A few years ago, a group of Iowa Republicans claimed the legitimate 13th Amendment to the Constitution was “missing.” The debate is part of a historical detective story with some surprising twists that is still taking place.The Daily Beast did a fairly extensive feature on the missing amendment in 2010, which didn’t feature a cloaked Freemason stealing the amendment because it had a secret treasure map printed on it.

A few years ago, a group of Iowa Republicans claimed the legitimate 13th Amendment to the Constitution was “missing.” The debate is part of a historical detective story with some surprising twists that is still taking place.The Daily Beast did a fairly extensive feature on the missing amendment in 2010, which didn’t feature a cloaked Freemason stealing the amendment because it had a secret treasure map printed on it.

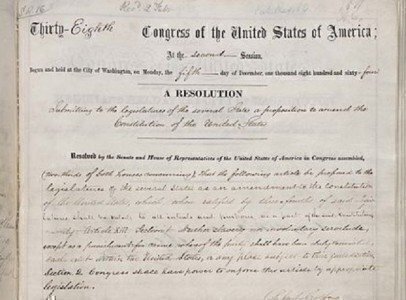

Instead, the debate between historians and conspiracy buffs is about an amendment that was almost ratified in 1812 that would have been the 13th Amendment, bumping back the current 13th Amendment--which was ratified on this day in 1865 and abolished slavery--to the position of the 14th Amendment.

Writer Jerry Adler’s 2010 explanation of the “Thirteenthers” controversy is pretty detailed and covers both sides of the issue—which isn’t new but got a big burst of publicity thanks to the Iowa GOP’s 2010 platform.

The Iowa Republicans didn’t want the current 13th Amendment banned; they just wanted the “original” one reintroduced for approval. That "missing" proposal was called the “Titles of Nobility Amendment” (or TONA). It sought to ban any American citizen from receiving any foreign title of nobility or receiving foreign favors, such as a pension, without congressional approval. The penalty was loss of citizenship.

It was an extension of Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution, which doesn’t allow a public office holder to receive a foreign title or similar honors without the consent of Congress.

Today, the idea of a constitutional controversy about the royals may seem kind of silly, but in 1812, the United States was fighting the British and had a rocky relationship with France. The fear of both nations using noble titles as bribes, along with pensions from a foreign government, was persistent. And both the Senate and the House easily passed the TONA and passed it on to the states. By late 1812, a total of 12 states had approved the 13th Amendment and ironically, it needed a 13th state to become ratified. As the War of 1812 escalated, the TONA faded away as an issue and was never ratified.

Or so we think.

In the 1980s, Adler says a researcher started finding copies of the Constitution from the pre-Civil War era that had TONA listed as the 13th Amendment. The premise was that Virginia’s legislature had approved the amendment in 1819, but somehow, it was never listed as accepted by the federal government. Further research revealed that President James Monroe asked his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, to confirm that the TONA was never ratified, which he did.

A law journal article from 1999 by Jol A. Silversmith, an attorney, explains how the TONA appeared in widely published versions of the Constitution for more than 30 years, including the official United States Statutes at Large (an official compilation of laws published by the government in 1815). His well-documented article of the “missing” amendment has more than 200 footnotes and a lot of interesting stories about how the Founding Fathers couldn’t keep track of new amendments they had just passed.

As the story goes, the editor of the 1815 book of statutes, John Colvin, couldn’t determine if the TONA amendment has been ratified, so he included it in the book with an explanatory note. Then, an official version of the Constitution was given to Congressional members that included the TONA as the 13th Amendment, as an apparent misprint. That triggered a request for Monroe and Adams to verify that the amendment hadn’t been ratified. The United States Statutes at Large wasn’t reprinted until 1845, so the mistake became part of textbooks, state publications, and newspapers, Silversmith said, for decades.

So a whole generation of Americans lived during a time when the “phantom” 13th Amendment existed, in some publications. (And with any kind of luck, you can probably find a TONA version of the Constitution at a flea market.) Silversmith also said Virginia's Senate rejected the TONA on February 14, 1811, based upon information in its records. But an official letter or note from the Virginia legislature couldn't be found several years later.

But how could the Founding Fathers and their heirs become so confused by a handful of amendments? President John Adams waited three years to acknowledge the 11th Amendment as law, and it took Secretary of State James Madison (the "Father of the Constitution") three months to recognize the 12th Amendment as an effective law.

Part of the issue was the lack of a process for states to communicate to the federal government that they had voted in favor of an amendment. Also, the number of states kept changing, which added more confusion to the ratification process.

Today, TONA supporters have made several legal challenges to get the “original” 13th Amendment recognized. The issue hasn’t been taken up by the Supreme Court, and Silversmith wrote that a 2005 U.S. district court ruling said that based on Article V of the Constitution, the inclusion of TONA in published documents doesn’t make it an amendment.

That hasn’t kept the debate over TONA off the Internet, as there are many websites that claim it is the legitimate 13th Amendment. And there is no expiration date for the TONA amendment, which means that it can be introduced to 35 more states that didn’t vote on it originally.

It may seem that preposterous that an amendment from the early 1800s could still become a law today, but the 27th Amendment was proposed in 1789 and finally approved in 1992.

Scott Bomboy is the editor-in-chief of the National Constitution Center.