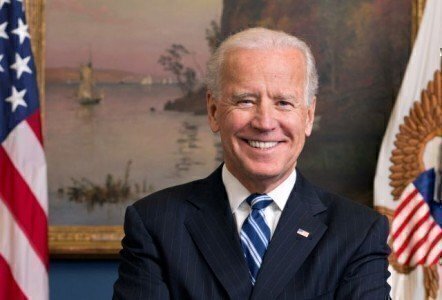

The New York Times reported last week that Vice President Joe Biden briefly considered resigning after his son’s death. But the serious implications of such a move would be well understood by Biden, who is familiar with Congress and the executive branch.

The exact quote in the Times was, “in a sign of the conflicting pressures surrounding Mr. Biden, the vice president has told people that the terminal brain cancer of Beau Biden, who died in May, had caused him to consider resigning the vice presidency to take care of his grieving family, though those aware of the vice president’s thinking say that idea never became too serious.”

To paraphrase Biden, any vice presidential resignation would be a big deal. It has only happened twice since 1789. In recent years, the Vice President’s constitutional role has been enhanced by the 25th Amendment. The amendment made the Vice President a key figure in any crisis that involves a presidential “disability.” It also established a process where Congress must approve a replacement Vice President. In the current case, there is a Democrat as President with the Republicans controlling the House and Senate. Could all the parties agree on a replacement Vice President in the current politically charged climate in Washington?

The answer is probably "Yes." The reality is that despite political divisions, a President and Congress would probably move quickly to fill a Vice Presidential vacancy because of the considerable problems triggered by the lack of a Vice President.

In October 1973, President Richard Nixon nominated Gerald Ford to replace Spiro Agnew just two days after Agnew’s resignation as Vice President. Ford was confirmed within two months in a very difficult political environment, with Nixon (a Republican) getting a Congress controlled by Democrats to approve Ford. A year later, Ford was able to get Nelson Rockefeller confirmed as his replacement after a four-month process.

A Vice Presidential resignation raises serious constitutional questions. While on the surface, the Vice Presidential “job description” seems light in the Constitution, compared with the expectations for the President, the 25th Amendment established some critical roles for the Vice President in cases where the President was unable to serve temporarily or permanently.

The 25th Amendment was ratified by the states in 1967 and it cleared up a lot of issues about presidential succession that were unresolved (or unanticipated) by the Founding Fathers. The Founders established the office of Vice President as a late addition in the constitutional drafting process. On September 7, 1787, the delegates approved the office after a very brief debate, which focused more on the Vice President’s ability to cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate.

It was up to Vice President John Tyler, who found himself in an awkward position after President William Henry Harrison’s death in 1841, to set the precedent for presidential succession that lasted until 1967. In Article II, Section 1, the Constitution said that, “In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President.”

After Harrison’s death, there was confusion about Tyler’s status as Acting President or as the actual President, in title as well as function. Tyler boldly declared himself as President for the remainder of Harrison’s term and Congress recognized his title. The precedent held after the deaths of six Presidents in office – Taylor, Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, Harding and Franklin Roosevelt. But after President Dwight Eisenhower had health problems, a congressional effort started to clear up presidential succession questions. President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 made the process imperative.

The 25th Amendment made it clear that the Vice President becomes President in the case of death, resignation and removal from office. It also said that a President can nominate someone to become Vice President if that office is vacant, with the approval of Congress.

However, Section 3 and 4 established new roles for the Vice President if the President were unable to perform his or her official duties. Section 3 allows for a President to communicate a disability to Congress and it has been done several times when Presidents have undergone routine medical procedures. Under Section 3, the Vice President temporarily acts as President.

Section 4 deals with a different scenario – when a President is unable or unwilling to communicate a disability. According to a Congressional Research Service analysis by Thomas Neale, Section 4’s wording makes it clear that “the Vice President is the indispensable actor in section 4: it cannot be invoked without his agreement.”

Under Section 4, the Vice President, either acting with the Cabinet or a group designated by Congress, can declare the President disabled. If the President is able to disagree with that decision, the Vice President then can start a procedure where two-thirds of the House and Senate must agree that the President can’t perform his or her duties, and the Vice President remains as Acting President.

“It can be further suggested that Section 4, like the impeachment process, is so powerful, and so fraught with constitutional and political implications, that it would never be used, except in the most compelling circumstances, since its invocation might well precipitate, ipso facto, a constitutional crisis,” Neale noted.

Certainly, one potential constitutional crisis would be the lack of a Vice President in office to start a Section 4 disability review of a President. Another is the lack of a constitutional or legal precedent for someone to act as a temporary Vice President, to start the Section 4 review process.

And the current federal code, which incorporates the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, allows for the Speaker of the House to act as President if “there is neither a President nor Vice President to discharge the powers and duties of the office of President.” The law also says the Speaker is “Acting president in part on the inability of the President or Vice President, then he shall act only until the removal of the disability of one of such individuals.” So who would determine that a Vice President who was disabled is able to hold office again?

Clearly, the constitutional role of the Vice President has expanded since 1787, and it seems unlikely that the position would remain vacant for long in the era after the 25th amendment was ratified. But before 1967, the office of Vice President was vacant 16 times due to deaths, resignations and assumptions of the President's office.

John D. Feerick, who played an important role in drafting the 25th Amendment, discussed these scenarios in depth in a 2011 Fordham Law Review article.

“In situations where the Vice Presidency is vacant (or the Vice President is disabled) and the President is disabled but has not declared himself to be under Section 3, what happens is not entirely clear,” Feerick said. He points to scholarly opinions that the person next in line under the Presidential Succession Act would need to make disability determinations in there is no Vice President.

“Therefore, the Speaker of the House would be the person to make the disability determination in the event no Vice President could do so. However, there is no current law in place to provide procedures and safeguards to ensure that the Speaker (or next in line) does not abuse this power (such as the Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s requirement that the Vice President has supporting opinion from a majority of the Cabinet). I believe a good case can be made that Congress has the power to create such a law,” Feerick argues.