Every four years, 538 people meet in 51 locations around the United States to pick the winner of the presidential election. So who are the members of the Electoral College?

Political parties within states pick people to serve as electors, under rules approved by state legislatures. The electors are usually party leaders or members.

Here are the basics: The Constitution’s Article II, Section 1 spells out the basic Electoral College rules. A majority of electors is needed to elect a President; members of Congress or people holding a United States office can’t be electors; electors can’t pick two presidential candidates from their own state, and Congress determines when the electors meet within their states (or in the federal district). The total number of Electoral College members equals the number of people in Congress and three additional electors from the District of Columbia.

The list of the electors, or the slate of electors, within a state usually doesn’t appear on the election ballot. States have different rules for when official slates are submitted to election officials. Each political party decides how to submit its slate of electors, at the request of its presidential candidate. The state decides when that slate needs to be submitted.

On Election Day, people vote for a Presidential and Vice Presidential candidate and the slate of electors that represents those candidates. The electors of each state convene after the election, under current federal law, on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December. (Any disputes within the states over electors must be resolved by December 13.)

They almost always meet in person at the state capital. This year, they will meet on December 19, 2016. In 48 of 50 states, just the electors who represent the candidate with the most popular votes on Election Day each get to cast votes in the Electoral College election. (Maine and Nebraska split votes by congressional district.)

Each state group sends its endorsed, official vote count certificate to the Vice President (acting as President of the Senate), state officials, the federal court that had jurisdiction over the state capital area, and the federal Archivist. The vote certificates must be received in Washington by December 28.

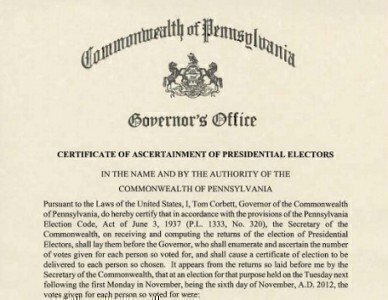

For example, back in 2012, President Barack Obama won the popular vote in Pennsylvania and its 20 electoral votes. On December 10, 2012, the governor and secretary of state for Pennsylvania filed a certificate of ascertainment, listing the election vote count, and the names of all electors for all eligible parties. The Pennsylvania electors for the winning party met and signed a Certificate of Vote on December 17, 2012 at the state capital in Harrisburg, Pa. Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, a Democrat, was among the 20 electors.

In 2017, the new federal Congress convenes on January 6 for the official Electoral College vote count. The Vice President will open the vote certificates and pass them to four members of Congress, who count the votes. If there is a majority winner with at least 270 electoral votes and there are no objections filed by members of Congress, the Presidential election is certified and over. If there isn’t a majority winner, the election is sent to Congress to decide. The House decides who is President; the Senate decides who is Vice President.

So what happens if an elector doesn’t vote for the candidate he or she was pledged to represent? States have the power to punish faithless electors with fines and possible jail time, but once certified votes are sent to Washington, it’s up to Congress to accept that vote.

There have been more than 150 faithless electors in Electoral College history for various reasons. In some cases, Vice Presidential candidates died between Election Day and the Electoral College voting date. In other cases, electors switched votes for various reasons.

In one case, back in 1968, Congress used its powers under federal law to decide the fate of a faithless electoral voter who voted for George Wallace instead of Richard Nixon. After objections were filed in the House and Senate, both voted separately to accept the vote. In those special sessions, the House and Senate met separately for no more than two hours. And both the House and Senate must agree to an objection, and then that vote isn’t counted.

In 2004, the House and Senate agreed to consider a dispute over Ohio’s certificate, and both groups approved the submitted certificate in separate votes.