The majority of the special District Court in Madison ruled that the Assembly election maps will “entrench” the GOP’s control of the legislative body throughout the years until the next Census is taken in 2020, when a new plan likely will be necessary. The majority strung together a series of comments over the years by Supreme Court Justices to construct the theory of party “entrenchment:” as a constitutional violation.

The majority of the special District Court in Madison ruled that the Assembly election maps will “entrench” the GOP’s control of the legislative body throughout the years until the next Census is taken in 2020, when a new plan likely will be necessary. The majority strung together a series of comments over the years by Supreme Court Justices to construct the theory of party “entrenchment:” as a constitutional violation.

Because the new districts will effectively keep Democrats in a minority status in the Assembly for the rest of the decade, the ruling said, Democratic voters will be deprived of their opportunity to elect legislators of their choice, to represent their interests, in violation of their constitutional right to join with voters of like political sentiments — under the First Amendment — and to legal equality — under the Fourteenth Amendment.

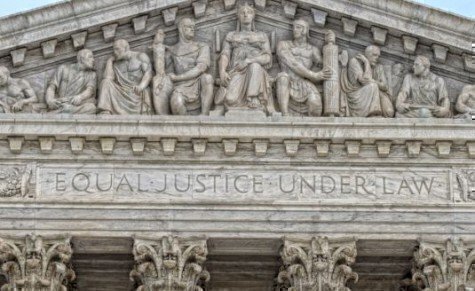

Under current federal law, special three-judge District Courts are assembled to decide redistricting challenges, and appeals from those courts’ decision go directly to the Supreme Court rather than first to a federal appeals court. Wisconsin Attorney General Brad D. Schimel said on Monday that the state will appeal. The case probably will reach the Court for action after there is a ninth Justice to fill the existing vacancy on the bench.

The Supreme Court from time to time has shown some interest in the question of when too much partisanship has gone into drawing up new election maps, but it has never found a formula for answering that question. The Wisconsin ruling is the first to accept an answer suggested by lawyers and political experts.

The dissenting judge argued that the redistricting process is inherently one for the politicians, not the courts, but that the new ruling is likely to force states to take away from their legislatures the duty to engage in redistricting, handing the task to non-partisan commissions.

The ruling emerged in 159 pages — 117 pages of writing, plus two pages of charts, for the majority, and 40 for the dissent. Senior Circuit Judge Kenneth F. Ripple, who normally sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, wrote for the majority, joined by Senior District Judge Barbara B. Crabb of Madison. Dissenting was Chief Judge William C. Griesbach of Green Bay. (Three judge federal trial courts usually have a Circuit judge and two District judges.)

In a series of decisions dating back to 1973, the Supreme Court has been faced with claims that redistricting has grown so deeply partisan that it leads to one-party domination, creating a constitutional problem in equal representation. But, as the Wisconsin court noted Monday, there is no single opinion among those decisions that has attracted a majority of Justices.

Some Justices have argued that the courts simply have no business judging the partisan nature of the redistricting process. Others have argued that partisan gerrymandering can be unconstitutional, but no majority has ever assembled around a “manageable” standard.

The Wisconsin case, along with a case now moving along in a three-judge District Court in Baltimore, involving Maryland’s congressional redistricting, are being closely watched because those involve attempts to frame a constitutional formula.

In both cases, the suggested formula by the challengers to new districting was to compare the districts drawn for election of the disfavored party’s candidates with those drawn for the favored party’s candidates, to see how big an advantage the overall map gives to the favored party. The difference results because, in the disfavored districts, that party’s followers were either loaded into fewer districts to minimize their share statewide, or were scattered among districts dominated by the other party’s voters to neutralize their power.

If the two parties’ shares of election outcomes compare one-to-one, there is no partisan gerrymandering. But the larger the difference, distributing population to give the favored party’s voters more electoral power — that is, in a partisan gerrymander.

The majority in the Wisconsin court did not base its ruling directly on that formula, although it did say that using that formula tends to bolster its main conclusion that there was, in fact and in law, a partisan gerrymander for Assembly seats under the 2011 Wisconsin map.

The majority summarized its standard for judging partisanship as a three-step approach.

First, a court looks at evidence of what the legislative sponsors of the maps intended, to see if there was a specific aim “to place a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation” — that is, the disfavored party’s voters.

Second, the court judges whether the resulting maps did have that effect on the disfavored party’s followers. And, finally, the court decides whether that effect can be justified on the basis of some “legitimate legislative grounds.”

In the end, the majority found that the 2011 Assembly maps failed at all three steps. The most important step, it appeared, was the first: the legislative leaders’ intent. That step is proven, the decision concluded, with evidence that the lawmakers managing the redistricting process had a specific intent to “entrench [their] political party in power,” which insulates that party and its followers in the legislature from having to be concerned about the interests of citizens of the “out” party.

The majority said: “Whatever gray may span the areas between acceptable and excessive [partisanship], an intent to entrench a political party in power signals an excessive injection of politics into the redistricting process that impinges on the representational rights of those associated with the party out of power.”

The court examined the outcome of the use of the 2011 plan in the 2012 and 2014 elections, and found that the Republican leaders got just what they had sought. In 2012, the GOP’s candidates statewide drew 48.6 percent of the overall vote, but they won 60 of the 99 seats. In 2014, drawing 52 percent of the statewide vote, they won 63 of the 99 seats.

Whether Wisconsin is becoming a more Republican-oriented state, which the legislative leaders had argued, the majority said that the 2011 maps have assured that the Democrats will be held to a minority in the Assembly through this decade.

In dissent, Judge Griesbach argued that there can never be a partisan gerrymander unless the legislature, in drawing new maps, creates oddly shaped districts that violate the traditional principles of having compact, contiguous districts that respect political boundaries and zones of political interest. The 2011 map, he argued, was true to all of those principles, so that should be the end of any oversight by a court.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston is Constitution Daily’s Supreme Court correspondent. Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and he has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com, where this story first appeared.