* Editor’s Note: The author will discuss his latest book, Worst. President. Ever., at the National Constitution Center on Monday, November 28 at 12 p.m. Learn more and reserve tickets.

* Editor’s Note: The author will discuss his latest book, Worst. President. Ever., at the National Constitution Center on Monday, November 28 at 12 p.m. Learn more and reserve tickets.

Going around the country promoting my book, Worst. President. Ever. – an irreverent biography of James Buchanan – the past several weeks, I noticed that from truck stops to university halls, bookstores to national monuments, presidential libraries to convenience stores, people just seemed exhausted by the 2016 election.

From ground level – I drove more than 4,000 miles in about five weeks and spoke either on the radio or in person at about three dozen places from Minnesota and South Dakota to Georgia and South Carolina – the overall populace seemed to me to be anxious, no matter what stripe of partisan they were.

They all seemed to want to unload those anxieties to a guy who wrote a book named Worst. President. Ever. as if I were a TV-type psychologist, not a journalist and historian, as if I had a magic-bullet answer to their presidential concerns.

To ease their minds, I would try to direct them backward to the 1856 election, the one that gave us my pick for Worst President, my friend Mr. Buchanan.

It was a curious time in American party politics. In the beginning of 1853, there was a Whig Party incumbent in office, the lame duck Millard Fillmore. Fillmore, who ascended to the presidency on the death of Zachary Taylor, had not been re-nominated by his party, which chose to go with what got them into the White House, a general (only William Henry Harrison and Taylor, two war heroes, had been elected as Whigs). Unfortunately, Winfield Scott, at 6-foot-5, the tallest man ever to run for president, got clobbered by a guy who served under him in the Mexican War, Franklin Pierce.

Within months, the Whigs were gone from the national scene. In the previous months, their two long-time hod-carriers, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, had died and there was little back bench to take their place after the slaughter of the 1852 presidential race.

Out of their ashes, two parties emerged. Many urban areas had seen an influx of German and Irish immigrants, eager to work and make it in the New World. Alarmed by this influx of Catholics “taking our jobs,” a nascent anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic movement took root. It was formally called The American Party, but most people, including most of its members, called it the Know-Nothing Party.

Even the most fervent 2016-election-worrier gets a laugh at an election where one party actually called itself the Know-Nothings, as I try to compare them to the “Hogan’s Heroes” TV character Sgt. Schultz, who always said, “I know nothing,” when asked about what was going on at his German POW camp. That was the case with these 1856 Know-Nothings, who were not supposed to reveal what happened at the party’s secret meetings.

Not so secretly, the party had a tough time finding a candidate to take them up on the top spot – until they found the most teed-off politician in the country. Millard Fillmore was hardly overjoyed at being passed over by the Whigs for the feeble candidate Scott and badly wanted back in the White Hose, so badly that even though he had hardly made any anti-immigrant or anti-Catholic statements, he was willing to buy in with the Know-Nothings.

Meanwhile, other ex-Whigs, and even a few Democrats, were tired of the South’s dependence on slavery and thought they could make a party out of those who wanted to stop its potential spread to the newer territories to the West. Wanting to co-opt a little posterity, they called themselves “Republicans,” the second part of the “Democrat-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the part dropped by the contemporary Democratic Party.

William Seward, a New York formerly-Whig U.S. Senator, seemed like the obvious choice for a candidate. But Seward looked around, saw that the new party was not going to get on many Southern-state ballots, and decided to sit this one out.

Like the Know-Nothings, the Republicans were looking for some patriotic fervor, so they both had their nominating conventions in Philadelphia, both buildings but a few blocks’ walk to Independence Hall.

In Musical Fund Hall, a rather-small-for-a-convention building still standing at 8th and Locust Streets and now a nine-unit condominium, the Republicans nominated not a politician, but, like in 2016, a celebrity with an odd background.

John Fremont was an illegitimate son of a Southern mother and a French-Canadian father. He became an adventurer as a young man, with his friend Kit Carson taking five excursions through the new Western American lands, mapping the paths through the mountains to the sea.

Fremont wrote some pretty dry journals of his explorations, but fortunately he had married one of the belles of Washington, Jesse Benton, the daughter of the longest-standing Democratic U.S. Senator, Thomas Benton of Missouri. Jessie, the Kris Kardashian to Fremont’s Bruce Jenner, gussied up the journals and spread them around D.C. In no time, Fremont was a hero, and soon after got that Republican nomination. Fremont sometimes liked sporting his French-Canadian heritage, at times dropping the “T” at the end of his last name and inserting an accent over the “E.”

The Democrats, dissatisfied with the ineffectual, if incredibly handsome, Franklin Pierce, took 17 ballots in Cincinnati – the first convention that far west – and came around to the candidate who had been sitting around waiting it out for decades, Hillary … er, I mean, James Buchanan. Buchanan had been a Pennsylvania legislator, a member of both houses of the U.S. Congress, Minister to Russia, Minister to Great Britain and Secretary of State. Presidents Polk and Tyler had offered him a Supreme Court seat, but he just always wanted to be president.

At the long-toothed age of 65, Buchanan finally had his wish. His long experience had made him a lot of friends, but an old-timer’s view of government. He had known every president since James Madison and still wore the collars that Madisonians had. He was, though, the life of the party, so to speak, and always gave the best fetes wherever he lived. He never married, but was a marvelous dancer – the Czar’s wife’s favorite waltz partner – and storyteller, a cigar almost always in one hand and a glass of Madeira in the other.

Buchanan ran away with the election, but not after it had a few more bizarre elements. None of the candidates gave even one stump speech, supported at huge rallies by what even then were called “surrogates.” Buchanan’s brother’s wife’s brother was the Jay-Z of his age, Stephen Foster, he of “Sewanee River” and “My Old Kentucky Home.” Not that Foster ever saw the Sewanee or had a home-coming in Louisville – he was from that old Southern city of Pittsburgh, but saw a gold-mine in Southern-leaning lyrics. He was happy to lend his tunes to his in-law for his campaign, and wrote among the first presidential campaign songs. Unfortunately, the copyright laws were a bit thin in the 1850s, so the Fremont folks saw the light and wrote lyrics to Foster’s melodies, perhaps trying to make it seem like even Buchanan’s in-law didn’t support him.

On the other hand, Sen. Benton kept true to his Democratic Party, not even supporting his favorite daughter’s husband. Maybe this would be equivalent, say, to Ivanka Trump campaigning for her friend Chelsea’s mother, Hillary.

The Know-Nothings? Well, they won Maryland, the one state founded by, well, the Catholics they despised.

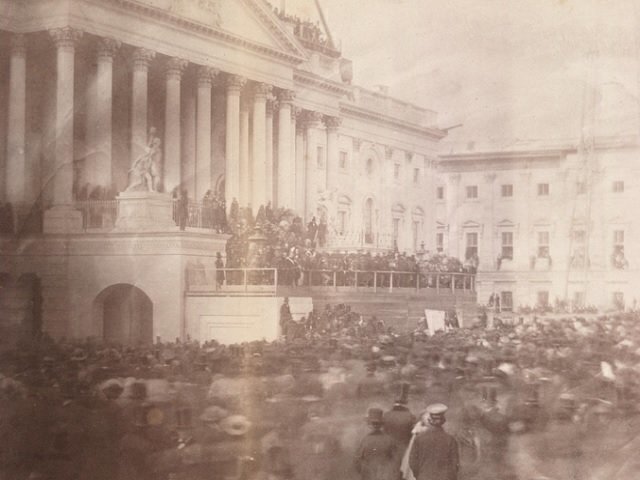

All of this laid the ground work for the Civil War, but that was still a few years off. Buchanan came to a Washington starved for happiness. From Jackson on down, each president before him had a family death – sometimes his own – either while in office, just before or just after. Buchanan’s inaugural ball was perhaps the greatest American party of the 19th century. Six thousand people showed up in a vast tent that nearly filled a park near the White House. There was a 100-piece orchestra and food and decorations that did not stint. Buchanan was said to have given $3,000 for the liquor stash, equivalent to nearly a million dollars in today’s money.

Despite the crazy campaign, Buchanan rode the early wave with vast supplies of good will.

Two days later, however, the Supreme Court decision Buchanan did so much to influence came out – the Dred Scott case. It was the first move in his slide toward “Worst. President. Ever,” but, then, that is another story.

Robert Strauss is a journalist, educator, historian and author. He will discuss his latest book, Worst. President. Ever., at the National Constitution Center on Monday, November 28 at 12 p.m. Learn more and reserve tickets.