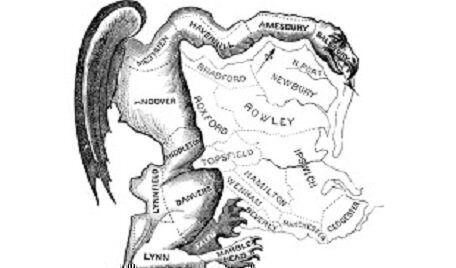

As the dust settles on the 2018 midterm elections, one outcome that could last longer than the immediate vote is the election’s impact on partisan gerrymandering – the practice of lawmakers drawing districts to favor a party in power.

In April 2021, states will start redrawing election districts based on the 2020 federal census. There have been constant legal challenges to the practice when it has been used by Democrats and Republicans alike to “stack” districts to favor candidates in federal and statewide elections. But much of the fight over partisan gerrymandering will take place before 2021.

In April 2021, states will start redrawing election districts based on the 2020 federal census. There have been constant legal challenges to the practice when it has been used by Democrats and Republicans alike to “stack” districts to favor candidates in federal and statewide elections. But much of the fight over partisan gerrymandering will take place before 2021.

For example, on Wednesday, a federal court told Maryland officials to redraw its election map because it favored the Democrats. That case had been returned by the United States Supreme Court to the federal court for review.

On Tuesday night, voters in Michigan and Colorado approved anti-gerrymandering measures that will put independent commissions, and not elected officials or elected judges, in charge of drawing congressional and state districts. Utah could approve a similar measure when Tuesday night’s final results are tabulated. Missouri voters also approved an independent demographer to configure maps bound to a statistical fairness model.

These states join six other states that have independent commissions or measures to draw election districts. Earlier this year, Ohio voters approved measures to guarantee both parties have a strong say in the mapping process.

Perhaps the biggest development on the partisan gerrymandering front was in Pennsylvania, where maps instituted by the state’s Supreme Court might have factored in a swing of four House seats to the Democrats. The state court had ruled in January that state legislators devised extreme gerrymandered maps back in 2011 after the last census. Current lawmakers who supported those maps accused the state Supreme Court’s elected Democratic majority of using its own gerrymander to redraw the state map.

The United States Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal in the Pennsylvania case, and the Pennsylvania courts said the 2011 map violated the state constitution’s promise of “free and equal” elections. The successful challenge of gerrymandering within the context of a state constitution could lead to similar challenges in other states, most likely putting those decisions outside of the United States Supreme Court’s consideration.

Another outcome from the 2018 midterm election is the election of governors, where the Democrats gained seven seats. Governors play a role in the restricting process as political leaders and the holders of veto powers over legislation. And many officials at a state level in the 2018 election won’t be up for re-election in 2020, putting them in position to determine and vote for election maps in 2011.

Of course, the Supreme Court could have something to say in several gerrymandering lawsuits it has returned to the state for review. But so far, the Court has been reluctant to devise tests related to extreme partisan gerrymandering.

Scott Bomboy is editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.