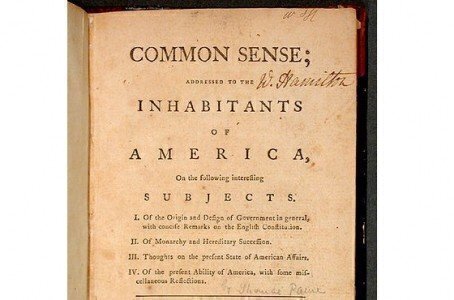

On January 10, 1776, the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense became the first viral mass communications event in America.

The first version of Paine’s pamphlet was printed just a few blocks from the current-day National Constitution Center in colonial Philadelphia in 1776, and it went viral, in the current sense of the word, when it hit the cobblestone streets here.

Common Sense sold 120,000 copies in its first three months, and by the end of the Revolution, 500,000 copies were sold. The estimated population of the Colonies (excluding its African-American and Native American populations) was 2.5 million.

An estimated 20 percent of colonists owned a copy of the revolutionary booklet. In current-day sales, that would amount to sales of 60 million, not including overseas sales. Only a handful of books have sold more than 60 million copies in the past two centuries, and those books had the benefit of modern publishing outlets and promotion.

Link: Read Common Sense

In the case of Common Sense, the publicity was spread literally through word of mouth, since people would buy the pamphlet and shout the words on street corners and inside taverns for the illiterate to hear.

Paine was born and raised in England, and he had been in Philadelphia for little more than a year, after getting a letter of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin. He published Common Sense anonymously, and its simple words made the case for the Colonies’ separation from England, in no uncertain terms.

For example, in explaining his objection to England’s constitutional monarchy, Paine says, “as a man who is attached to a prostitute is unfitted to choose or judge of a wife, so any prepossession in favour of a rotten constitution of government will disable us from discerning a good one.” The pamphlet sparked a public debate that now included most of the colonists, including those who couldn’t read or understand some of the more complicated arguments being made for freedom.

Paine’s follow-up to Common Sense was a series of pamphlets called The American Crisis. General George Washington had the first pamphlet read to his troops at Washington’s Crossing in late 1776 to convince them to extend their enlistments so he could attack Trenton.

“These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph,” said Paine.

In his later years, Paine would become a controversial figure because of his writings on religion and his role in the French revolution; only a handful of people attended his funeral in 1809.

President Thomas Jefferson had permitted Paine to return from France in his final years and wrote about the author in 1821.

“No writer has exceeded Paine in ease and familiarity of style, in perspicuity of expression, happiness of elucidation, and in simple and unassuming language,” Jefferson said. “In this he may be compared with Dr. Franklin; and indeed his Common Sense was, for a while, believed to have been written by Dr. Franklin, and published under the borrowed name of Paine, who had come over with him from England.”

At the time, it was still a crime in England to publish any sections of Common Sense.