emanating from the academy, from amateur psychologists, from wise historians. Much of what they said could be summed up in simple phrases: gloom and doom, pain and misery, agony and woe.

It is surely true that today and in coming days as the Kavanaugh episode moves toward an uncertain end, Washington will become more polarized, no one is going to wind up pleased with the outcome, women will once again feel betrayed by the culture, and much of America may well feel lasting shame.

On Monday, the Supreme Court – with one empty seat on the bench – will formally open its new term and start hearing new cases. It is totally predictable that not one word will be said in that chamber about Judge Kavanaugh and about the furor over his nomination or about the impact of all of that on the Court itself.

Instead, everyone directly involved will start by focusing on a case named Weyerhauser Co. v. Fish and Wildlife Service. No matter how that case ultimately gets decided, the earth will not be shaken; it would not be on the scale of, say, Brown v. Board of Education.

The case is about the federal government’s power to prevent tree-cutting on 1,500 acres of land that could be home to an endangered species, the dusky gopher frog. The two sides vigorously dispute whether that species may ever be able to live in the protected area.

The case, of course, involves important principles of environmental and property law and both sides in the case cared enough to energetically dispute it before that final tribunal.

Among the lessons to be read into this are these: The Court is a court, it decides legal issues that range from narrow to profound, it must view the case as it exists in the filed record, and all of the Justices must work together as a group to decide who wins.

Not all of the work that would confront Kavanaugh if he were to become a Justice would be a test of what he is feeling about American politics, about issues that test his conservative judicial philosophy, about how he reacts to legal briefs filed by groups that opposed or favored his nomination, about his view of women, or about his potentially abiding resentment of members of the Democratic Party.

But there definitely will be times, and they could be crucial times in the history of the law when he would directly confront issues potentially capable of arousing the temper that he so clearly displayed last week in the Judiciary Committee’s witness chair. No Justice is an automaton doing judicial work mechanically and without any feelings; none is anything less than the sum of the parts of a personal past.

Ninety-seven years ago, a respected New York state court judge who would later become a Supreme Court Justice, Benjamin N. Cardozo, gave the Storrs Lectures at Yale Law School. The lectures were soon published in a book now widely regarded as a classic: “The Nature of the Judicial Process.”

Here was a sample of Cardozo’s wisdom:

“There is in each of us a stream of tendency, whether you choose to call it philosophy or not, which gives coherence and direction to thought and action. Judges cannot escape that current any more than other mortals. All their lives, forces which they do not recognize and cannot name, have been tugging at them – inherited instincts, traditional beliefs, acquired convictions; and the resultant is an outlook on life, a conception of social needs, a sense in [William] James’s phrase of ‘the total push and pressure of the cosmos’…We may try to see things as objectively as we please. None the less, we can never see them with any eyes except our own.”

Brett Kavanaugh, for 12 years as a federal appeals court judge, has been seeing legal matters through his own eyes. The vision that has guided him is thoroughly conservative, strongly devoted to greater power in the presidency and regularly skeptical of reading constitutional guarantees of civil rights expansively, routinely averse to seeing things in the Constitution that are not explicitly stated there in the actual words.

He no doubt would see things in much the same way if he were a Justice and those visions were tested in actual cases. In short, he would be one of the Court’s most conservative Justices, probably closer in his judicial philosophy to Justice Clarence Thomas than to any other current member. Kavanaugh would be exactly what the Federalist Society wanted in recommending him to President Trump.

If Benjamin Cardozo was right back in 1921, and he doubtless was, those tendencies would accompany him to the Court.

But would Kavanaugh take with him, and be a captive of, the anger and hurt feelings of the past few weeks? Would he, in short, have a judicial temperament? He might not, but would that make a difference; would that damage the Court?

The answer probably could lie in the disciplines of the Court’s methods and habits, in the almost constant need to persuade others who bring their own visions and are just as smart as he is, in the reality that what he personally writes and makes public ought to read like law rather than spite, and that his ultimate standing in history will depend at least in part upon whether he has overcome the emotion of his experience as a nominee. His colleagues would help him with that.

But for the Court itself as an institution, it would remain true that he is but one of nine, and equally true that its history shows it can survive others among its members who have been appropriately forgotten.

Its survival also depends – as it always has, throughout history -- on other institutions in government or in the private world that can deal adequately with perceived social or cultural harms done by the Court, even to the point of amending the Constitution if that is what it takes.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.