This week, Republicans leaders reportedly engaged in a brief debate about killing the Senate filibuster in a closed-door retreat in Philadelphia. That discussion could intensify as the GOP moves to approve a Supreme Court nominee and new legislation in the Senate.

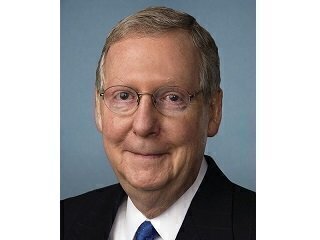

Politico said on Wednesday two House Representatives, Trent Franks and Bruce Poliquin, pressed Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on the Senate’s reluctance to kill the filibuster entirely, after former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid killed much of it in 2013.

Politico said on Wednesday two House Representatives, Trent Franks and Bruce Poliquin, pressed Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell on the Senate’s reluctance to kill the filibuster entirely, after former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid killed much of it in 2013.

The Senate’s remaining filibuster rules require a cloture vote by 60 Senators to end debate on proposed Supreme Court nominations and legislation. Reid’s parliamentary move in 2013 killed the filibuster for federal judicial and executive-office nominees.

McConnell reportedly was non-committal at the meeting, but back in November, he told the press that Senate rules changes need to be taken seriously. “Frequently new majorities think it’s going to be forever. Nothing is forever in this country," he said. "We’ve been given a temporary lease on power, if you will. And I think we need to use it responsibly."

But some political observers think that the upcoming Senate debate over President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee could force the issue. (The questions on the filibuster on Wednesday were related to legislation stalled in the Senate by cloture rules.)

Representative Poliquin spoke with Politico after the meeting and said if the filibuster remained in place, Senators who invoked it should be forced to take the Senate floor and keep it, in an old-style type of filibuster. Representative Jeff Duncan also said he’d like to see a filibuster proponents take the floor “like Strom Thurmond did” and hold it for about 24 hours, said Politico.

The filibuster in its original form dates back to the 1830s and it allows a Senator (or a group of Senators) to delay a vote by taking the Senate floor and physically holding it as long as possible. The House got rid of its version of the filibuster in 1842. (The filibuster itself is not in the Constitution; it is a rule established by Congress under its Article I rule-making powers over its own sessions.)

“Talking filibusters” are rare nowadays because the Senate changed its rules to allow for “silent filibusters.” This happens when a Senator tells his or her floor leader that they wish to filibuster a vote. At that point, at least 60 Senators have to agree to override the filibuster in a cloture vote.

A test for the filibuster could come with the Supreme Court nominee vote on the Senate floor, if Senate Republican leaders can’t get eight votes from Democrats to reach the 60 votes required. Under the Constitution, the President nominates a Supreme Court candidate to the Senate for confirmation. Once the nomination is approved by and sent to the entire Senate for a floor vote, a simple majority is needed to confirm the nominee. However, 60 votes are needed under cloture rules for the nomination to make it to the floor.

President Donald Trump has told Fox News that he would encourage McConnell to eliminate the filibuster of Supreme Court nominees, if needed.

The significance of changing the filibuster rule could be far-reaching and politically volatile, but filibusters against Supreme Court nominees are rare. In 2006, a brief, failed effort was launched against Samuel Alito’s nomination that included Senator Barack Obama. In 1968, a successful effort was made against Abe Fortas’s nomination to Chief Justice that may have been a filibuster.

The elimination of the legislative filibuster also could be in play if some of the Republicans’ proposed laws related to health care and taxes don’t fall within the Senate’s reconciliation process, which only requires a simple majority vote.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.