* Editor’s Note: This post is part of a symposium commemorating the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Loving v. Virginia. Other contributions come from Ken Tanabe and Serena Mayeri.

* Editor’s Note: This post is part of a symposium commemorating the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Loving v. Virginia. Other contributions come from Ken Tanabe and Serena Mayeri.

To explain the history of racial laws and practices essential for understanding the landmark Supreme Court case of Loving v. Virginia (1967), you have to go back all the way to the colonial period in American history. In 1691, the royal colony of Virginia was among the earliest of the British colonies in North America to attempt to regulate marriage and sexual contact between white colonists and any people of color (“negroe, mulatto, or Indian” as the statute put it). The irony is that this first Virginia law on the matter did not explicitly prohibit such unions, but instead threatened all interracial spouses with permanent banishment.[1]

Sadly, of course, that’s exactly what the judge in Caroline Country, Virginia tried to impose as a punishment on Richard and Mildred Loving when they appeared before his court in 1959. They were told that in order to avoid prison, they would have to leave the state for 25 years and that they could only return to visit family if they did so separately.

On the question of interracial marriage, American law has evolved in a complicated fashion, mostly tied up in the bitter politics of slavery and its legacy. When Pennsylvania passed its gradual abolition act in 1780, for instance, it also became the first state to repeal a previous ban on interracial marriage. Some free states, like Vermont, never allowed slavery and also never imposed any color restrictions on marriage.[2] Yet there were also several former slave states, like Virginia, that continued to regulate the prospect of marriage across color lines well into the twentieth century. These “modern” prohibitions were initially part of attempts during the Reconstruction period after the Civil War to segregate newly freed blacks from white society, especially in the former Confederate states, but also in the handful of former Union slave states. By the 1890s, these various segregationist laws and practices came to define for most Americans the “Jim Crow” South.

But the movement to stop interracial marriage gained a new and broader dimension in the 1920s with the growing global popularity of eugenics, or what is now acknowledged as the pseudoscience of improved human breeding. Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 was a by-product of this craze for eugenics. The statute reaffirmed the traditional Reconstruction-era state ban on interracial marriage, but now also carved out an exception for marriages between whites and those “with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian." This was considered by some as progress, at least compared to the original standards of 1691.

It should be noted that over the years these various state marriage laws, from all eras in American history, have usually been termed anti-miscegenation statutes. But that term itself was not coined until the Civil War, when it was invented by Northern Democrats for political purposes and put to use in the 1864 presidential election. It was the name of a phony pamphlet that appeared to promote race-mixing as a scientific endeavor. Democratic operatives then distributed this hoax (or what might be considered a pioneering example of “fake news”) to leading Republicans and even President Abraham Lincoln asking for their endorsements. Lincoln declined to respond, but some others did, and the pamphlet became a source of bitter controversy in the campaign.[3]

Under the doctrines of American federalism, marriage is a subject normally reserved for state law, but the U.S. Supreme Court did address itself to the particular topic of interracial marriage or sexual relations on occasion. The most infamous statement by the court on this issue came from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in the majority opinion for the Dred Scott case (1857). While explaining how blacks could not be considered citizens under federal law, Taney pointed to the American traditions against “intermarriages between white persons and negroes or mulattoes,” which he called “unnatural and immoral.”

After ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868), the Supreme Court began to rule on equal protection matters as they applied to interracial marriage and sexual relations. The most notable decision came in Pace v. Alabama (1883), when the court ruled that since the punishment under Alabama state law for each participant in a mixed-race sexual relationship was the same, regardless of their color, then there was no equal protection violation in the case before them. In other words, the state statute was considered constitutional because it was equally cruel to both whites and blacks.

There were other major interracial marriage and sex cases between Pace and Loving, but some of the most important turning points in the fight for marriage equality involved criminal justice and not domesticity. In Powell v. Alabama (1931) and Norris v. Alabama (1935), for example, the Supreme Court tried to establish some procedural protections for nine black youths, the so-called “Scottsboro Boys,” who had been falsely accused of raping a white woman. This federal intervention did little to help those black defendants, however, who were subsequently retried in state courts. Nonetheless, it did begin to turn the legal tide at least on the matter of equal protection and civil rights.

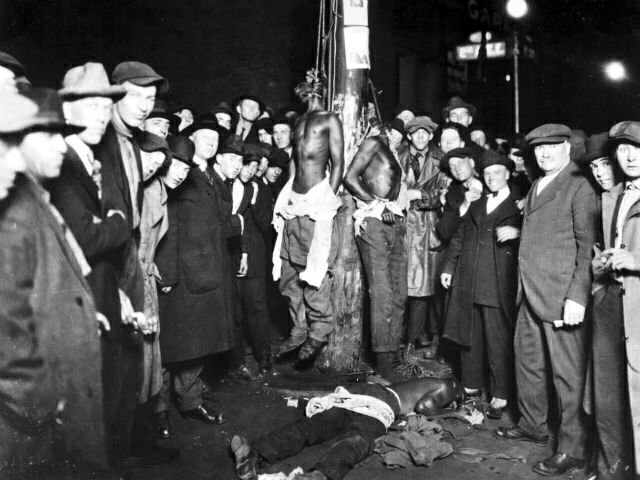

Yet no historical discussion of the Loving case can ignore the other type of law that always mattered in cases like these. First, there were state laws. Next there was at least the hope of the U.S. Constitution and its promised individual protections. But lurking behind all of it was what people in the Jim Crow South labeled the “lynch-law.” Lynching, or extra-judicial violence, was the punishment of choice in hundreds, perhaps thousands, of cases of interracial contact, sex, and even marriage. Most lynching occurred in the former slave states, but there were cases in the North as well. The latest scholarship suggests that there were nearly four thousand documented lynching episodes in the American South alone between the 1870s and 1950s.[4]

When Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving married in Washington, DC, in June 1958, they were doing so less than three years after young Emmett Till had been brutally killed for simply flirting with a white woman in Mississippi. Till’s violent death ultimately became one of the key turning points in the struggle for civil rights. But when the Lovings first entered the Virginia judicial system in 1958 and 1959 for the simple act of marrying, his death stood before them as a dire warning. They knew that they had to concern themselves with much more than a dry understanding of the laws. They also had to worry about what might lurk behind any attempt to challenge these statutes or the arbitrary customs and practices that had shaped them so awfully for hundreds of years.

Matthew Pinsker is Associate Professor of History at Dickinson College.

[1] One of the best online introductions to the history behind the Loving case comes from its entry in the Encyclopedia of Virginia, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Loving_v_Virginia_1967

[2] According to a 2013 online exhibit from the Library of Virginia, there are ten states that never had bans on interracial marriage: Alaska, Connecticut, Hawaii, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Vermont was also the first state to allow civil unions for gay couples in 1999. See “You Have No Right: Law and Justice; The Road to Loving v. Virginia,” http://www.virginiamemory.com/exhibitions/law_and_justice/road-to-loving

[3] For more details on the origins of “miscegenation” as a term, see Harold Holzer, “How a Racist Newspaper Defeated Lincoln in New York in the 1864 Election,” The Daily Beast, May 5, 2013, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/05/02/how-a-racist-newspaper-defeated-lincoln-in-new-york-in-the-1864-election

[4] The Equal Justice Initiative has mapped nearly 4,000 lynching cases across the American South. Other organizations, such as Monroe Work Today, have detailed over 5,000 such lynching episodes from the 1830s to the 1960s, across the entire country. For more details, see the Legacy of Lynching Syllabus from the House Divided Project at Dickinson College, https://storify.com/HouseDivided/lynching-syllabus