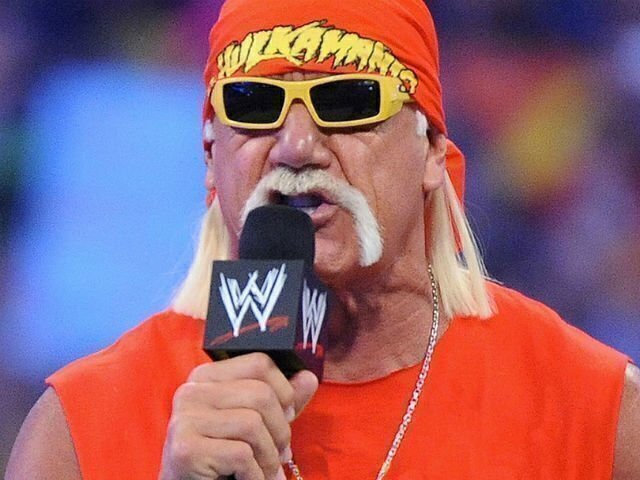

The interests of tabloid journalists and legal bloggers converged this week, when a jury in Florida state court determined that the gossip site Gawker owed former WWE star Hulk Hogan over $100 million in civil liability damages.

In 2012, the site posted a hidden-camera sex tape of Hogan, whose given name is Terry Bollea, without his permission and without approaching him for comment before publication. At the core of the intense, protracted legal battle that followed Gawker’s publication of the video is a conflict between Gawker’s First Amendment claim of press freedom, and Hogan’s assertion that his right to privacy had been violated.

After the video was initially posted on Gawker, it quickly racked up over four million page views, and Hogan petitioned a federal district court in Florida to compel Gawker to take down the video after the website refused his requests to do so. Gawker stood by its post and asserted that Hogan’s legal claim was without merit, as the publication of the video was protected by the First Amendment’s guarantee of press freedom. Gawker writers explained that “the Constitution does unambiguously accord us the right to public true things about public figures,” while Hogan maintained that, even though he was a public figure, publication of this sort of intimate and private material crosses the line.

The question of whether to allow Gawker to keep the video posted turned on the court’s assessment of whether the video amounted to “newsworthy” material. Previous First Amendment cases dictate that whether information is “newsworthy” can depend on the social value of the published material, whether the information is about a person who voluntarily put himself in the public eye, and the extent to which the material reported was a private matter.

The district court interpreted the First Amendment as demanding deference to Gawker, as “the judgment of what is newsworthy is primarily a function of the publisher, not the courts.” The court went on to underscore how multiple previous Supreme Court decisions embraced the principle that “even minimal interference with First Amendment freedom of the press causes an irreparable injury.”

In rejecting Hogan’s appeal, the district court maintained a broad definition of newsworthiness, followed a tradition of deference to journalists, and embodied the general trepidation of courts to judge whether speech should be protected based on an assessment of its content.

After this initial defeat, Hogan sought an injunction against Gawker in Florida state court, which ordered that the video be taken down. He also sued Gawker in Florida state court for civil damages in order to compensate him for the “massive, highly-intrusive, and long-lasting invasion of privacy.”

The trial again would turn on whether Gawker’s lawyers could convince the six jury members that the video was “newsworthy” material and fell under a class of speech protected by the First Amendment. The jury ultimately determined that the video failed to meet this standard, and while Gawker plans to appeal, they are currently facing a $115 million judgment.

Decisions in other state courts and federal circuits help put this case into context. In 1942, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that Time Magazine violated the privacy of Dorothy Barber when it published a photo of her along with a story about her unique medical condition. The photo, which was taken against her will, did not contribute to the public interest of the news story and was an unnecessary violation of her privacy.

While privacy standards are different for celebrities and individuals who chose to open themselves to public scrutiny, other courts have still recognized their privacy claims. Dealing with a case somewhat analogous to that of Hulk Hogan, a district court in California determined in 1998 that musician Bret Michael’s privacy was violated when a sex tape was circulated without his permission. “The privilege to report newsworthy information is not without limit,” the court determined, and “the private facts depicted on the Michaels tape had not become public” by virtue of Michael’s celebrity status.

The court in the Michael’s case looked to a 1975 decision in the California circuit that determined that claims of public interest fail when material in question is a “morbid and sensational prying into private lives for its own sake, with which a reasonable member of the public, with decent standards, would say that he had no concern.”

Still, Gawker’s lawyers maintain that Hogan had made salacious details about his life a matter of public interest after he talked openly about such matters in other forums. Critics have already expressed their concern with the Florida court’s judgment, and see it as a dangerous beginning that could open up media outlets to a slew of civil liabilities claims.

While the details of this particular case may border on the absurd, critics assert that, unless the right to determine what is newsworthy is reserved exclusively to media outlets and readers, a dangerous chilling effect could stifle the press.

Jonathan Stahl is an intern at the National Constitution Center. He is also a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in politics, philosophy and economics.