The Supreme Court, showing once again its reluctance to take a bold step to put some limits on the decades-long practice of “partisan gerrymandering,” voted on Monday to keep the courthouse doors open to challenging the practice and edged a bit closer to a definition of the constitutional harm it may cause.

While four of the nine Justices tried to widen the impact of the most important of two rulings by arguing that broader remedies could be found when legislative district lines are skewed to favor one party, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., bluntly countered that his main opinion was the only one that spoke for the Court. “The reasoning of this Court …is set forth in this opinion and none other.”

While four of the nine Justices tried to widen the impact of the most important of two rulings by arguing that broader remedies could be found when legislative district lines are skewed to favor one party, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., bluntly countered that his main opinion was the only one that spoke for the Court. “The reasoning of this Court …is set forth in this opinion and none other.”

The Court has been thinking and writing about the partisan gerrymandering question for 45 years but has never come up with the formula for judging when it would be unconstitutional. Again on Monday, it said it had not come up with such a formula.

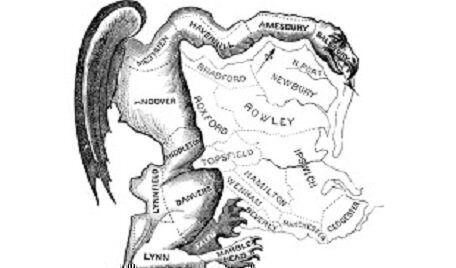

But two aspects of the decision – unanimous on all points except what should happen next in a Wisconsin case, decided along with a narrower but unanimous ruling in a Maryland case – might encourage the foes of the practice that dates back to the early 1800s and Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry (from whom the practice got its name).

First, the entire Court signed onto the conclusion that a voter can at least file a lawsuit if they have a claim that that voter’s own election district was drawn in such a way that diluted that individual’s vote – in other words, caused that voter the individual, personal harm of making his or her vote less effective in choosing candidates of the party they favor.

Second, the majority – over two Justices’ dissents – did not dismiss the Wisconsin case outright even though it ruled that the individual voters had not made their case. Instead, it sent the case back to a special three-judge trial court to allow them a new chance. (It was this continuing lawsuit that the Court’s four more liberal members sought to influence toward a wider outcome – a statewide remedy for partisan-driven district maps.)

The first part was probably the most important, because it at least identified a legal theory – one that it has used for years to limit the use of racial gerrymanders in districting – that was a plausible basis for going after partisanship. While saying it was not spelling out what the test of dilution would be, this was the first time that the full Court had lined up behind a theory of dilution in the partisan realm. In racial gerrymandering cases, it has said repeatedly that it is unconstitutional if a new election map is the “predominant” result of racial factors. If it embraced that idea in the partisan context, it conceivably could adopt a similar standard.

There was one part of the new ruling, in the Wisconsin case, that was a major blow to challengers to partisanship in districting: The Court said that voters would not even be allowed to enter federal court if their claim was that they had lost political influence statewide as a result of a partisan map. The kind of legal injury it made clear it is willing to let voters claim is only the personal harm to their own vote. Only if they do get into court on an injury claim limited to them and win on that claim could they then try to get a statewide remedy, perhaps along the lines of the four liberals’ opinion Monday, written by Justice Elena Kagan.

The courts’ battle over partisanship in districting continues to be an active one, and the Justices now have two options, at least, on what to do next. If they want to return to the controversy next term, they already have awaiting them on their docket a case from North Carolina that some analysts say raises a more compelling challenge to a partisan map, and they could grant review of that. It is too late to hear it in the current term, likely ending this month.

If the Justices want to wait to see how the Wisconsin and Maryland cases come out after their return to lower trial courts, they have that option. That could take some time, however, so the unsettled issues over the practice could continue months beyond this year.

One thing, though, is clear as of Monday: the 2018 elections will go forward without any new clarity from the Supreme Court on the constitutionality of partisan-drawn districts. But in at least one state – Pennsylvania – the election of members of Congress from that state will go forward using a map drawn by the state’s supreme court to overcome partisan gerrymandering; the new map strongly points toward a pickup of seats by Democrats.

The Court had taken on the Wisconsin and Maryland cases this term to return to a constitutional controversy that they had first encountered in 1973. Several times since then, it had said that it was not ruling out lawsuits against partisan-drawn districting, but each time it said it had not yet found a manageable legal standard to apply.

The two cases had appeared to be solid tests on the practice, because the Wisconsin plan was drafted by Republicans and it worked, in election after election, to give their party more seats in the state legislature than represented their share of the statewide vote count for all candidates, and the Maryland plan was drafted by Democrats for a single congressional district in the western part of the state, and it worked, in repeated elections, to lead to victory for a Democratic candidate after decades of winning Republican candidates.

The Wisconsin case (Gill v. Whitford ) was sent back to a federal trial court on Monday, for another look. In the Maryland case, the Court did no more than rule that a federal trial court had not been wrong when it refused to block the Democratic plan because, among other reasons, that court wanted to await the Supreme Court’s coming decision in the Wisconsin case.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the opinion in the Wisconsin case, joined by all of the other Justices on the points that the individual voters had not proved that they legally were in court. Two Justices – Clarence Thomas, joined by Neal M. Gorsuch – did not join in the order to return the case, arguing instead that the case should be dismissed outright now.

Justice Kagan’s separate opinion in that case was joined by Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor. Those four had also signed onto the main opinion by the Chief Justice.

The brief, five-page ruling in the Maryland case (Benisek v. Lamone) was issued in the name of the full Court (“per curiam”) and there were no indications of any dissent.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.