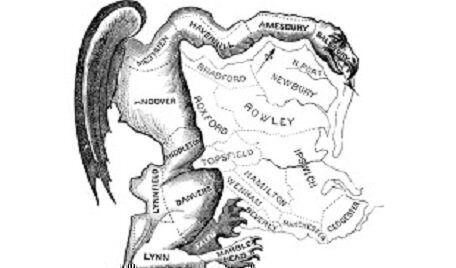

The campaign to end partisan gerrymandering of seats in Congress and state legislatures, an effort that began a half-century ago, could, at last, be on the edge of triumph or defeat this week in the Supreme Court.

Two cases up for hearings on Tuesday could be the ultimate tests of the practice, as old as the Republic itself, of drawing election districts to favor the candidates of one party and dim the chances of their rivals in the other party.

Two cases up for hearings on Tuesday could be the ultimate tests of the practice, as old as the Republic itself, of drawing election districts to favor the candidates of one party and dim the chances of their rivals in the other party.

Both cases involve districts for electing members of the U.S. House of Representatives, but the constitutionality of partisan-driven gerrymanders for state legislatures is at stake as well.

And if defeat is the fate handed down by the Supreme Court when it actually decides in a few months, the question then would emerge: Is there another way to take partisanship out of dividing up lawmakers’ seats? There is, but there may be trouble ahead for that, at least when it involves drawing new lines for congressional districts.

As the Court reopens the partisan gerrymander controversy, just eight months after its last review ended without a definite answer to the constitutionality question, it is too much to say that the outlook is predictably negative for the challengers.

In fact, the challengers go into Tuesday’s encounter with enthusiasm and high hopes, satisfied that their opposition to the partisan practice is catching on across the nation. They do have some significant evidence of that, in a wave of successes with voters agreeing to hand over the task of redrawing election districts to non-partisan commissions or boards. The Supreme Court allowed that approach four years ago for congressional districting, but that ruling may now be vulnerable if newly tested in the future before this changed Court.

For right now, one sign of potential trouble for the challengers could be visible the moment the Justices enter the chamber and take their seats on the bench at 10 a.m. Tuesday. That will be the absence of Anthony M. Kennedy, the now-retired Justice who for the past three decades had kept alive the prospect that, one day, the Court would be able to fashion a constitutional formula for deciding that partisanship had gone too far in the process of drawing new boundary lines for election districts.

No one knows where Kennedy’s successor, first-term Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, might stand on partisan gerrymandering but few observers think it likely that he would continue Kennedy’s cause. And it thus is not out of the question that he and four other conservative Justices would wind up as a majority to say that there can be no constitutional measure that would work, or else to fashion a test so deferential to political options as to leave the practice unchallengeable as a real-world matter.

The Court has been asked directly, in the first of the two new cases (a case from North Carolina), to rule that there is no role for courts to play in overseeing partisan gerrymandering because there simply cannot be a workable formula for judging its validity. A workable formula, of course, is exactly what has eluded the Court since its first partisan gerrymandering decision in 1973.

It is likely that the Justices will be closely divided as they ponder that issue anew in the North Carolina case and in a second case, from Maryland. That could mean that Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., may hold the deciding fifth vote and could use it to make a majority along with four conservative colleagues. Robert, at a hearing last term on the controversy, told a lawyer who was spelling out a proposed constitutional formula: “The whole point is you’re taking these issues away from democracy and you’re throwing them into the courts, pursuant to [what] I can only consider sociological gobbledygook.”

(That case, Gill v. Wisconsin, ended with a decision that avoided the question of how to judge partisan gerrymandering, with the main opinion written by the Chief Justice. The decision specified that the challengers had not aimed their legal protest at the lines of their own districts, but instead had aimed at gerrymandering statewide.)

The view that the Court should stay out of this field altogether does start with one almost-certain vote on the Court: that of Justice Clarence Thomas. He joined in an opinion in a 2004 case arguing that challenges to partisan gerrymandering had no business being in the courts at all (Vieth v. Jubelirer). That view did not have majority support then, though. In fact, the Court in 1986 in Davis v. Bandemer had ruled clearly that the courts would be open to lawsuits against partisan gerrymandering, and it has never abandoned that view.

Another member, Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., at the hearing last term in the Wisconsin case pointedly asked the lawyer for the challengers: “Is this the time for us to jump into this?” He wondered whether “there has been a great body of scholarship that has tested” one of the partisanship-judging formulas that has lately emerged. He suggested there was ongoing ferment among scholars on the point, implying that it may be too soon to settle on one approach.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, another member of the conservative bloc, displayed a good deal of skepticism in the Wisconsin case hearing, and in the end voted with Thomas to throw that case out of court entirely, without a new chance to revive it – opposite to what the majority had done.

If Justices Thomas, Alito and Gorsuch are not ready to embrace a constitutional formula, that enhances the positions that the Chief Justice and Justice Kavanaugh decide to take. That could mean that the Chief Justice, who has publicly argued that the Court should not be seen as a political institution, might not be ready to cast the vote that left gerrymandering entirely to the politicians.

Indeed, the Chief Justice remarked during the Wisconsin hearing that there was a risk that court rulings on partisan gerrymandering might appear to the public as partisan-driven.

In this regard, the Court has already made a gesture to try to demonstrate that its review of the controversy this term will not be itself a partisan exercise. It specifically accepted review of a map that clearly favored Republican candidates for Congress in North Carolina, gave an answer to and a map that clearly favored a Democratic candidate in one congressional district in Maryland. Those cases will be heard back-to-back on Tuesday.

The Court’s four more liberal members – Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor – are undeniably favorable toward the challengers; Breyer and Ginsburg, in fact, have been solidly on the side of the challengers for 15 years. Kagan wrote a separate opinion last term in the Wisconsin case that was sharply critical of partisan gerrymandering. Her opinion was joined by the other three who generally vote with her in cases that divide the Court deeply along ideological lines.

It is always possible, of course, that the outcome of the North Carolina and Maryland cases would not be a final defeat for the challengers of the partisan practice, but something short of that, still without settling on a constitutional formula. That could leave the fate of those two maps in legal limbo, with the larger constitutional issue still open.

Any ruling in the case would be of most significance to state legislatures after they return to the task of changing election district boundaries after the 2020 census; each census tends to show the movement of people, making it regularly necessary every ten years to craft new maps.

Whatever the outcome of the two new cases this term, the Court in the not-distant future is likely to be faced with the return of another partisan gerrymandering dispute: a test of whether states can constitutionality take the task of redistricting election boundaries for the U.S. House of Representatives entirely away from the state legislatures. The Constitution’s Election Clause, Article I, Section 4, specifies that “the times, places and manner of holding elections” for members of the U.S. House “shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof.”

Four years ago, in the case of Arizona Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, the Court answered what Article I meant in assigning the congressional election task (including redrawing districts) to “the legislature.” In a 5-to-4 decision, the Court ruled that the people of Arizona, when they adopted a new plan to shut out the state legislature from any role in congressional redistricting (as a way to cure partisanship), the people themselves were acting as the legislature for that purpose.

That ruling was written by Justice Ginsburg. It had the support of her current colleagues, Justices Breyer, Kagan and Sotomayor. But, significantly, it also had the support of then-Justice Kennedy, now replaced by Justice Kavanaugh.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote a lengthy and strongly-worded dissenting opinion, arguing that legislature meant legislature. His opinion had the support of two of his current colleagues, Justices Alito and Thomas. It also was signed by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who has now been succeeded by Justice Gorsuch.

Among the new non-partisan redistricting entities that are being created in an increasing number of states, nine states have assigned the primary task of drafting congressional election districts to new boards or commissions. Some of those don’t shut out the legislature entirely, giving it some role in selecting commission or board members.

A longer list of states now uses independent and mostly or entirely non-partisan boards or commissions to handle the task of shaping election districts for their state legislatures. Even if some of those exclude any role for the legislature, it is not clear that Article I’s Elections Clause would make doing so unconstitutional because that Clause only applies directly to congressional elections.

State legislative districting practices, though, still can be judged under federal voting rights laws and under the Constitution’s guarantees of voter equality, such as “one-person, one-vote.” What the Supreme Court says in the new cases being heard on Tuesday, on partisan gerrymandering as a constitutional question, would also apply to redistricting of state legislatures that are challenged as the result of partisanship.

After Tuesday’s hearing, it may take as long as three months for the Justices to reach a final decision.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.