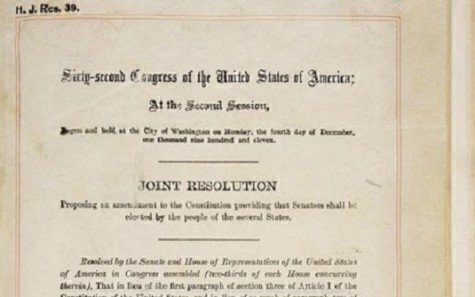

Back on this day in 1913, the 17th Amendment to the Constitution went into effect, ending indirect elections to the U.S. Senate. To this day, some folks want that amendment repealed on the theory it curtails states’ rights as envisioned by the Founders.

Prior to 1913, when the 17th Amendment was ratified, the Constitution allowed state legislatures to choose two U.S. senators to represent them in Congress. Members in each state House and each state Senate, in most cases, would meet separately to pick a candidate as its representative in the U.S. Senate.

Prior to 1913, when the 17th Amendment was ratified, the Constitution allowed state legislatures to choose two U.S. senators to represent them in Congress. Members in each state House and each state Senate, in most cases, would meet separately to pick a candidate as its representative in the U.S. Senate.

In the decades prior to the 17th Amendment’s passage, that practice was continually attacked as corrupt and problematic by reformers. But in recent years, some conservatives have demanded the right for the state legislatures to name their states’ representatives at the U.S. Senate.

In 2016, Utah’s legislature passed a resolution calling for the 17th Amendment’s appeal, quoting James Madison and Alexander Hamilton in the resolution. “Whereas, James Madison argued in Federalist Papers No. 62 that, ‘The appointment of senators by state legislatures gives the state governments such an agency in the formation of the federal government as must secure the authority of the former,’” the lawmakers wrote.

Todd Zywicki, a George Mason University law professor, explained two of the current repeal arguments to the Huffington Post.

“The framers understood that, in order for the states to be protected from federal government overreach it was necessary to give the states a formal check,” Zywicki said. “That check was by allowing the states in their corporate political capacity, the state legislatures, to choose senators.

He added that the original election system was a hedge against corruption. “The second aspect was that the Senate was to be a check on special-interest activity,” Zywicki said. “By having the Senate chosen by a different constituency than the House, that was designed to raise the level of consensus to enact legislation, making it more difficult for special interests to capture the government.”

But in the era before repeal, how the states picked their Senators and how often that process was stalemated triggered enough outrage to lead to a constitutional amendment.

Corruption was certainly an issue. In their 2013 analysis of the historical selection process, political scientists Wendy J. Schiller and Charles Stewart III noted that a lot of money was spent by candidates and factions influencing state legislators to vote their way.

“This use of large sums of cash to fund campaigns for state legislators, advertise in media outlets (or purchase them outright), and bribe state legislators once balloting began, was typical in indirect Senate elections,” said Schiller and Stewart.

However, they also concluded that modern direct Senate elections aren’t that different in terms of money and ballots. “Despite the blatant use of money to win indirect Senate elections, 100 years after the 17th Amendment was enacted, the modern Senate elections process is swamped with campaign money in ways that far outpace elections under the indirect elections system,” they said.

But a look at Senate indirect election trends between 1871 and 1913 shows one big current roadblock to a 17th Amendment repeal. In 98 percent of those indirect elections, the legislators always voted for a candidate from their own party for the Senate.

Currently, the Senate is made up of 54 Republicans, 44 Democrats and two Independents. If the Senators were appointed today by state lawmakers along party lines within the states themselves, there would be well more than 60 seats for the GOP in the current Senate.

That would put the Republicans over a filibuster-proof 60-vote majority and very close to a 67-vote supermajority needed to override a presidential veto and approve constitutional amendments for state ratification. And it also would require at least 13 Democratic Senators to approve a 17th Amendment appeal resolution that could lead to their own removal from office.

Another option would be a direct Article V convention of the states to pass a 17th Amendment repeal. That’s never been done before, but ironically it almost happened 105 years ago when enough states were fed up with the indirect Senate election process.

By 1912, many states starting using the “Oregon System,” where voters took part in primaries that committed state lawmakers to pick the primary winners as Senators. At the same time, 27 states not satisfied with the process petitioned Congress for an Article V constitutional convention. With just four more states needed for a convention and indications that three western states would join the Article V movement, the Senate finally agreed to approve the proposed 17th Amendment by a six-vote margin.

On May 31, 1913, one of the amendment’s biggest supporters, William Jennings Bryan, signed the document in his role as Secretary of State, telling Congress that it “had become valid to all intents and purposes as a part of the Constitution of the United States.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.