Today, more than 60 percent of all Americans registered to vote will have cast ballots in a highly contested presidential race. But voter participation and controversy this year don’t match the drama back 140 years ago when a nation’s fate seemingly hung in the balance in one election.

On November 7, 1876, in the year of the American centennial, more than 82 percent of registered voters showed up in a record turnout to decide the fate of Reconstruction, the post-Civil War policy that dominated life in the South.

The record voter turnout for that election even eclipsed the 1860 election that set the stage for the Civil War. But few people remember the main participants in 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden, and that it took nearly four months to determine a winner – just three days before the new President was inaugurated in March 1877.

In the end, a compromise was apparently reached over disputed electors from the South and one elector from Oregon that allowed Hayes, a Republican, to become President, instead of Tilden, the Democrat who had the most popular votes in the election. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Bradley played a key role in that process, as part of an unprecedented joint commission of Congress members and Supreme Court Justices that ruled on an issue that fell outside of the Constitution.

What came to be called the Compromise of 1877 saw the withdrawal of federal troops from Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina as part of a purported bargain made by the Republicans to end Reconstruction in the South in exchange for Hayes’ election. The withdrawal then led to the imposition of segregation and voter suppression of blacks for generations, until their rights under the Constitution’s 14th and 15th amendments were upheld nearly 80 years later.

In the run-up to the 1876 election, incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant decided to not seek a third term in office. The Republican favorite to replace Grant, James Blaine, was accused of taking bribes when he was Speaker of the House and he also collapsed at a public church service. There were enough doubts about Blaine to prevent his nomination. Hayes, the reformed-minded former Ohio governor and Civil War general, was a compromise candidate.

Tilden was also a reformer who as governor of New York fought political corruption, but he also was opposed to the Radical Republicans who pushed for harsh Reconstruction terms against Southern states.

After Election Day, four states, Florida, Oregon, Louisiana and South Carolina, sent two rival slates of electors to Congress to be counted, since there were rival Democratic and Republican factions in those states. Tilden had taken 184 electoral votes and was one vote short of winning the election. It soon became apparent that the Constitution hadn’t taken into account the scenario of disputed electors at a state level, and there were disagreements about how the dispute would be settled within Congress. Also, violence about the election outcome was a distinct possibility.

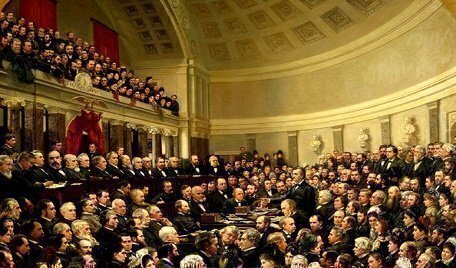

Congress did act by passing the Electoral Commission Act in January 1877 to establish a special commission of 15 people to decide the election. The commission consisted of five Senate members, five House members and five Supreme Court Justices. The House and Senate groups were split on party lines. The final and 15th vote on the commission was expected to be Supreme Court Justice David Davis, an independent.

However, Davis declined to serve on the commission when he resigned from the Supreme Court to accept a position in the Senate. His replacement was Joseph Philo Bradley, a Republican named to the Court by President Grant.

Starting in February 1877, the commission awarded all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes in a series of 8-7 votes, with Bradley voting with the Republicans. Hayes had now won the general election by one electoral vote. But the Democrats in Congress filibustered the results by offering various procedural challenges.

On Friday, March 2, 1877 at 4 a.m., the election results were officially certified after the Democrats stopped objecting. Hayes was inaugurated the following Monday. During the preceding months, political leaders worked out the Compromise of 1877 behind closed doors.

An 1887 law finally changed how Congress could settle such a dispute without invoking a special commission including Supreme Court Justices in the process. The House and Senate would each serve as a referee, with the governor of the state in dispute as a tie breaker if Congress can’t agree on which slate of rival electors to choose.