On Monday, a divided Supreme Court said a court in a Louisiana murder case couldn’t accept a lawyer’s admission of his own client’s guilt over his client’s objections.

In McCoy v. Louisiana, the Court considered a basic question about the proper role of attorneys in murder cases. Robert McCoy originally filed his own appeal directly to the Supreme Court about two questions related to his conviction on three murder charges. McCoy was sentenced to death in the case.

In McCoy v. Louisiana, the Court considered a basic question about the proper role of attorneys in murder cases. Robert McCoy originally filed his own appeal directly to the Supreme Court about two questions related to his conviction on three murder charges. McCoy was sentenced to death in the case.

McCoy was accused of killing three people in 2008 in a dispute with his then-wife and he was arrested after fleeing to Idaho. McCoy clashed with public defenders, briefly represented himself, and then hired an attorney, Larry English, to argue his case.

The client and his attorney disagreed about McCoy’s defense strategy, and English told the court he had doubts about McCoy’s competency due to “severe mental and emotional issues. During trial, English introduced a defense that conceded McCoy’s role in the killings as a tactic to avoid the death penalty, by stressing McCoy’s mental condition. Under testimony, McCoy insisted he wasn’t guilty and he was the victim of a conspiracy. The jury found McCoy guilty of three first-degree murder counts. The jury then recommended the death penalty.

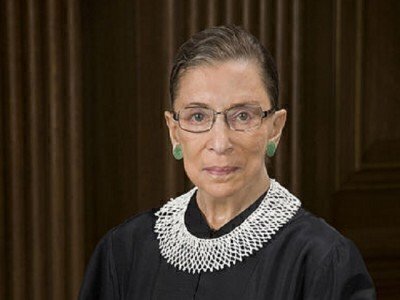

In the 6-3 decision, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said that the trial court should not have accepted English’s concession of guilt for his client.

“Larry English was placed in a difficult position; he had an unruly client and faced a strong government case. He reasonably thought the objective of his representation should be avoidance of the death penalty,” Ginsburg said. “But McCoy insistently maintained: ‘I did not murder my family.’ Once he communicated that to court and counsel, strenuously objecting to English’s proposed strategy, a concession of guilt should have been off the table.”

“The trial court’s allowance of English’s admission of McCoy’s guilt despite McCoy’s insistent objections was incompatible with the Sixth Amendment. Because the error was structural, a new trial is the required corrective,” Ginsburg said.

“With individual liberty—and, in capital cases, life—at stake, it is the defendant’s prerogative, not counsel’s, to decide on the objective of his defense: to admit guilt in the hope of gaining mercy at the sentencing stage, or to maintain his innocence, leaving it to the State to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” Ginsburg concluded.

The Louisiana Supreme Court had upheld the convictions and disagreed that the trial process violated McCoy’s rights to counsel and self-representation under the Sixth amendment. It found that English acted ethically under the conditions of the trial, citing Florida v. Nixon, a 2004 Supreme Court decision.

“In the case now before us, in contrast to Nixon, the defendant vociferously insisted that he did not engage in the charged acts and adamantly objected to any admission of guilt,” Ginsburg said. “We hold that a defendant has the right to insist that counsel refrain from admitting guilt, even when counsel’s experienced-based view is that confessing guilt offers the defendant the best chance to avoid the death penalty.”

In his dissent, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, said that the Supreme Could should not have decided the case since English didn’t really admit McCoy’s guilt in trial court.

“The Constitution gives us the authority to decide real cases and controversies; we do not have the right to simplify or otherwise change the facts of a case in order to make our work easier or to achieve a desired result,” Alito said.

“Faced with overwhelming evidence that petitioner shot and killed the three victims, English admitted that petitioner committed one element of that offense, i.e., that he killed the victims. But English strenuously argued that petitioner was not guilty of first-degree murder because he lacked the intent (the mens rea) required for the offense,” Alito said.

Among those submitting briefs supporting McCoy was The Criminal Bar Association Of England & Wales, which agreed with McCoy’s objections on originalist grounds rooted in English law. “It is the defendant, not his counsel, who selects his defense, and counsel is duty-bound to carry it through,” it claims.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.