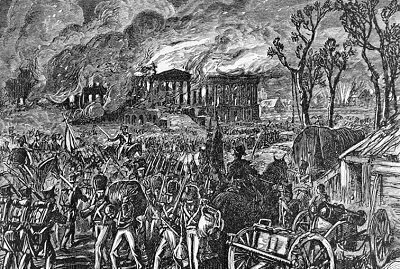

As the United States capital of Washington, D.C., burned 201 years ago today, it was an act of nature that helped to drive the British from the besieged city, and possibly save it from more destruction.

The anecdotal evidence of the tornado, which apparently touched down in the middle of the city on August 25, 1814, comes from the National Weather Service.

The anecdotal evidence of the tornado, which apparently touched down in the middle of the city on August 25, 1814, comes from the National Weather Service.

“In the early afternoon, a strong tornado struck northwest Washington and downtown," says the NWS. "The tornado did major structural damage to the residential section of the city. More British soldiers were killed by the tornado's flying debris than by the guns of the American resistance.”

The story of the brief British occupation of an undefended Washington, D.C., in 1814 is well-known. During the War of 1812, the British were urged to attack something in the former colonies after American troops attacked Canada and burned some government buildings. Washington was picked as the target because of its symbolic importance, its easy access from the sea, and the inability of American troops to defend it. President James Madison and his wife, Dolley, were aware of the threat and made prearranged plans to escape the city if and when the British attacked.

On August 24, troops from both armies met outside of Washington, and the British Army easily defeated an inexperienced volunteer American force. President Madison and Secretary of State James Monroe were nearly captured. As the British troops moved onward, Dolley Madison gathered belongings from the White House, including a copy of the iconic Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington, and fled to safety.

The British troops set fire to the Capitol, the White House and other government buildings that day. They also took time to finish off a meal at the White House before torching the building.

On the next morning, the British invaders sought out ammunition and other supplies to burn. The decision had been made to leave Washington soon, especially after an accident the previous night had led to the death of 30 British soldiers who were seeking out a gunpowder supply. There were also rumors that the Americans had amassed a much larger militia and were returning to confront the British forces.

As the British troops were finishing up their operation, there appeared on the horizon clouds that portended a violent storm. George Robert Gleig, a British soldier on the scene, detailed what happened next in his memoirs as the severe thunderstorm rolled into the city in the afternoon.

“Of the prodigious force of the wind it is impossible for you to form any conception. Roofs of houses were torn off by it, and whisked into the air like sheets of paper, while the rain which accompanied it resembled the rushing of a mighty cataract rather than the dropping of a shower,” Glieg wrote.

Glieg said the incident produced “the most appalling effect I had ever, or probably shall ever witness.”

The severe weather lasted for two hours, he said, dumping torrential rain on the city. At least two British troops were killed, and Glieg was knocked off his horse. He also said two cannons were picked up in the air and tossed around during the most violent part of the storm.

According to other accounts, part of the storm seemed tornado-like. The winds tore the roofs off the General Post Office and Patent Office buildings, and trees were uprooted.

Michael Shiner, who was then a young slave in Washington, recounted the storm in memoirs published after he had gained his freedom. Shiner said that during the event, houses were picked up by the winds and landed on their foundations.

Glieg recalled that while the rains doused the fires set by the British, they were able to use the confusion caused by the storm to cover their quick withdrawal from Washington that night.

In the storm’s aftermath and subsequent British departure, Madison and the American forces returned to Washington to see the destruction. The White House and Capitol were rebuilt, and Thomas Jefferson donated his book collection to restock the Library of Congress.

On September 1, Madison said in a proclamation that the attack showed “a deliberate disregard of the principles of humanity and the rules of civilized warfare, and which must give to the existing war a character of extended devastation and barbarism.” He also noted that the invasion happened at the same time the British invited the Americans to start peace talks.

Two weeks later, the British failed to invade Baltimore in a similar attack that is best remembered today for its connection to the nation’s anthem, "The Star Spangled Banner." Major General Robert Ross, who led the British attack on Washington, was killed by American snipers in Baltimore as the battle again.