It was on this day in 1790 that the United States Supreme Court opened for business. The court back then bared little resemblance to the current one, but it certainly had some interesting characters.

The original six Justices were appointed by President George Washington and confirmed by the Senate. The group included a Chief Justice who became the most-hated man in America for a time; a justice who didn’t want to the serve despite the Senate’s confirmation; and another justice who literally jumped into Charleston Bay when he lost his seat on the bench.

The original six Justices were appointed by President George Washington and confirmed by the Senate. The group included a Chief Justice who became the most-hated man in America for a time; a justice who didn’t want to the serve despite the Senate’s confirmation; and another justice who literally jumped into Charleston Bay when he lost his seat on the bench.

The first business of the First Congress was to establish a law setting up the Supreme Court. The framers had made provisions for the court in Article III, Section 1, of the Constitution, but it took the Judiciary Act of 1789 to make the court a reality.

Lawmakers passed the Judiciary Act on September 24, 1789, which established the framework for the Supreme Court, as well as circuit and district courts and the attorney general’s office. President George Washington named six Supreme Court justices who were approved within two days by Congress.

The date of February 1, 1790 was set for the Court’s first meeting. John Jay, who Washington’s choice for Chief Justice, had to wait a day to start a full session after travel issues delayed some of the jurists.

The first meetings included four of the six original justices: John Rutledge was in New York but decided not to attend the session, while Robert Harrison was too ill to travel to the session, and he had indicated he would resign from the Court. (President Washington confirmed Harrison’s resignation about a week later.).

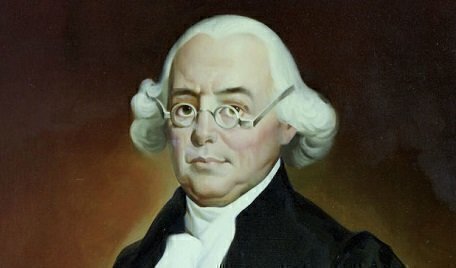

In addition to Jay, James Wilson, William Cushing, and John Blair Jr. were in attendance. Each had interesting stories and backgrounds but had little to do at the Court’s first two sessions in February and August 1790. Jay and Wilson were also significant figures in the Revolution and the making of the Constitution.

The Judiciary Act has created the “inferior” courts that had just started their operations, so there were no appeals to be heard by the Supreme Court. The justices spent their time approving bar appointments and organizing the court system. The Supreme Court didn’t get its first case for a year, and it took two years for the first argument to be heard by the justices in Philadelphia, where the federal government had relocated.

The Supreme Court justices were also required to “ride circuit,” and hold hearings twice a year in one of three judicial districts. Circuit duties weren’t popular with the first justices and they took up most of their time. Not until 1794 did the Court meet in extended sessions.

Here is a brief look at each of the six original Supreme Court justices.

John Jay. The first Chief Justice had five of The Federalist essays, but his role as the first Chief Justice included two campaigns for governor in New York (while he was still a justice) and his negotiation of the controversial Jay Treaty with Great Britain. The treaty Jay negotiated, while he was still on the Supreme Court, was unpopular. (The chief justice later said he could find his way across the country by the light of his burning effigies.) Jay left the court in 1795 after finally winning a gubernatorial election.

James Wilson. Wilson was a key figure at the Constitutional Convention who had a troubled career after joining the high court. Wilson was a leading legal theorist, but he was also troubled by bad debts after getting involved in some land deals. Wilson was imprisoned twice for bad debts while he served on the Supreme Court, and he missed several court sessions as he avoided bill collectors. Wilson died in 1798 while still on the bench. He was staying at the house of a friend in North Carolina, out of the reach of creditors, and riding the Southern District court circuit.

John Rutledge. Rutledge also was at the Constitutional Convention and an important figure in South Carolina when he was first named to the Supreme Court. He served two years on the bench and quit in 1791, without hearing a case. President Washington then asked Rutledge to return as chief justice to replace Jay in 1795 while the Senate was in recess, and Rutledge heard two cases during that time. However, the Senate rejected Rutledge’s permanent nomination after he publicly criticized the Jay Treaty with some inflammatory language (the only time that a recess appointment to the Court has been rejected). Rutledge jumped off a wharf in Charleston in a failed suicide attempt after he heard about the Senate vote (he was rescued by two slaves who saw the incident). His public career was over.

William Cushing. The longest-serving justice appointed by Washington, he remained on the court until 1810. But Cushing rejected the job of chief justice in 1796 even though Washington nominated him and the Senate had unanimously approved the nomination. (Perhaps he saw what happened to Jay and Rutledge.)

John Blair Jr. He was a highly regarded jurist from Virginia who served on the court until 1795 when he resigned. Blair came from a distinguished family and he attended the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. He said little at the convention but was strongly allied with James Madison.

Robert Hanson Harrison. Harrison was one of Washington’s aides-de-camp during the Revolutionary War and later became his military secretary. After serving as the chief justice for Maryland’s court system, Washington nominated Harrison to the Supreme Court. Sickness kept Harrison from accepting the position and he died in April 1790.