The City of Brotherly Love hosted three presidential nominating conventions in 1948, as television first affected the national meetings, which were held in sweltering heat amid controversy.

By the time that the Republicans, Democrats and the third-party Progressives were done in Philadelphia, the political landscape shifted dramatically.

The Democratic Party, in particular, seemed to be ready to split into several factions. Just four years earlier, it was united under President Franklin Roosevelt. But after Roosevelt’s death and Harry Truman’s ascendance to the presidency, the Republicans gained control of Congress and were poised to recapture the White House in 1948.

Between June 21, 1948, when the GOP convention started at Philadelphia’s Municipal Center and Convention Hall, and July 25, 1948, the last night of the Progressive Party convention at Shibe Park, the traditional two-party presidential race had become a four-party affair, with three factions containing Democrats.

Philadelphia’s leaders paid $250,000 to the Democrats and the Republicans to locate their conventions in the city. In addition to the financial benefit, Philadelphia happened to be a mid-way location of a new coaxial television network that would bring convention television coverage to a large audience for the first time. As many as 10 million people on the East Coast would get their first look at a convention, after radio dominated such coverage since 1924.

The city faced two problems that affected visiting delegates and the TV folks. First, the city and the region lacked adequate hotel space. But the bigger problem was a heat wave that broiled the city for three months. A decade earlier Philadelphia decided to not install modern air conditioning in Convention Hall as a cost-saving measure; the presence of television lights inside the hall only compounded the problem.

The television crews, the delegates and the candidates battled the oppressive conditions for weeks. Edward R. Murrow, the star radio correspondent for CBS, was begged by corporate management to take part in television coverage. Once in Philadelphia, Murrow was soaked in sweat as he was forced to carry a primitive TV backpack on the convention floor. The networks also agreed to share the use of five fixed-position cameras in the convention hall - with one shared director.

The Republican convention started without a preordained candidate. As in 1940 and 1944, New York Governor Thomas Dewey was the Republican convention favorite. Dewey won the nomination in 1944 when Ohio’s Robert Taft didn’t run against him. However, in 1948, Dewey faced opposition from Taft, Harold Stassen, Arthur Vandenberg and Earl Warren.

Dewey was able to lock up the nomination on the third ballot, after the anti-Dewey coalition couldn’t agree on a compromise ticket. Television added a new dimension as live coverage showed delegations on the floor switching their votes to Dewey. The nominee then picked Warren, the popular California governor, as his running mate, forming a potential Dream Ticket for the Republicans.

On July 12, the Democrats started their convention in the same location where the Republicans met, but under hotter conditions physically and politically. Truman was not expected to win re-election, but he was the presumptive candidate, unless former General Dwight D. Eisenhower could be convinced to run against Truman at the convention. Local TV station WCAU-TV was with Senator Claude Pepper when he received a telegram from Eisenhower, officially declining any nomination.

With Truman’s nomination assured, the delegates then had to vote on a contentious civil rights plank. A young Senate candidate from Minnesota, Hubert Humphrey, gave an impassioned eight-minute speech demanding that Democrats support expansive rights. “The time is now arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights,” Humphrey pleaded.

The delegates narrowly approved the civil rights plank, and then two Southern delegations promptly left the convention floor protesting the vote. On live television and radio, the delegates threw their credentials on the floor.

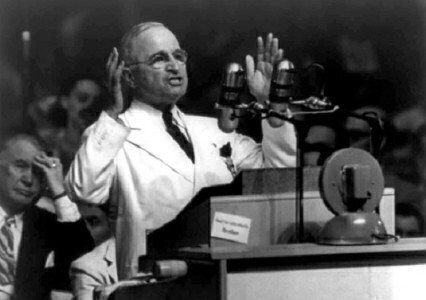

Truman tried to rally the convention during his acceptance speech. “The battle lines of 1948 are the same as they were in 1932," Truman said, comparing his plight to that of a President Roosevelt who faced problems caused by GOP lawmakers.

But on July 17, the southern delegates met in Birmingham, Alabama, to form the States’ Rights Democratic Party, known popularly as the Dixiecrats. The convention named South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond as its presidential nominee, and its goal was to win enough electoral votes to force the House of Representatives to decide the election. “We stand for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race,” its party platform read.

Finally on July 23, 1948, the liberal Progressive Party, which included dissatisfied Democrats, held its own convention at Philadelphia’s Municipal Auditorium and the Shibe Park baseball stadium.

Henry Wallace, the former Roosevelt Vice President who Truman had replaced on the 1944 ticket, left the Democrats in 1946 and by 1947 he was the assumed presidential candidate of the Progressives. The party was against Truman’s Cold War foreign policy and it supported civil rights in its platform. It also had the endorsement of the American Communist Party. Wallace spoke to a crowd of 32,000 supporters outside at the stadium on July 25.

“The future belongs to those who go down the line unswervingly for the liberal principles of both political democracy and economic democracy regardless of race, color or religion,” he said. The Progressive Party convention was heavily attended, with a healthy number of FBI agents in the audience.

In the end, Truman used a grassroots campaign and unending attacks on the GOP-controlled Congress to defeat Dewey in the most famous of all presidential upsets. The Dixiecrats won four states and 39 electoral votes. The Progressives had the same popular vote as the Dixiecrats but no electoral votes, and both parties soon faded away.

The biggest winner in Philadelphia that summer may have been the nascent television industry. It had overcome logistics and the heat to pull off extensive high-interest political coverage. By 1952, television coverage was national for the Democratic and Republicans at their conventions, with an estimated 70 million viewers.