Another monster merger is in the works: AT&T has agreed to buy Time Warner for $85 billion. The deal combines the second-largest mobile phone company with the company that owns HBO, CNN and Warner Brothers Studios, among other content assets. It is a deal that has the potential, though unlikely, to make hit shows such as Game of Thrones and Veep exclusive to DirecTV customers, which was bought by AT&T last year. The deal could have major implications for the television market and for consumers as a whole.

A deal of this magnitude was always sure to draw Washington’s attention. Indeed, President-elect Donald Trump immediately opposed it while on the campaign trail, saying, “We’ll look at breaking this up. This is too much power in the hands of too few.” Former Democratic contender Bernie Sanders struck a similar tone when he remarked, “This proposed merger is just the latest effort to shrink our media landscape, stifle competition and diversity of content, and provide consumers with less while charging them more.” Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton took a less forceful stance, saying, “I am going to follow it closely, and obviously if I am fortunate enough to be president, I will expect the government to conduct a very thorough analysis before making a decision.” Needless to say, this is far from a done deal.

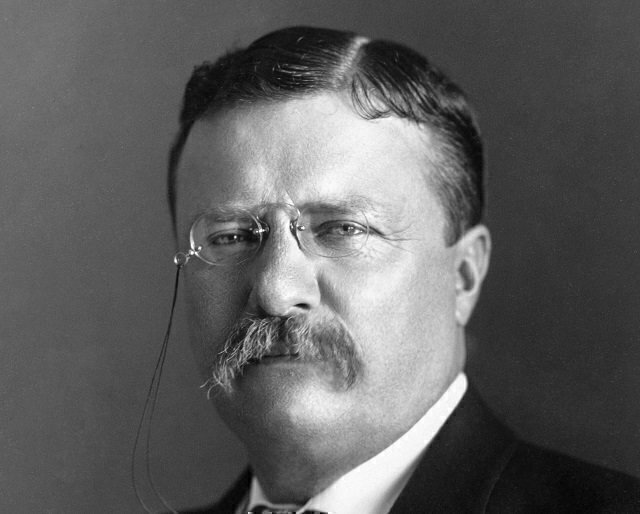

But why should the government even have an opinion on this? How did the government gain the ability to review and ultimately approve or reject big mergers like this? The answer dates back to the presidency of Theodore “the Trust Buster” Roosevelt.

Back in the late 1800s, competition was seen as a foreign concept in the business world. Monopolies and trusts began forming in industries such as steel, oil, rail roads and many others. This meant high prices and little innovation. And even laws such as the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was supposed to outlaw any form of monopolization, were not enforced enough to protect the average consumer. That is where Roosevelt comes in.

His presidency began with a strike against JP Morgan, the head of the Northern Securities Company, a railroad trust. Despite outcries from the business community, his lawsuit, which sought to dismantle the NSC, was upheld by the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision. He would later join forces with future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis to break up the New Haven Railroad Company merger with the Boston and Maine Railroad, again defeating Morgan.

Roosevelt then turned his focus to John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil. He ordered his Attorney General, Philander Knox, to file a suit to break up Standard Oil on the basis that the company had engaged in purposely deceitful tactics to raise prices for consumers and competing interests, in order to maintain its hold on the market. The Supreme Court ruled once again in favor of the government, but not until 1911. As a result, the trust was broken into 33 different companies. Overall, the Trust Buster would bring up 54 antitrust suits while in office.

Roosevelt and his successors were aided in their endeavors by the Sherman Act as well as two others that were enacted in 1914: the Federal Trade Commission Act, which created the Federal Trade Commission, allowing for congressional oversight and reinforcing the Sherman Act; and the Clayton Act, which focuses on mergers and interlocking directorates (one person making decisions for competing companies). It is this Act that may cause the proposed AT&T and Time Warner merger to fail.

AT&T previously ran into problems with the Clayton Act when they attempted to merge with T-Mobile. It was rejected on the basis that the consumer would suffer if the second- and third-largest cellular companies merged. That question seemed cut and dry. Congress struck down a deal that would have effectively created a monopoly.

However, the Time Warner deal is different in that it involves two different industries. "This is not the T-Mobile deal; there is no competitor being removed from the marketplace," AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson noted during a conference call with the media. "Time Warner is a supplier to AT&T. It's a classic vertical merger. They're always dealt with by concessions and conditions—that's what we anticipate happening here."

Congress in the past has upheld deals like this one. The heavily scrutinized NBC-Comcast deal had several different provisions added to it, including a fixed price for lower-income families and discounts on laptops and desktops for them. If approved, AT&T and Time Warner may have to accept similar provisions. But with a new President, it could be a long time before a final ruling is made.

Chris Calabrese is an intern at the National Constitution Center. He is also a recent graduate of St. Joseph’s University.