Philadelphia has a rich history of hosting colorful political conventions, and in the first of a series of articles, we look at the controversial conventions of the slavery and anti-immigrant era before the Civil War.

This July, Philadelphia will host its 13th major national political convention when the Democrats convene at the Wells Fargo Center in South Philadelphia. Seven of the conventions held in Philadelphia in the past were for the Republicans, while another four were for Democrats, with the Whigs and Progressives also meeting in Philadelphia.

This July, Philadelphia will host its 13th major national political convention when the Democrats convene at the Wells Fargo Center in South Philadelphia. Seven of the conventions held in Philadelphia in the past were for the Republicans, while another four were for Democrats, with the Whigs and Progressives also meeting in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia only trails Chicago as the most-popular convention location in American history. The Windy City, with its central location, has hosted 26 conventions. (The last Chicago national convention was in 1996.)

Baltimore also has hosted an estimated 13 major conventions (8 for the Democrats, 3 for the GOP, 2 for the Whigs), but the last time it did host a big convention was in 1912. In the early days of political conventions, starting in 1832, Baltimore hosted 11 conventions in a 28-year-period before the Civil War.

In the critical period before the war, Philadelphia also started hosting conventions, with three very different parties meeting in the city of Brotherly Love.

1848: The Whig’s high-water mark

The Whig Party was the main rival to the Democratic Party founded by Andrew Jackson from 1834 to 1856. The Whigs had four U.S. Presidents in that time period, but only two were elected: William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor. A third, John Tyler, succeeded Harrison after the President's death in 1841, but Tyler was kicked out of the Whigs while still in the White House. And Millard Fillmore was the last Whig President as the party crumbled under the pressures that led to the Civil War. Fillmore succeeded Taylor, who was the second President to die in office.

In 1848, the Whigs had their national convention at Philadelphia’s Chinese Museum, about 10 blocks south of the current convention center. Thousands of Whigs arrived in Philadelphia and about 300 held seats as convention delegates. The 1848 election front runner was an independent, the aforementioned General Zachary Taylor, who was a hero of the Mexican-American War. Taylor decided to run for the White House as a Whig, due partly to his dislike of outgoing President James K. Polk.

Taylor’s main rival in Philadelphia was the Whig party leader, Henry Clay, who had lost to Polk in the 1844 presidential election. Daniel Webster and General Winfield Scott were also contenders, but Taylor prevailed on the fourth ballot. The party named Fillmore, a moderate anti-slavery New Yorker, as Taylor’s running mate. In the end, former President Martin Van Buren, as a third-party Free Soil Party candidate, helped split the vote in New York in favor of Taylor, and Taylor narrowly defeated Lewis Cass in the general election.

1856: The Know Nothings gather in Philly

In February 1856, one of the most controversial political parties in history met at Philadelphia’s National Hall to pick its own candidate for a divided general election. In the four years since Democratic candidate Franklin Pierce took the 1852 election from Winfield Scott, the Whigs fell apart as a national party as its members took sides on the slavery issue. Some former Whigs, like William Seward and Abraham Lincoln, joined the newly formed Republican Party. But another party, the American, or Native-American Party, also attracted former Whig Party members. They become known as the “Know Nothings,” since party members wouldn't discuss their beliefs or party membership with outsiders.

The Know Nothings were an anti-immigrant nativist party. The party doctrine stood firmly against Catholics and foreigners, and its members had some regional election success in the 1850s. But the Know Nothings, like the Whigs, had split on the slavery issue. In Philadelphia, former President Fillmore won a first ballot nomination, with President Jackson’s nephew, Andrew Donelson, as his running mate. The Know Nothings did poorly in the 1856 election and soon disappeared as a political factor.

1856: The first Republican convention

At this point, the Grand Old Party was the brand new party and it gathered at Philadelphia’s Musical Fund Hall on Locust Street in June 1856 to pick its first presidential candidate. The Republicans were formed after disgruntled Whigs, anti-slavery Democrats, former Free Soil members and abolitionists came together. It was viewed as a regional party, with its strength in the northern and western states.

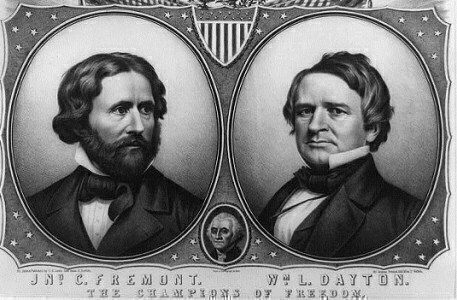

The leading Whigs of the day were future Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon Chase and, of course, William Seward. Both men dropped from presidential contention before the 1856 Philadelphia meeting. Instead, it was 71-year-old Supreme Court Justice John McLean against a 43-year-old rival, John Fremont, in the nomination fight. The dashing Fremont had gained a great deal of celebrity for his expeditions in the West, and he had briefly served in the Senate.

Fremont easily defeated McLean on the first ballot. Former New Jersey senator William Dayton was the vice presidential nominee, defeating another former Congress member, Abraham Lincoln. In the fall, the Democrats took the White House and the Electoral College when James Buchanan carried Pennsylvania, but Buchanan only took 45 percent of the popular vote. The Republicans and the Know Nothings had 55 percent of the vote combined, and the Republicans were within a two-state margin of taking the 1860 vote in the Electoral College.

Scott Bomboy is editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.