Constitutional questions, some subtle and some obvious, some familiar and some unusual, very likely will shape how the Supreme Court on Tuesday looks at the high-stakes fight over the 2020 census, and could also be a major factor when the Justices ultimately decide. Also lurking in the background, but not yet before the Court, is a claim of unconstitutional racial bias against immigrants, aimed at President Trump, former White House advisers, and a Cabinet secretary.

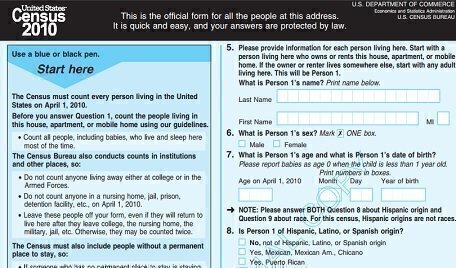

The constitutional complexity of the case, coming up for hearing Tuesday (the next to last day of hearings the Court will hold this term), arises out of the basic issue that is at stake: would it be illegal or unconstitutional for the Census Bureau to ask everyone living in America next year about their citizenship?

The constitutional complexity of the case, coming up for hearing Tuesday (the next to last day of hearings the Court will hold this term), arises out of the basic issue that is at stake: would it be illegal or unconstitutional for the Census Bureau to ask everyone living in America next year about their citizenship?

The hearing is an expanded one, set to last 80 minutes, compared to the usual one hour. Another unusual feature will be that a lawyer for the Democratic-controlled U.S. House of Representatives will be one of the four attorneys arguing. The House will line up with the challengers of the citizenship question.

The Trump Administration has been aiming, since soon after it came into office, to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census questionnaire that will go to every household in the nation, with the occupants legally required to fill it out truthfully.

The census case is the most significant test of a Trump Administration policy to reach the Court since a divided Court upheld the government policy to sharply reduce the number of foreign nationals entering the United States from Muslim countries. The census decision at issue ultimately would have its most impact on immigrants, just as the entry limitations did.

Two former advisers to President Trump, ex-White House aide Steve Bannon and unofficial adviser Kris Kobach, were involved early in the process of persuading Commerce Secretary Wilbur L. Ross (who oversees the census) to add that question to the 2020 questionnaire. Kobach has long argued that the nation should not count immigrants living illegally in the country, contending that they are not actually residents. President Trump has contended that undocumented immigrants illegally seek to vote. (The racial bias claim that, for now, is only in the background is also aimed at Secretary Ross for his role, and at President Trump for public statements hostile to immigration. So far, only one lower court has decided that claim, and denied it.)

The mandate of the Constitution’s Article I, to conduct an “actual enumeration” of U.S. population every 10 years, has long been understood to mean that everyone living in the country when the census is taken must be counted, whether citizen or not, whether legally in the U.S. or not, of whatever race or nationality.

Some experts on the census have calculated that, if the citizenship question is asked, it may reduce the actual count of the U.S. population by some 6.5 million people – an “under-count,” if it does happen, that would cause some states – especially California – to lose some of their seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. A number of states will also lose some of their shares of more than $700 billion of federal funds that are distributed to the states each year. (Both the allocation of House seats and the distribution of those funds are based on each state’s population, as found in the census.)

The basic theory of challengers to a citizenship question is that the under-count is a predictable result because households occupied by Hispanics and undocumented immigrants will refuse to fill out the questionnaire for fear that it could lead to the deportation of family members.

Three federal trial judges, in California, Maryland and New York, have accepted that theory and each has blocked the government from asking the question next year. All three judges ruled that the addition of the question is illegal under two federal laws – one governing the census and one governing how federal policy is made by U.S. agencies.

Two of the three judges have also ruled that the question would violate the constitutional mandate for an “actual enumeration,” because of the under-count that the judges agreed would result. One of those judges rejected the racial bias claim. The third judge rejected the constitutional claim under Article I.

The Trump Administration has taken the New York case to the Court, and the Justices took steps to require lawyers involved to argue that case as a test of the Article I issue as well as of the validity of the citizenship inquiry under the two federal laws. (The racial bias claim that is a part of the Maryland case will not be part of the Tuesday hearing, because that case has not yet been filed at the Court by the Administration, although it plans to do so. The Administration has taken the California case to the Court, but it is on hold awaiting the New York case’s outcome.)

The Court is reviewing the issue on an expedited basis because the Census Bureau has said it needs to know by the end of June what to include on the 2020 questionnaire.

The non-constitutional questions before the Court are keyed to the claim that two federal laws were violated when Commerce Secretary Ross decided to add the citizenship question to next year’s census. Under the Census Act, the issue is whether Ross followed the procedures spelled out by Congress on how the census is to be conducted and when a new question can be added. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, the issue is whether Ross acted “arbitrarily” by basing his decision on his belief that citizenship data was necessary to help the government enforce voting rights laws when that allegedly was only a “pretext” for his desire to assure an under-count of Hispanics and non-citizens.

The Administration is relying quite heavily upon a claim that Ross was merely reviving a long-standing practice of asking about citizenship as part of the census, going back to its early days under the Constitution, and only abandoned after the 1950 census. A group of scholars who specialize in census history and statistics studies has entered the case as a friend-of-the-court to dispute that claim, providing a historical account that suggests that the census has never directly asked everyone in the nation about citizenship.

The constitutional questions that are at issue include not only the Article I issue over what is required for an “actual enumeration,” but also the fundamental question of whether the Court even has the authority under the Constitution’s Article III to decide the case, and the implied Article III question of whether any formula can be devised by a court to judge what kind of questions are proper to ask on the census form.

The Trump Administration has argued that the challengers had no right even to sue over the citizenship question because they cannot show that they would be injured in a legal sense by its inclusion. If there is an under-count, according to this argument, it would be caused not by the government having asked about citizenship, but by the illegal act of households failing to fill out the form. Lacking such injury, this point goes on, the challengers have not brought an actual “case or controversy” as Article III requires for federal courts to be authorized to decide a case. Thus, the argument concludes, the Court should dismiss the case outright for lack of “standing.”

The challenging states and local governments and private groups counter that they would be injured by an under-count because it would take away House seats or diminish their shares of federal funds.

The Administration has argued that Congress wrote the Census Act in such a way that the Commerce Secretary has wide discretion to decide how actually to do the enumeration, and the Secretary’s use of that discretion is insulated almost completely from review by the courts. This becomes a constitutional argument based on the further assertion – related to the scope of judicial power under Article III -- that there is no way courts can figure out whether the Secretary has properly chosen to add a question to the census form, so a decision to do so must be left undisturbed. Added to this is the related argument that the Secretary’s view must prevail if he sincerely believed that he was acting for the reason he spelled out, and courts should not be looking for an illegal or hidden motive.

The challengers counter that the Census Act has very specific procedures that the Secretary must follow when he uses the discretion given to him, and that courts clearly have found – as in these new cases – that there are valid legal measures of when that discretion is misused in a way that violates the Article I command for an “actual enumeration.”

Given the Court’s usual approach of leaving constitutional questions undecided, if there is a non-constitutional way to decide a case, there may be some doubt that the Court would decide the ultimate “actual enumeration” question if it were to rule that the Commerce Secretary had violated either the Census Act or the Administrative Procedure Act. Such a finding based on a federal statute would end the case, blocking the citizenship question next year.

But, as indicated, even answering the statutory issues would draw the Court at least into some review of the scope of its Article III powers – that is, is there an actual legal controversy, and, if so, can a court fashion a way to decide it?

If the Justices were to find no violation of either federal law, it would then have to decide the “actual enumeration” question in order to settle how the Census Bureau drafts the questionnaire.

Because the case is being argued so late on the calendar of this term’s hearings, and because it is so complex in scope, the Justices will have to move with dispatch to decide it in time to guide the Census Bureau.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.