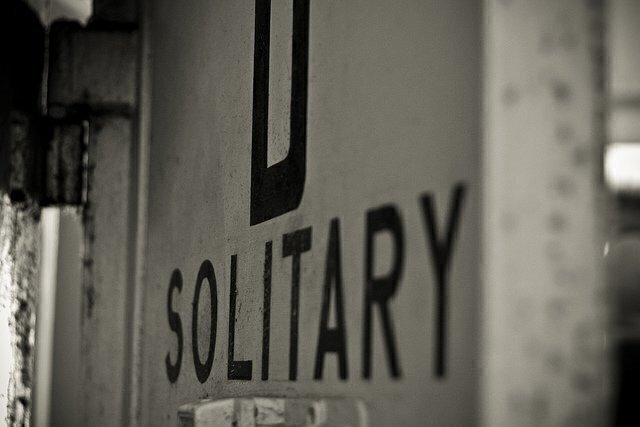

In a concurrence on a recent capital punishment case, Justice Anthony Kennedy quickly affirmed the totality of the majority opinion, and then used the remainder of his writing to criticize the practice of solitary confinement.

Freely quoting sources ranging from psychological experts to novelists Charles Dickens and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the traditionally conservative Justice deplored a harsh system of perpetual solitary confinement, in which an estimated 25,000 prisoners are held “in … windowless cell[s] no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day.” Many of these inmates are isolated “regardless of their conduct in prison.”

The practice of penal isolation had no bearing on this particular case, but it is common practice for Justices to opine on issues they wish to see brought to the Court. To some observers, Kennedy’s departure signaled an invitation for the Supreme Court to consider the constitutionality of solitary confinement.

In fact, Kennedy may have underestimated the true number of isolated prisoners, as the 25,000 number comes from a decade-old study of supermax prisons. Over 44 states have these special prisons (Urban Institute, 2006). It is difficult to determine the exact number of total inmates held in “restrictive housing,” but some estimates are higher than 80,000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2005). Texas alone holds about 9,000 prisoners in solitary confinement at any given time (Solitary Watch).

While many of these prisoners are not permanently held in isolation, a substantial portion are, and for disputable reasons. Some are simply “nuisance prisoners,” who attempt to defend themselves against legal or other abuses, and are thusly punished by authorities.

There is also a longstanding practice of keeping LGBT prisoners in near permanent solitary confinement, under the guise of protecting them from abuse.

Perhaps most prevalent is the isolation of inmates with mental health issues—the population that may suffer the most. According to the ACLU, “Solitary confinement is psychologically difficult for even relatively healthy individuals, but it is devastating for those with mental illness. … Many engage in bizarre and extreme acts of self-injury and suicide.”

Finally, the majority of death row inmates, around 3,000 inmates in 35 states, are held in perpetual confinement, often over years during the appeals process (ACLU, 2013). One such case looks like a promising vehicle for the issue to reach the Supreme Court.

Virginia is known for its tough stance on solitary confinement: all death row inmates are automatically isolated until their executions, a practice that state officials defend as necessary because condemned prisoners have less to fear from causing trouble, if given the opportunity. Indeed, the four plaintiffs at issue here have committed horrible capital crimes, including killing police officers and children, and committing rape.

Yet the practice of holding inmates alone for 23 hours a day could be considered cruel and unusual punishment, with limited public safety benefits and a devastating impact on mental health. The district judge who will hear the case appears open to this argument—the Hon. Leonie Brinkema has said that she does not understand why Virginia “is insisting on maintaining this level of these conditions. They really need to be thought about carefully.”

A different suit brought by fellow Virginia death row inmate Alfredo Prieto led Brinkema to declare automatic confinement unconstitutional under the due process guarantee of the 14th Amendment—a decision that was ultimately overturned by the Fourth Circuit. The new plaintiffs, led by Thomas Porter, are petitioning for the same relief, but they are also invoking the “cruel and unusual punishments” prohibition of the Eighth Amendment and the equal protection guarantee of the 14th Amendment.

If Brinkema rules for the plaintiffs and the government appeals, the Fourth Circuit would hear the case and likely hold the automatic use of solitary confinement to be constitutional, as it did in the Prieto case. An appeal at that level could be taken up by the Supreme Court.

With Kennedy indicating common cause with the more liberal justices, a five-Justice majority against solitary confinement could significantly reshape the criminal justice system.

Will Field is an intern at the National Constitution Center.