In the first day of the Senate Impeachment trial of President Donald J. Trump, contentious debate over the rules of the trial went deep into the night. After a heated exchange between House Manager Jerry Nadler and the President’s lawyers, Chief Justice John Roberts admonished both sides.

"In the 1905 Swayne trial, a senator objected when one of the managers used the word 'pettifogging' and the presiding officer said the word ought not to have been used," Roberts said. "I don't think we need to aspire to that high of a standard, but I do think those addressing the Senate should remember where they are."

In so doing, he made a reference to the 1905 impeachment trial of Charles Swayne, when a House manager was criticized for using the phrase “pettifogging.” “I don’t think we need to aspire to that high of standard, but I do think those addressing the Senate should remember where they are,” Roberts said.

This naturally brings about two questions: what is “pettifogging” and what exactly happened in 1905 in the trial of Judge Swayne?

This naturally brings about two questions: what is “pettifogging” and what exactly happened in 1905 in the trial of Judge Swayne?

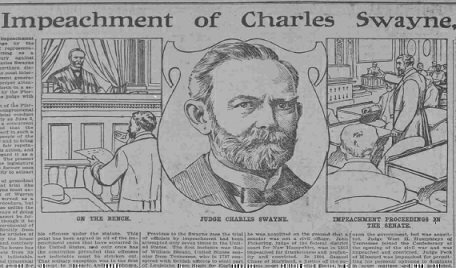

Charles Swayne was a United States District Judge for the Northern District of Florida. He was impeached on December 13, 1904 by the House of Representatives. Swayne was accused of filing false travel vouchers, improper use of private railroad cars, unlawfully imprisoning two attorneys for contempt, and living outside of his district. Swayne’s trial lasted two and a half months before he was acquitted by the Senate on February 27, 1905 on all 12 articles of impeachment. Although it was broadly accepted that Swayne was guilty of the corrupt conduct, the Senate declined to find Swayne guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

During the trial of Swayne, Alabama Senator Edmund Pettus, the former Confederate General, objected to the use of the word, which the Presiding Officer, Senator Orville Platt of Connecticut, agreed with. Swayne’s lawyer, Mr. Thurston, objected to the use of statements made by Swayne while a witness before a committee of the House of Representatives as hearsay, saying it was a strategy of “indirection” and “pettifogging.” Republican House Manager Henry Wilbur Palmer of Pennsylvania responded that the testimony was offered in good faith and was not “pettifogging,” as it was a voluntary statement and competent testimony.

“Pettifogging” is a term that dates back to the nineteenth-century and refers to trickery and avarice. It had a variety of usages, particularly in the political and legal context, but generally suggested immoral, deceitful behavior unbecoming of the office or position. Going back to 1838, the New York Times, reporting on the actions of Attorney General Butler’s objections to a currency bill to repeal the specie circular of President Andrew Jackson, had “put forth the miserable pettifogging document which has been given to the world to break the torrent of public indignation which was expected to fall upon the head of the author of this deliberate outrage upon the Constitution of the land and liberties of the people.” It was a term of derision for a subservient, profligate, undignified and faithless actor.

During a period in which “free labor” ideology was growing, “pettifogging” could also refer to dishonest labor or living, particularly lawyers who abused the meaning of the law and did not stand for the enlightened Republic and the Constitution. As a North Carolina paper put it, a bad lawyer was a “pettifogger or seventh-rate county court lawyer—degrading himself and the dignified station he occupies by practicing little trickery for mean, selfish party purposes.” This was a lawyer who was clever and cluttered up procedure only for the purpose of making money, not in pursuit of justice. Politicians, too, were targets. In 1856, the New York Herald referred to pettifogging as the “art of pettifogging and elaborate diplomate verbiage.” In reference to the “the actions of the Pierce administration “cringing to foreign opinions on the one side, to domestic political feuds on the other.”

By the turn of the century, the term remained a reference to avaricious, partisan or undignified chicanery. Webster’s defined it in 1890 as “pursuing gain by mean practices” and a pettifogger as a “peddler or huckster.” Politicians and corrupt foreign nations were routinely described as engaging in “pettifogging schemes.” President Woodrow Wilson himself was assailed in the press as a pettifogger. Chicago’s Daybook covered President Wilson’s re-election victory by suggesting he only won because he “went before the people with the old-time nefarious legal manners of browbeating and pettifogging, trying to befuddle and confuse the public mind with sophistical film-flamming, three-card monte game of the ancient legal political gambler. People have a natural aversion against being swindled, and in this instance, kept out of the clutches of the flim-flammers.” Even during World War I, papers referred constantly to the “pettifogging” of the Germans when discussing the “freedom of the seas” while they were practicing a strategy of unrestricted warfare against allied vessels.

The history of the word and its use during the 1905 trial of Charles Swayne show Chief Justice Roberts employed the word as a means to call for civility, even if many members of the Senate may not have understood its origins and meaning.

Nicholas Mosvick is a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.