On July 21, 1925, the famous Scopes Monkey trial over teaching evolution in public schools concluded. Mostly remembered today was the clash between two legendary public figures. But the legal fight didn’t end that day in Tennessee.

Eventually, the Supreme Court settled many of the issues about the Scopes case in 1968, in a decision called Epperson v. Arkansas. A unanimous Court ruled on the legality of a 1928 Arkansas law that barred teachers in public or state- supported schools from teaching, or using textbooks that discussed human evolution.

Eventually, the Supreme Court settled many of the issues about the Scopes case in 1968, in a decision called Epperson v. Arkansas. A unanimous Court ruled on the legality of a 1928 Arkansas law that barred teachers in public or state- supported schools from teaching, or using textbooks that discussed human evolution.

A teacher in Little Rock, Arkansas had been given textbooks from her administration that taught evolution, and she sought out court guidance about her situation.

Justice Abe Fortas, writing the main opinion in the decision, spoke for seven Justices in stating that the Arkansas law violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

"The State's undoubted right to prescribe the curriculum for its public schools does not carry with it the right to prohibit, on pain of criminal penalty, the teaching of a scientific theory or doctrine where that prohibition is based upon reasons that violate the First Amendment,” Fortas said.

Two other Justices said the law violated the 14th Amendment ‘s Due Process clause or the First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause.

Fortas referenced the Scopes case in the first paragraph of his opinion, noting that the Arkansas law was based on Tennessee’s “monkey law,” and that Tennessee Supreme Court eventually tossed aside the verdict reached against John Scopes in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925, in the case, which was called Scopes v. State.

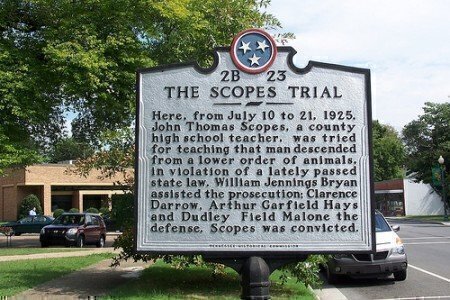

In the Scopes case, high school biology teacher John Scopes was charged with illegally teaching the theory of evolution in violation of a state law championed by William Jennings Bryan.

The charismatic Bryan was a three-time presidential candidate for the Democratic Party, a former Secretary of State, and widely known orator. In his later years, Bryan led a movement to have the Darwinian evolution theory barred from classrooms.

In March 1925, the anti-evolution group had its first big success when Tennessee Governor Austin Peay signed the first law in the United States to ban the teaching of evolution. The American Civil Liberties Union soon sought to challenge the law in court.

The town of Dayton then approached both sides and offered to host the trial, seeking to gain national publicity. That came quickly when Bryan agreed to argue the prosecution’s side in person, and two famed attorneys agreed to represent Scopes.

Clarence Darrow was the nation’s most famous defense attorney and his co-counsel was Dudley Field Malone, another noted attorney.

The 11-day trial was broadcast live on the radio, a first for that medium, and it generated an enormous amount of national attention. The noted journalist H.L. Mencken covered the affair, coining the phrase “monkey trial” and other terms that became part of the trial’s lore.

During the testimony, Darrow referred to the First Amendment in his opening remarks, arguing that the Tennessee law violated the Constitution’s Establishment clause. Seven days later came the famous two-hour confrontation between Bryan and Darrow over religion, when the trial was moved outside because of the summer heat. The next day, it took the jury nine minutes to convict Scopes. The judge fined Scopes $100, and the ACLU said it would appeal the decision.

After the verdict was read, Scopes spoke for the first time at the trial, defending his decision to pursue the case.

“Any other action would be in violation of my ideal of academic freedom — that is, to teach the truth as guaranteed in our constitution, of personal and religious freedom,” he said.

Five days later, Bryan died after suffering a stroke while he was staying in Dayton. In January 1927, the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the Scopes decision on a technicality, but it insisted the state law was constitutional that barred teaching evolution in public school classrooms.

The Supreme Court’s Epperson decision ended part of the argument over teaching evolution in the classroom, but in later years, the debate has shifted to the right to teach creationism in publicly funded schools.

The Court has ruled twice that state laws requiring public schools to use a "balanced treatment" to teach creationism and evolution were unconstitutional.

Another debate is over the proper teaching of the theory of “intelligent design,” which states that an intelligent designer must have played a role in the creation of man and the world.

In 2005, a federal judge based in Pennsylvania held that teaching intelligent design violated the First Amendment’s Establishment clause. U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III said, “the overwhelming evidence at trial established that ID is a religious view, a mere re-labeling of creationism, and not a scientific theory.”