Note: Landmark Cases, C-SPAN’s new series on historic Supreme Court decisions—produced in cooperation with the National Constitution Center—continues on Monday, Oct. 19th at 9pm ET. This week’s show features the Slaughterhouse Cases.

The originally intended meaning of various constitutional clauses is a source of constant discussion among scholars and jurists. These debates are complicated, in part, because of how long ago these clauses and amendments were drafted. Simply asking the framers is not an option.

When the Supreme Court heard the Slaughterhouse Cases in 1873, they were tasked with interpreting the meaning and scope of the Reconstruction Amendments passed after the Civil War. Although the 13th and 14th Amendments were ratified only five years earlier, the Court adopted a contentious reading of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the 14th Amendment. This interpretation altered the trajectory of constitutional law.

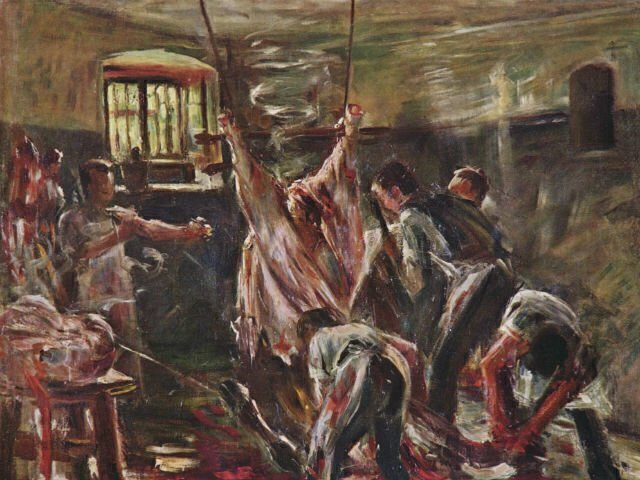

In 1869, the Louisiana state legislature granted a monopoly to the Crescent City Livestock Landing & Slaughterhouse Company, and mandated that all other livestock slaughtering businesses in the New Orleans area either shut down or pay to work on the Crescent City premises. Louisiana justified this monopoly under its police power to make laws that promote the “safety, health, welfare and morals” of its citizens. State officials explained that centralizing meat production would increase the welfare of both workers and consumers through the labor and health standards enforced at the Crescent City slaughterhouse.

Butchers in the New Orleans area objected to the mandate, saying that the law made doing business for them too costly and deprived them of their livelihoods. These butchers sued Louisiana and argued that the state-sanctioned monopoly infringed on their newly ratified 13th and 14th Amendment rights.

They argued that being forced to pay the Crescent City slaughterhouse to maintain their livelihoods amounted to involuntary servitude. Furthermore, the butchers argued that the law infringed on citizens’ “privileges or immunities” and deprived individuals of property without “due process of law.” The Court was thus asked to decide the scope and meaning of the newly passed amendments while their ratification was “fresh within the memory of us all.”

Writing for the Court, Justice Samuel Miller quickly dismissed the butcher’s claims regarding due process and involuntary servitude. He said that “under no construction” of the Due Process Clause is the Louisiana statute impermissible. He also explained that since the intention of the 13th Amendment was clearly to end African-American slavery, it would be improper to understand this alleged deprivation of livelihood as covered by the amendment.

Justice Miller then turned to the question of whether the butchers’ “privileges or immunities” were violated by the Louisiana statute. For guidance, Justice Miller looked to Article IV, which entitles “the Citizens of each State” to “all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.” The 14th Amendment, on the other hand, guarantees protection of the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” [emphases added]

Miller reasoned that the two clauses protect different bundles of rights, with Article IV protecting the rights of state citizenship and the 14th Amendment protecting rights of national citizenship. The privileges and immunities of U.S. citizenship are narrow and only those specified in the Constitution, which include the right to freely travel throughout the states. Not included, Miller explained, is the right to one’s livelihood or be protected against a monopoly.

Through this narrow reading, Justice Miller effectively rendered the Privileges or Immunities Clause impotent—despite the fact that its drafter, Representative John Bingham of Ohio, had explained on the House floor that the clause was meant to give Congress the power to enforce the Bill of Rights against the states. Later, in Adamson v. California, Justice Hugo Black wrote that the historical record was clear that Bingham’s intention was to ensure that state governments could not violate the rights outlined in the first ten amendments.

By ruling that the 14th Amendment does not protect substantive rights, constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe has argued, the Court “incorrectly gutted” the Privileges or Immunities Clause. His colleague Akhil Amar has echoed that assessment, declaring that “virtually no serious modern scholar—left, right and center—thinks that [Slaughterhouse] is a plausible reading of the [14th] Amendment.”

As a result of the Slaughterhouse Cases, the butchers in New Orleans were forced to deal with the monopoly granted to Crescent City Livestock. But the lasting outcome was a limited understanding of the Privileges or Immunities Clause. Instead, citizens would have to seek substantive rights protection under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause—a strategy that continues today.

Jonathan Stahl is an intern at the National Constitution Center. He is also a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in politics, philosophy and economics.